Software-defined far memory in warehouse-scale computers Lagar-Cavilla et al., ASPLOS’19

Memory (DRAM) remains comparatively expensive, while in-memory computing demands are growing rapidly. This makes memory a critical factor in the total cost of ownership (TCO) of large compute clusters, or as Google like to call them “Warehouse-scale computers (WSCs).”

This paper describes a “far memory” system that has been in production deployment at Google since 2016. Far memory sits in-between DRAM and flash and colder in-memory data can be migrated to it:

Our software-defined far memory is significantly cheaper (67% or higher memory cost reduction) at relatively good access speeds (6µs) and allows us to store a significant fraction of infrequently accessed data (on average, 20%), translating to significant TCO savings at warehouse scale.

With a far memory tier in place operators can choose between packing more jobs onto each machine, or reducing the DRAM capacity, both of which lead to TCO reductions. Google were able to bring about a 4-5% reduction in memory TCO (worth millions of dollars!) while having negligible impact on applications.

In introducing far memory Google faced a number of challenges: workloads are very diverse and change all the time, both in job mixes and in utilisation (including diurnal patterns), and there is near zero tolerance for application slowdown. If extra provisioned capacity was needed to offset a slowdown for example then this could easily offset all potential TCO savings. This boils down to a single digit µs latency toleration in the tail for far memory, and in addition to security and privacy concerns, rules out remote memory solutions. Google’s “far” memory it turns out is exactly the same memory, but with compressed data stored in it!

The opportunity

One of the very earliest question to be addressed is how to define ‘cold’ memory, and given that, how much opportunity there is for moving cold memory into a far memory store.

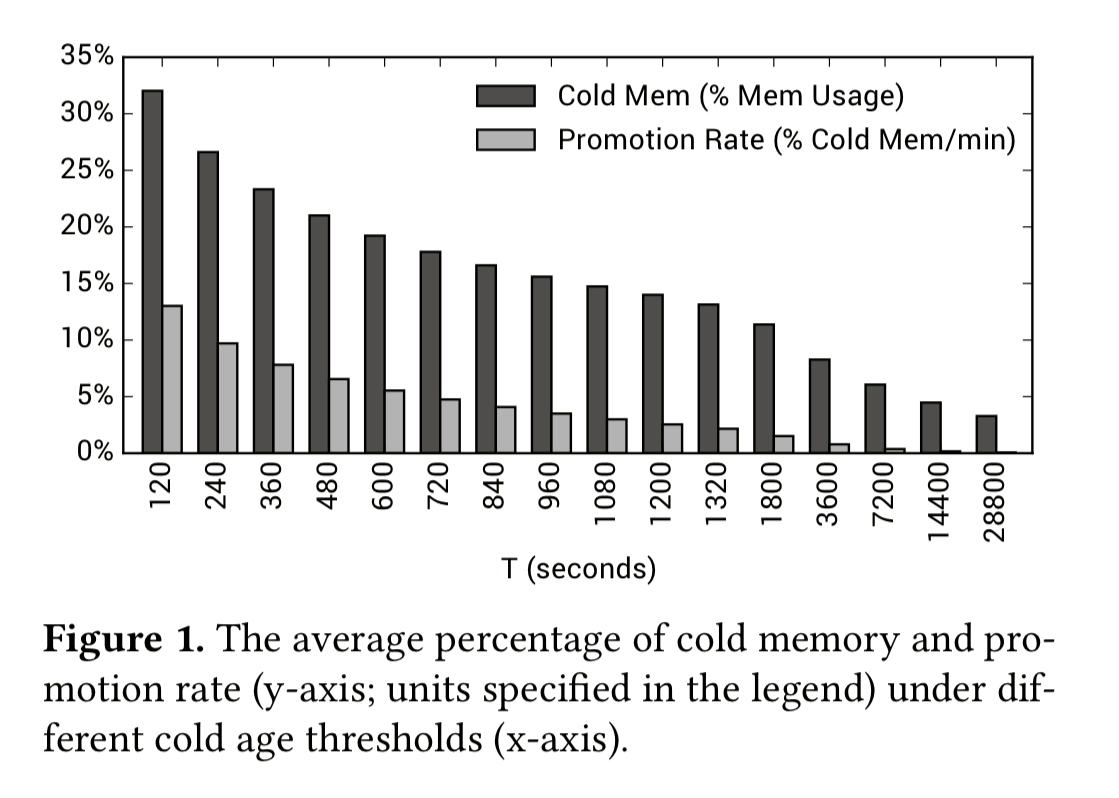

We focus on a definition that draws from the following two principles: (1) the value of temporal locality, by classifying as cold a memory page that has not been accessed beyond a threshold of T seconds; (2) a proxy for the application effect of far memory, by measuring the rate of accesses to cold memory pages, called promotion rate.

With T set at 120 seconds, 32% of the memory usage in a Google WSC is cold on average. At this threshold applications access 15% of their total cold memory on average every minute.

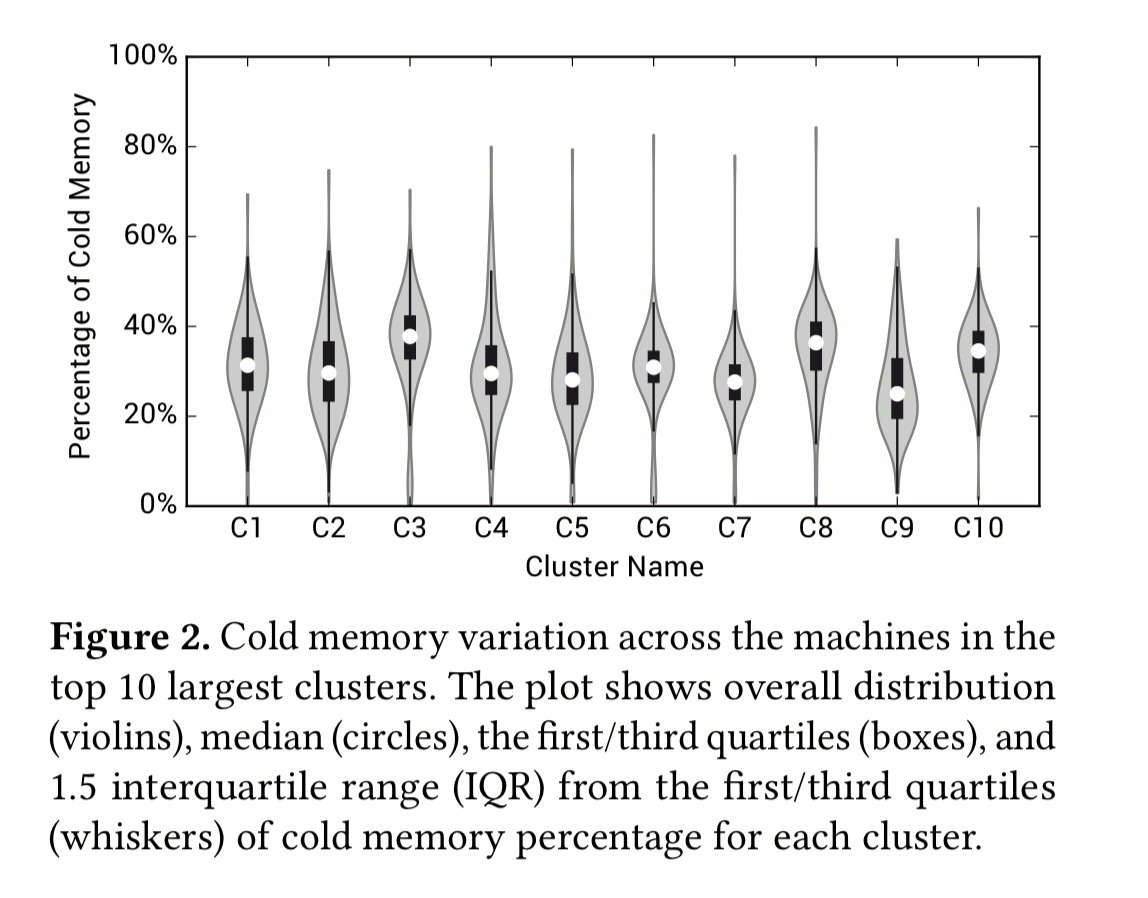

Across individual machines in a cluster, the percentage of cold memory varies for 1% to 52%.

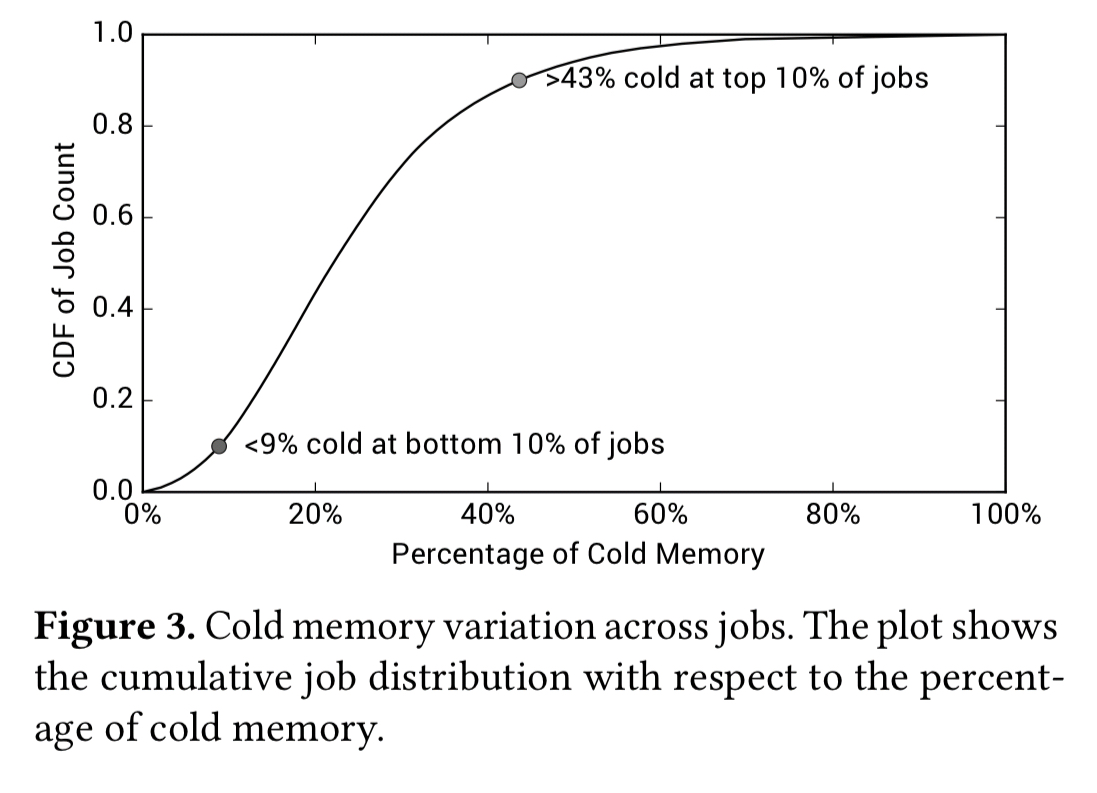

It also varies across jobs:

…storing cold memory to cheaper but slower far memory has great potential of saving TCO in WSCs. But for this to be realized in a practical manner, the system has to (1) be able to accurately control its aggressiveness to minimize the impact on application performance, and (2) be resilient to the variation of cold memory behavior across different machines,clusters, and jobs.

Enter zswap!

Google use zswap to implement their far memory tier. Zswap is readily available and runs as a swap device in the Linux kernel. Memory pages moved to zswap are compressed (but the compressed pages stay in memory). Thus we’re fundamentally trading (de)-compression latency at access time for the ability to pack more data in memory. Using zswap means that no new hardware solutions are required, enabling rapid deployment across clusters.

…quick deployment of a readily available technology and harvesting its benefits for a longer period of time is more economical than waiting for a few years to deploy newer platforms promising potentially bigger TCO savings.

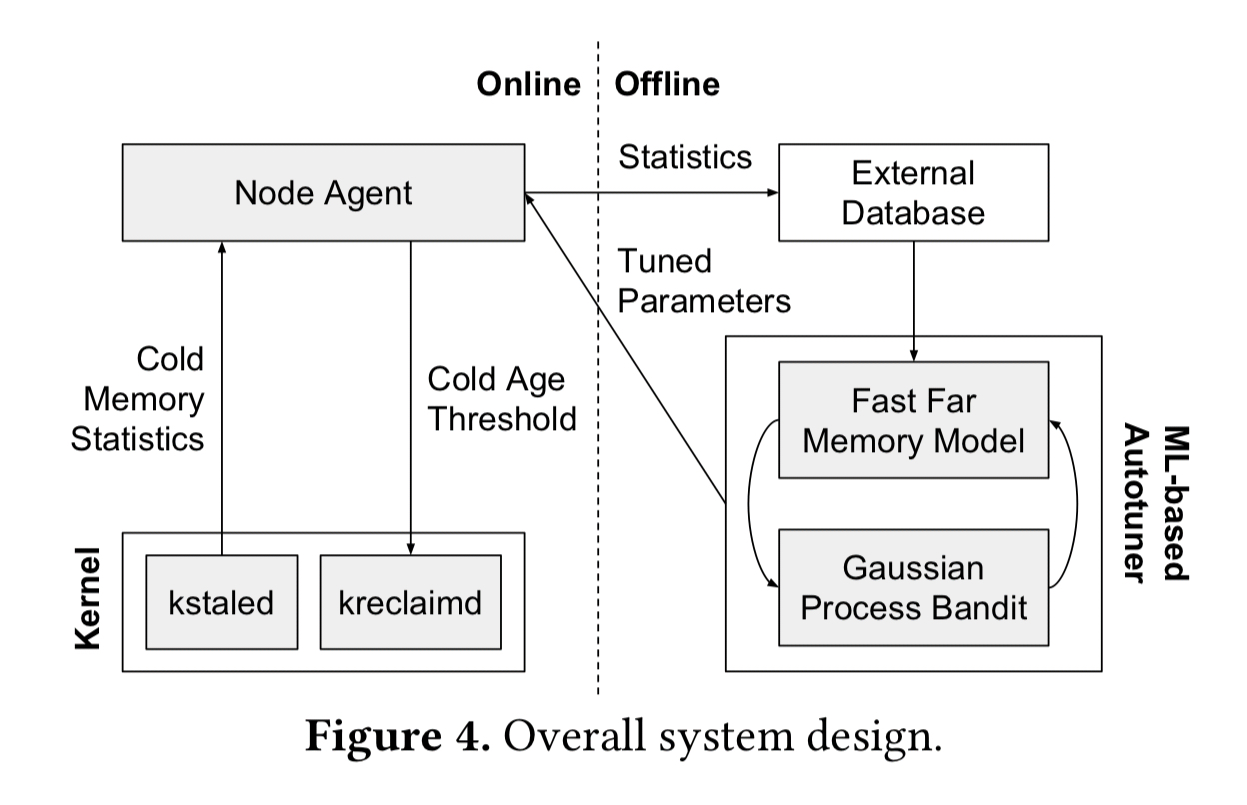

zswap’s default control plane did not meet Googles strict performance slowdown and CPU overhead budgets though, so they built a new one to identify cold pages and proactively migrate them to far memory while treating performance as a first-class constraint. Cold memory pages are identified in the background and proactively compressed. Once accessed, a decompressed page stays in that state until it becomes cold again.

The key to an efficient system is the identification of cold pages: the cold age threshold determines how many seconds we can go without a page being accessed before it is declared cold. The objective is to find the lowest cold age threshold that still allows the system to satisfy its performance constraints. A good proxy metric for the overhead introduce by the system is the promotion rate: the rate of swapping pages from far memory to near memory. For a given promotion rate, large jobs with more total memory are likely to see less of a slowdown than smaller jobs…

… therefore we design our system to keep the promotion rate below P% of the application’s working set size per minute, which serves as a Service Level Objective for far memory performance.

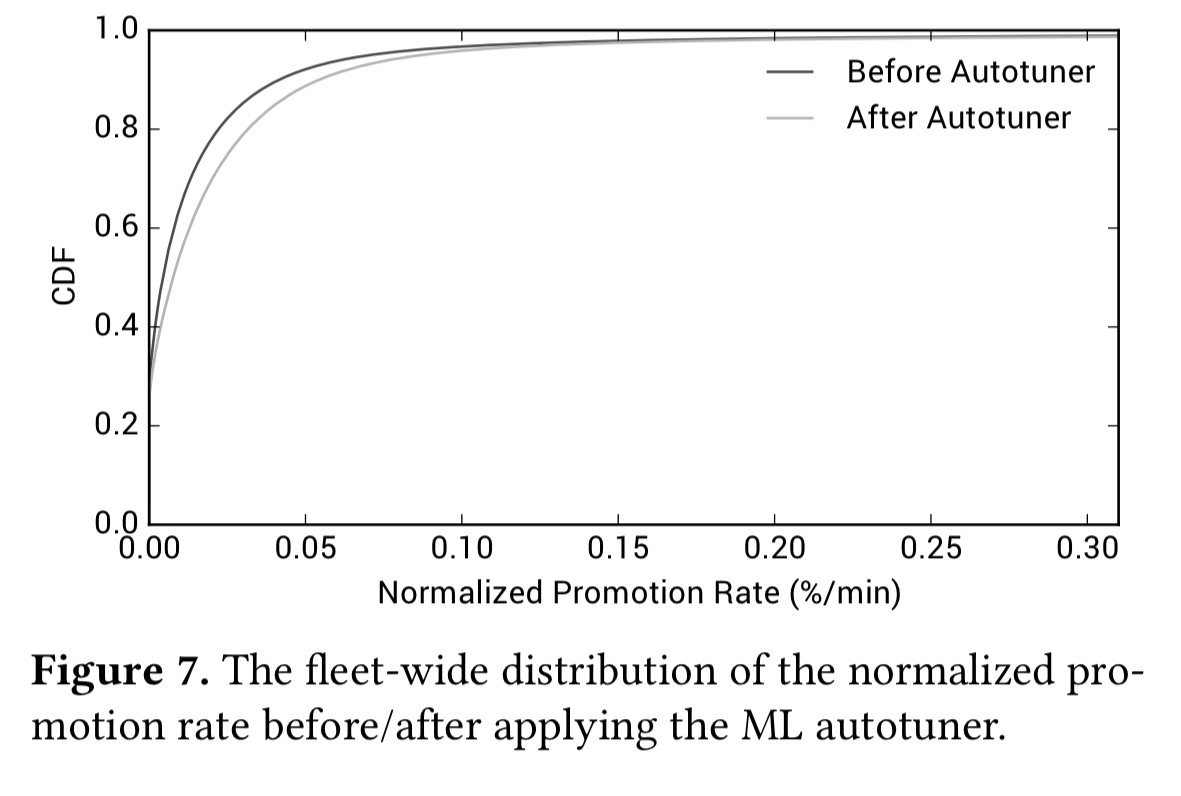

From extensive A/B testing, P was empirically determined to be 0.2%/minute. At this level the compression/decompression overhead does not interfere with other colocated jobs on the same machine.

What cold age threshold results in at 0.2%/min promotion rate though? Google maintain a promotion histogram for each job in the kernel, which records the total promotion rate of pages colder than the threshold T. This gives an indication of past performance, but we also want to be responsive to spikes. So the overall threshold is managed as follows:

- The best cold age threshold is tracked for each 1 minute period, and the K-th percentile is used as the threshold for the next one (so we’ll violate approximately 100-K% of the times under steady state conditions)

- If jobs access more cold memory during the minute than the chosen K-th percentile then the best cold age threshold from the previous minute is used instead

Zswap is disabled for the first S seconds of job execution to avoid making decisions based on insufficient information.

The system also collects per-job cold-page histograms for a given set of predefined cold age thresholds. These are used to perform offline analysis for potential memory savings under different cold-age thresholds.

ML-based auto-tuning

To find optimal values for K and S, Google built a model for offline what-if explorations based on collected far-memory traces, that can model one week of an entire WSCs far memory behaviour in less than an hour. This model is used by a Gaussian Process (GP) Bandit machine learning model to guide the parameter search towards an optimal point with a minimal number of trials. The best parameter configuration found by this process is periodically deployed to the WSC with a carefully monitored phased rollout.

The big advantage of the ML based approach is that it can continuously adapt to changes in the workload and WSC configuration without needing constant manual tuning.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first use of a GP Bandit for optimizing a WSC.

Evaluation

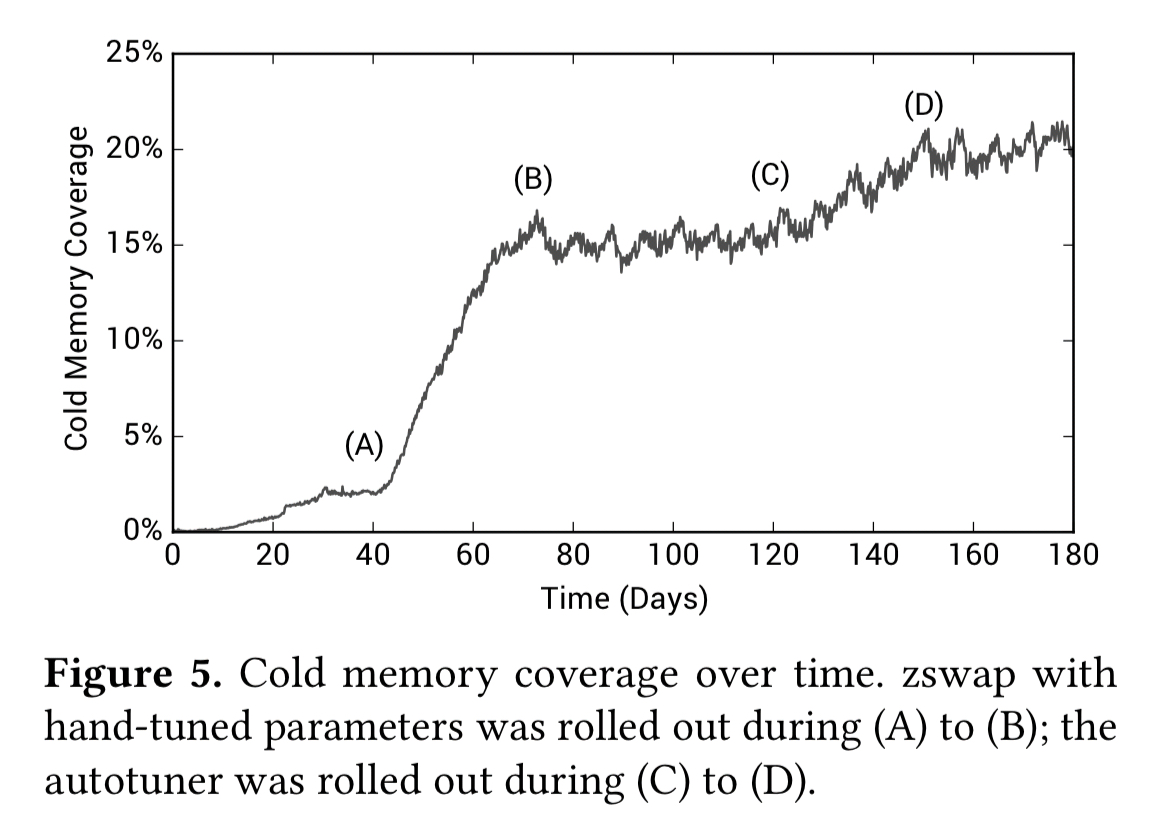

The far memory system has been deployed in production since 2016. The following chart shows the change in cold memory coverage over that time, including the introduction of the autotuner which gave an additional 20% boost.

Cold memory coverage varies over machine and time, but at the cluster level it remains stable. This enabled Google to convert zswap’s cold memory coverage into lower memory provisioning, achieving a 4-5% reduction in DRAM CTO. “These savings are realized with no difference in performance SLIs.”

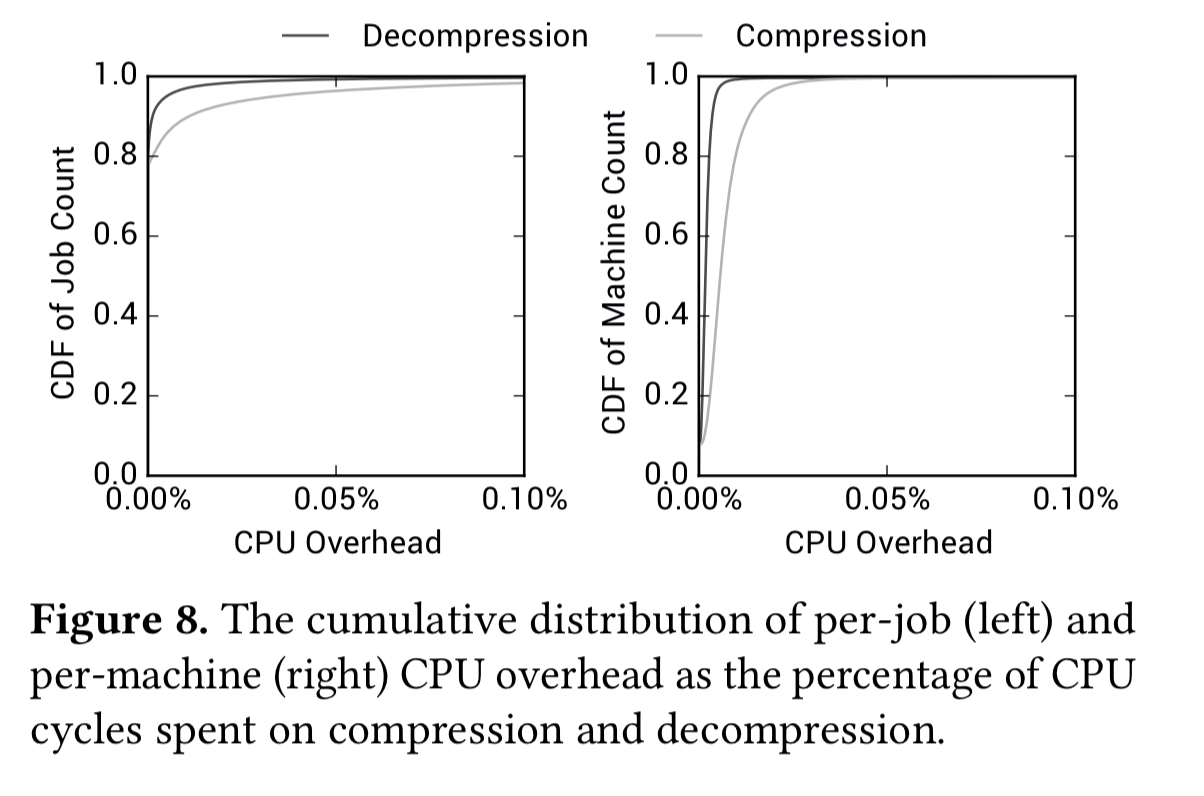

There are very low promotion rates in practice, both before and after deployment of the autotuner. CPU overhead for compression and decompression is very low as well (0.001% and 0.005% respectively).

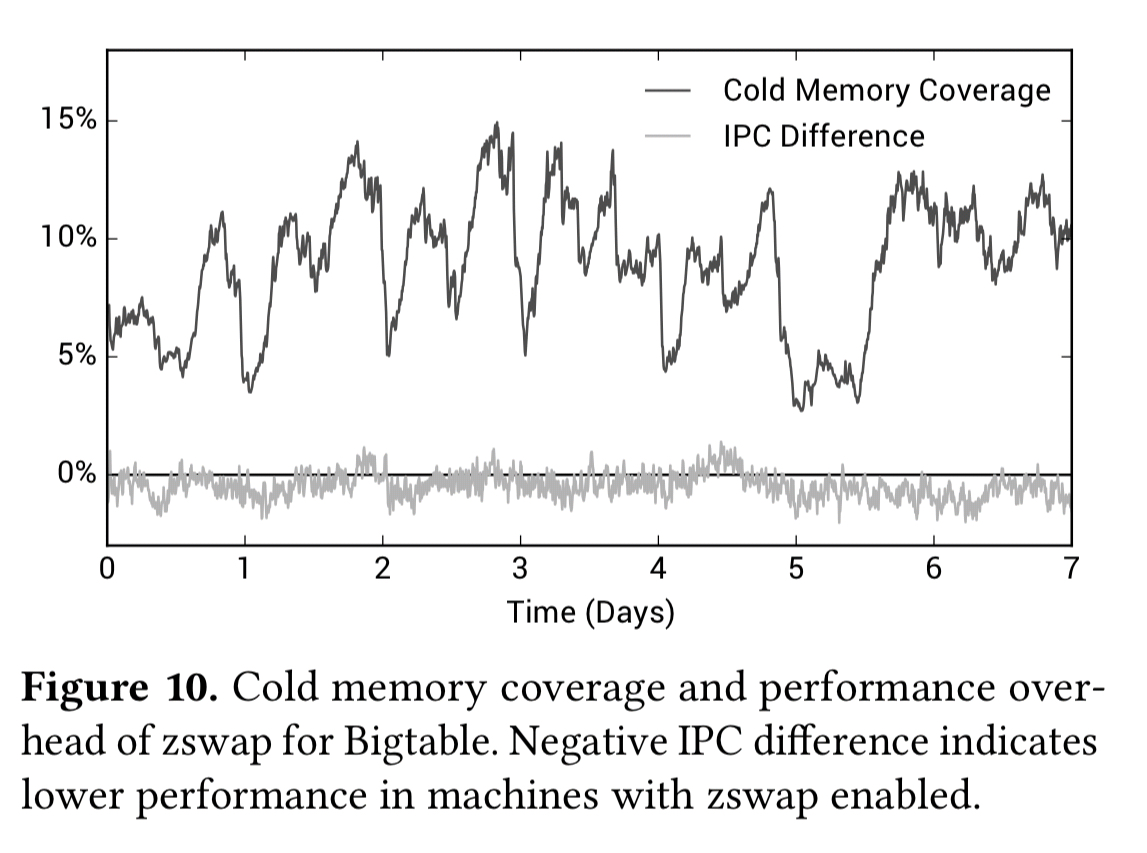

One of the biggest consumers of DRAM is Bigtable, storing petabytes of data in memory and serving millions of operations per second. The following chart shows an A/B test result for Bigtable with and without zswap enabled. During this period site engineers monitored application-level performance metrics and observed no SLO violations.

For Bigtable, zswap achieves 5-15% cold memory coverage.

Our system has been in deployment in Google’s WSC for several years and our results show that this far memory tier is very effective in saving memory CapEx costs without negatively impacting application performance… Ultimately an exciting end state would be one where the system uses both hardware and software approaches and multiple tiers of far memory (sub-µs tier-1 and single µs tier-2), all managed intelligently with machine learning and working harmoniously to address the DRAM scaling challenge.