RobinHood: tail latency aware caching – dynamic reallocation from cache-rich to cache-poor Berger et al., OSDI’18

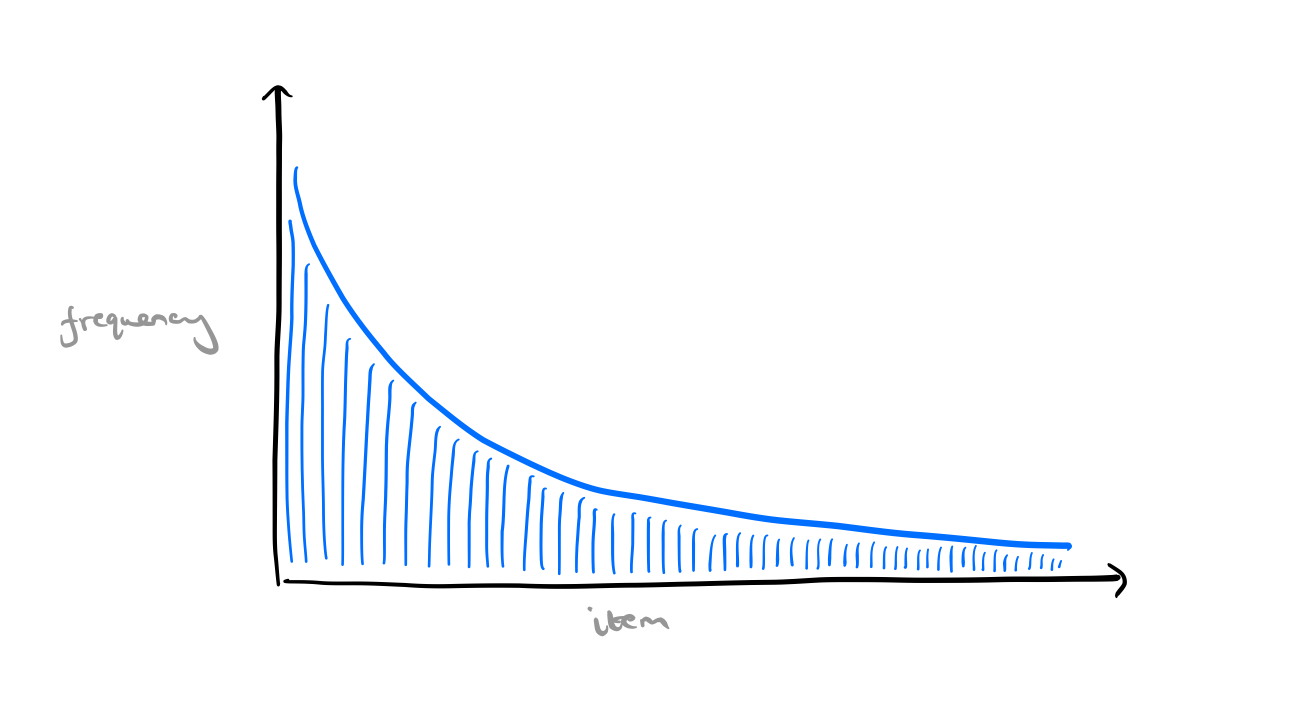

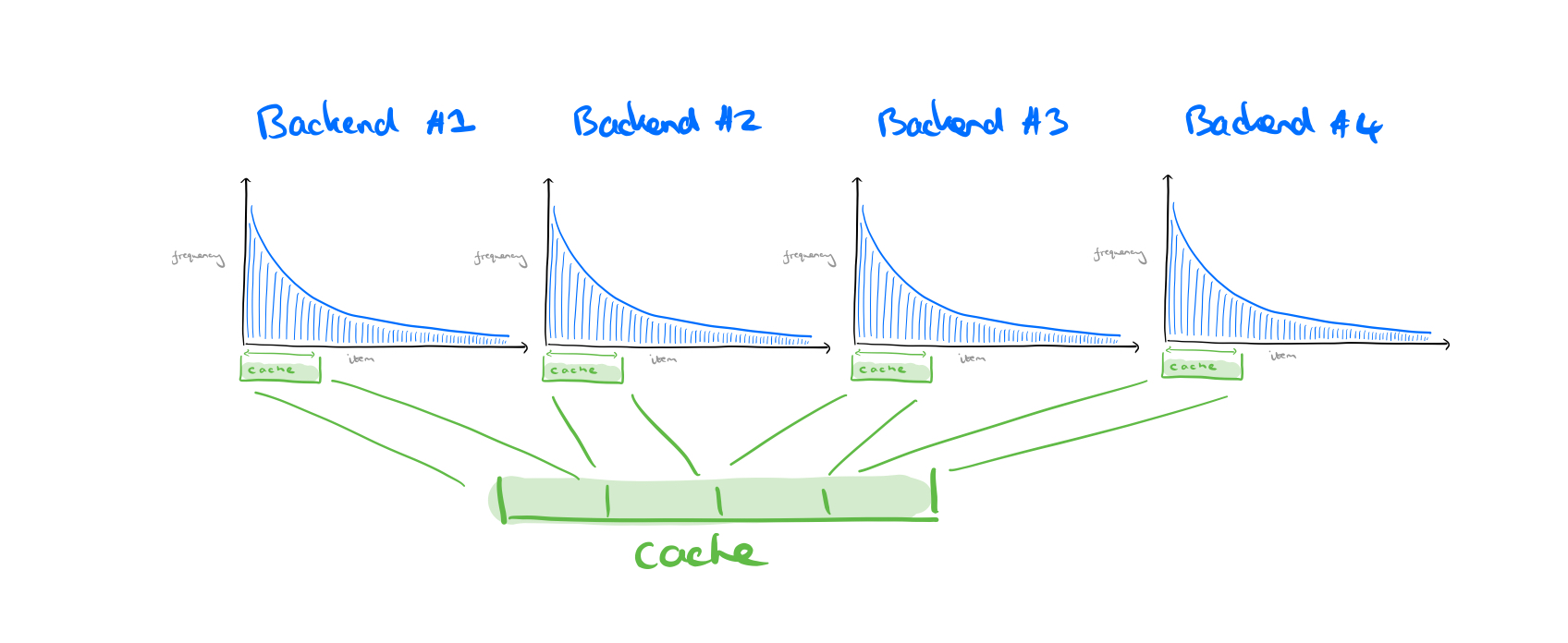

It’s time to rethink everything you thought you knew about caching! My mental model goes something like this: we have a set of items that probably follow a power-law of popularity.

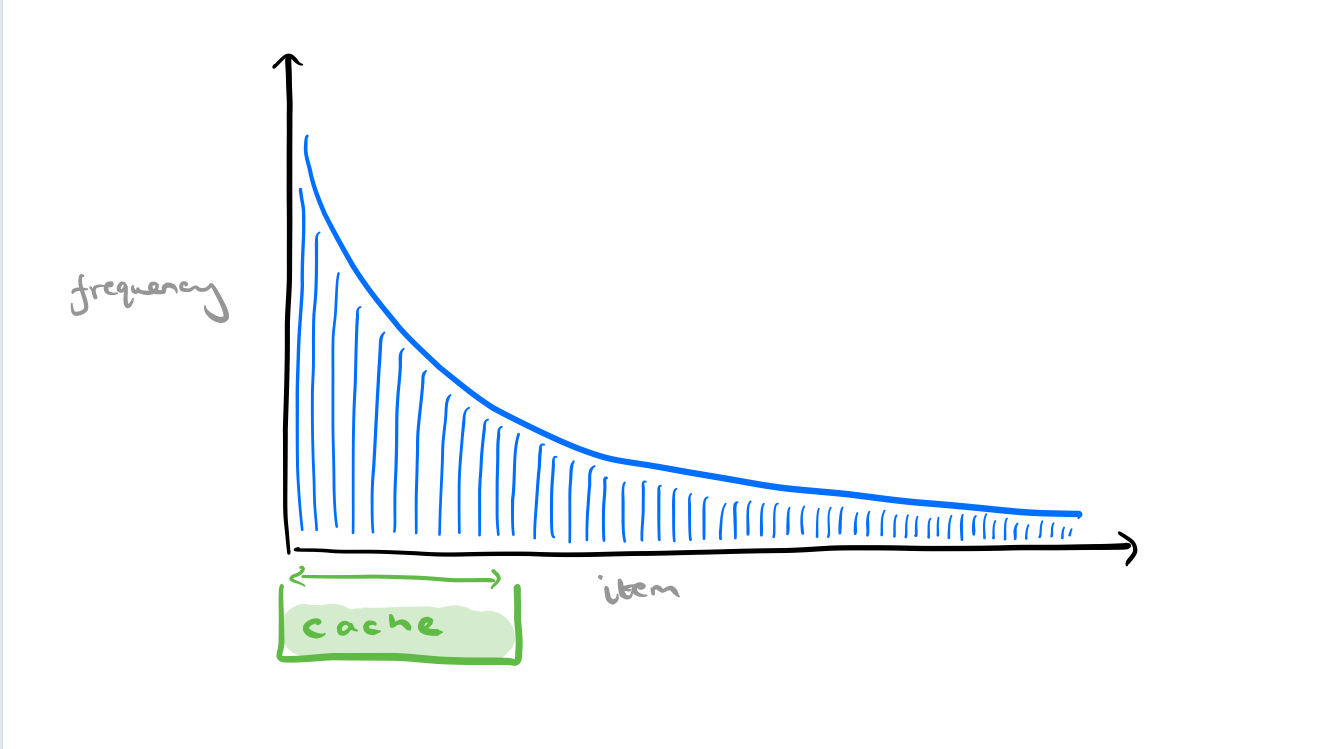

We have a certain finite cache capacity, and we use it to cache the most frequently requested items, speeding up request processing.

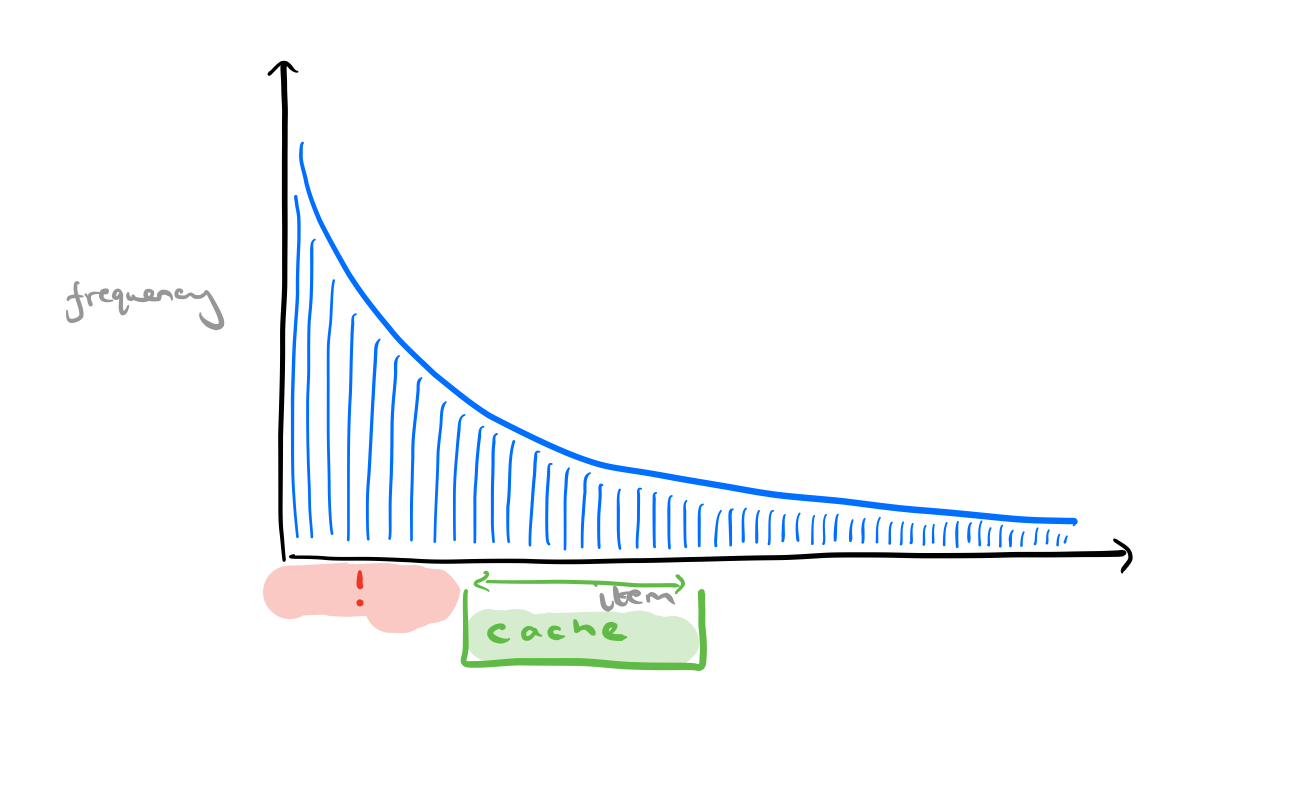

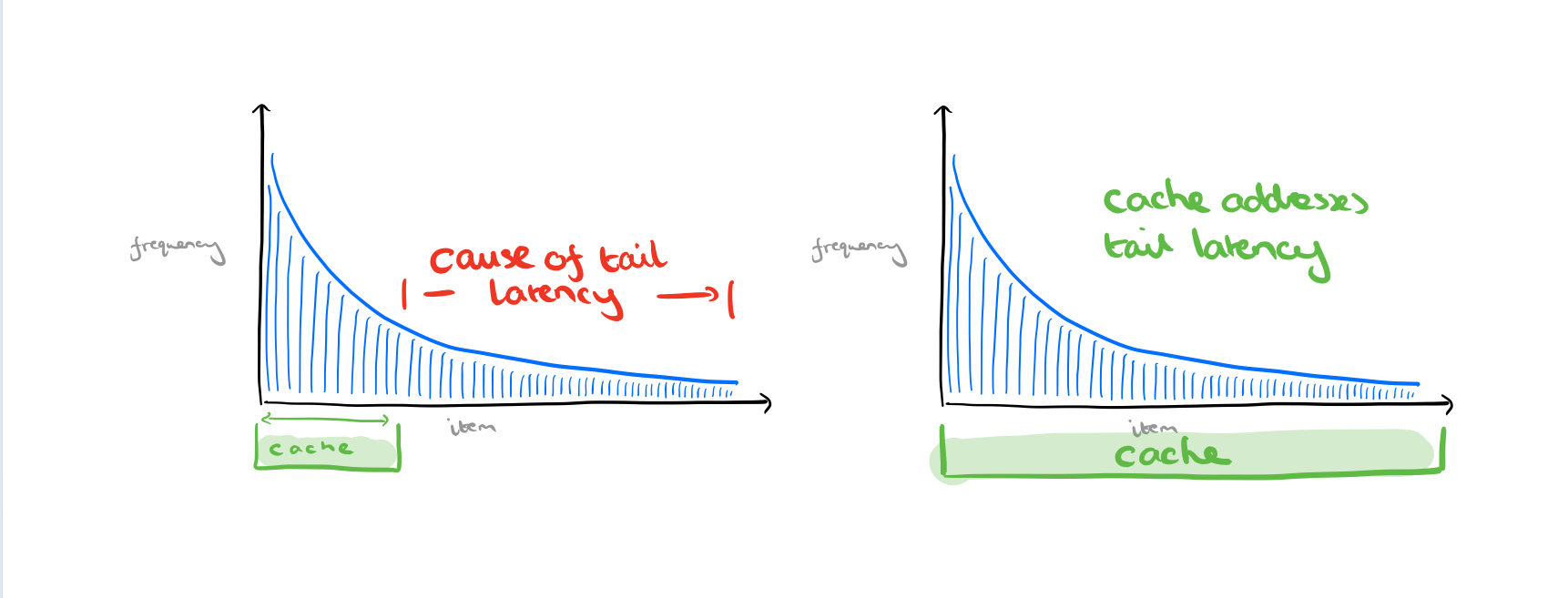

Now, there’s a long tail of less frequently requested items, and if we request one of these that’s not in the cache the request is going to take longer (higher latency). But it makes no sense whatsoever to try and improve the latency for these requests by ‘shifting our cache to the right.’

Hence the received wisdom that unless the full working set fits entirely in the cache, then a caching layer doesn’t address tail latency.

So far we’ve been talking about one uniform cache. But in a typical web application one incoming request might fan out to many back-end service requests processed in parallel. The OneRF page rendering framework at Microsoft (which serves msn.com, microsoft.com and xbox.com among others) relies on more than 20 backend systems for example.

The cache is shared across these back-end requests, either with a static allocation per back-end that has been empirically tuned, or perhaps with dynamic allocation so that more popular back-ends get a bigger share of the cache.

The thing about this common pattern is that we need to wait for all of these back-end requests to complete before returning to the user. So improving the average latency of these requests doesn’t help us one little bit.

Since each request must wait for all of its queries to complete, the overall request latency is defined to be the latency of the request’s slowest query. Even if almost all backends have low tail latencies, the tail latency of the maximum of several queries could be high.

(See ‘The Tail at Scale’).

The user can easily see P99 latency or greater.

Techniques to mitigate tail latencies include making redundant requests, clever use of scheduling, auto-scaling and capacity provisioning, and approximate computing. Robin Hood takes a different (complementary) approach: use the cache to improve tail latency!

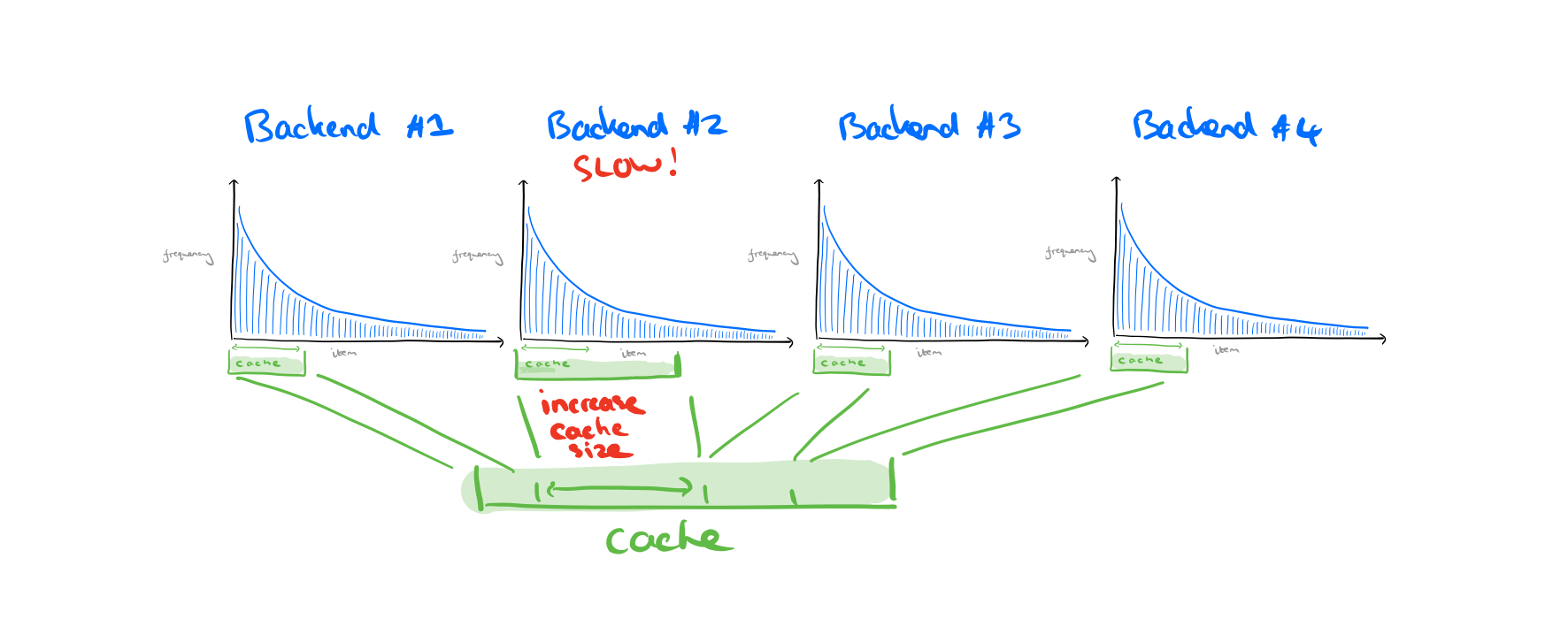

Robin Hood doesn’t necessarily allocate caching resources to the most popular back-ends, instead, it allocates caching resources to the backends (currently) responsible for the highest tail latency.

…RobinHood dynamically allocates cache space to those backends responsible for high request tail latency (cache-poor) backends, while stealing space from backends that do not affect the request tail latency (cache-rich backends). In doing so, Robin Hood makes compromises that may seem counter-intuitive (e.g., significantly increasing the tail latencies of certain backends).

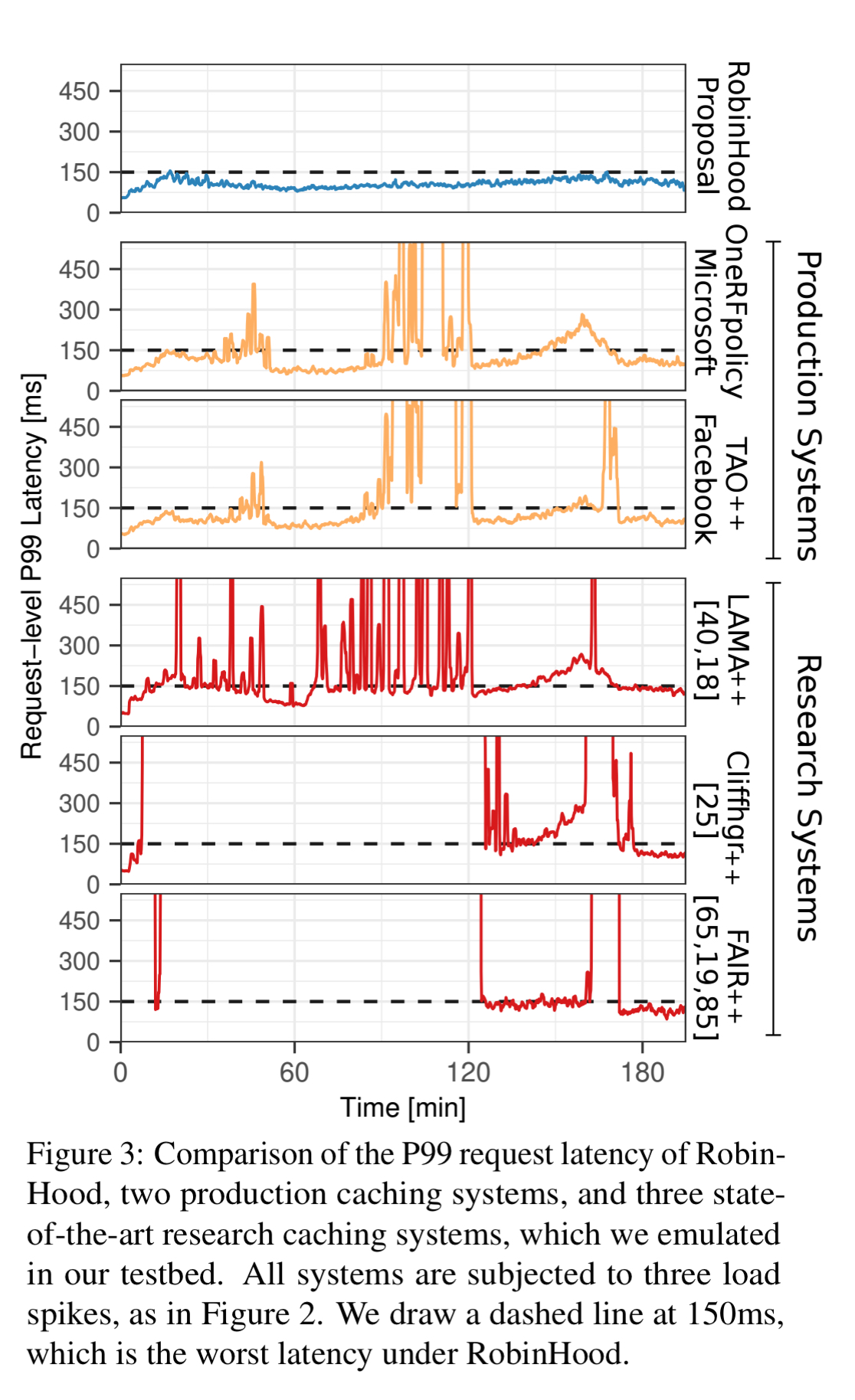

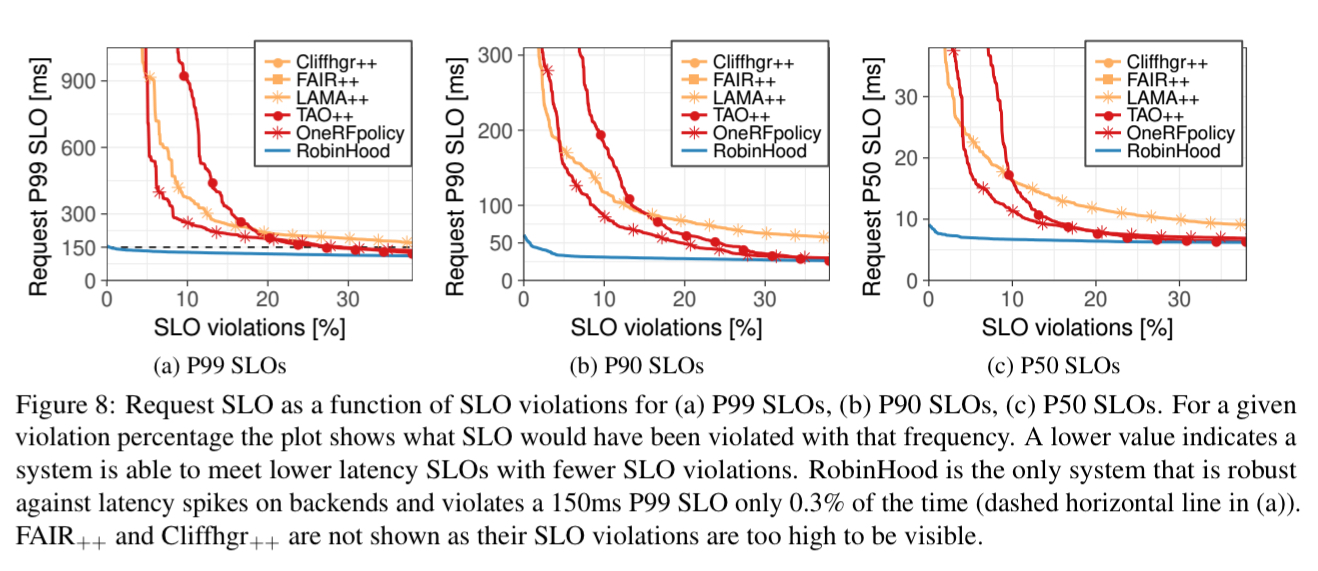

If you’re still not yet a believer that caching can help with tail latencies, the evaluation results should do the trick. RobinHood is evaluated with production traces from a 50-server cluster with 20 different backend systems. It’s able to address tail latency even when working sets are much larger than the cache size.

In the presence of load spikes, RobinHood meets a 150ms P99 goal 99.7% of the time, whereas the next best policy meets this goal only 70% of the time.

Look at that beautiful blue line!

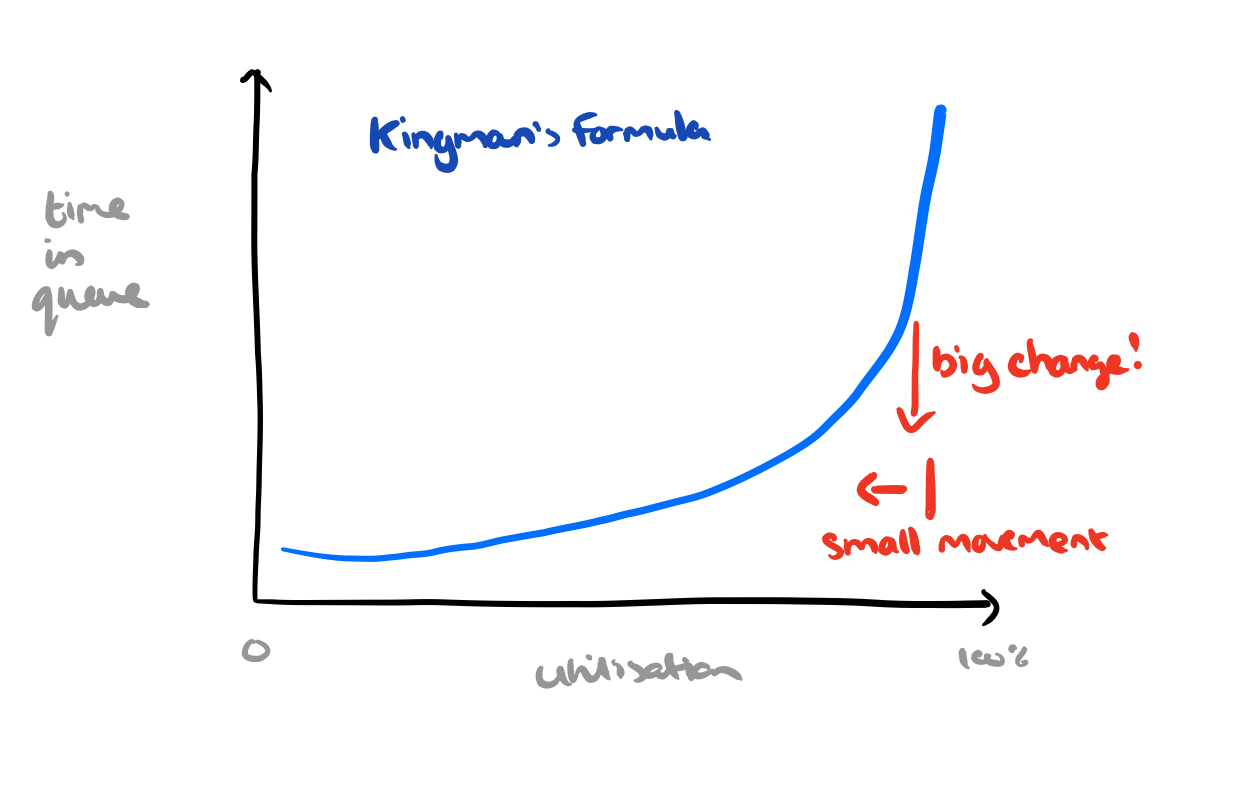

When RobinHood allocates extra cache space to a backend experience high tail latency, the hit ratio for that backend typically improves. We get a double benefit:

- Since backend query latency is highly variable in practice, decreasing the number of queries to a backend will decrease the number of high-latency queries observed, improving the P99 request latency.

- The backend system will see fewer requests. As we’ve studied before on The Morning Paper, small reductions in resource congestion can have an outsized impact on backend latency once a system has started degrading.

Caching challenges

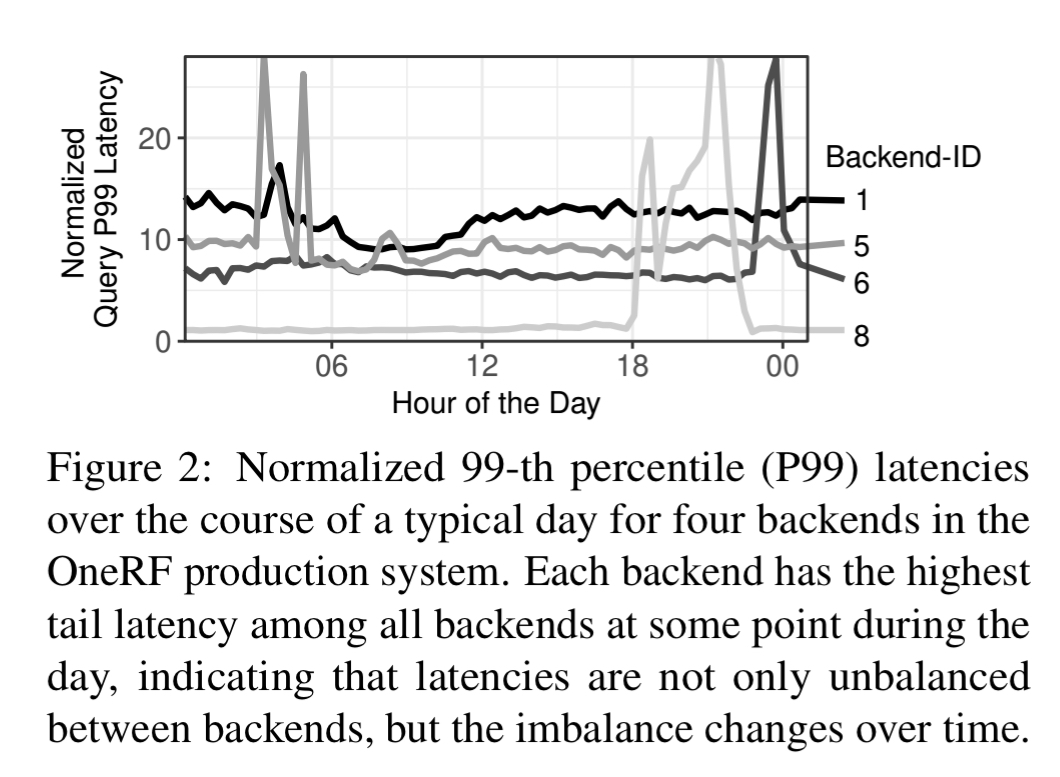

Why can’t we just figure out which backends contribute the most to tail latency and just statically assign more cache space to them? Because the latencies of different backends tends to vary wildly over time: they are complex distributed systems in their own right. The backends are often shared across several customers too (either within the company, or perhaps you’re calling an external service). So the changing demands from other consumers can impact the latency you see.

Most existing cache systems implicitly assume that latency is balanced. They focus on optimizing cache-centric metrics (e.g., hit ratio), which can be a poor representation of overall performance if latency is imbalanced.

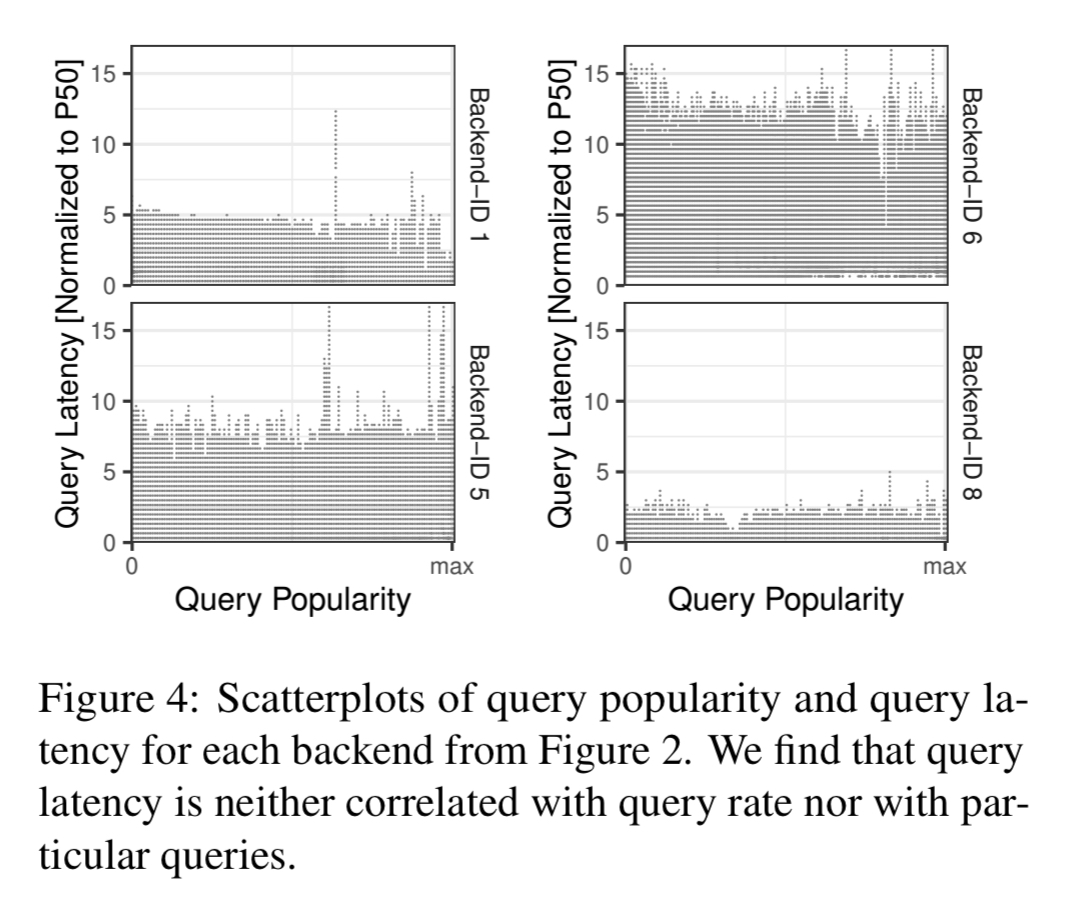

Query latency is not correlated with query popularity, but instead reflects a more holistic state of the backed system at some point in time.

An analysis of OneRF traces over a 24 hour period shows that the seventh most queried backend receives only about 0.06x as many queries as the most queried backend, but has 3x the query latency. Yet shared caching systems inherently favour backends with higher query rates (they have more shots at getting something in the cache).

The RobinHood caching system

RobinHood operates in 5 second time windows, repeatedly taxing every backend by reclaiming 1% of its cache space and redistributing the wealth to cache-poor backends. Within each window RobinHood tracks the latency of each request, and chooses a small interval (P98.5 to P99.5) around P99 to focus on, since the goal is to minimise the P99 latency. For each request that falls within this interval, RobinHood tracks the ID of the backend corresponding to the slowest query in the request. At the end of the window RobinHood calculates the request blocking count (RBC) of each backend – the number of times it was responsible for the slowest query.

Backends with a high RBC are frequently the bottleneck in slow requests. RobinHood thus considers a backend’s RBC as a measure of how cache-poor it is, and distributes the pooled tax to each backend in proportion to its RBC.

RBC neatly encapsulates the dual considerations of how likely a backend is to have high latency, and how many times that backend is queried during request processing.

Since some backends are slow to make use of the additional cache space (e.g., if their hit rations are already high). RobinHood monitors the gap between the allocated and used cache capacity for each backend, and temporarily ignores the RBC of any backend with more than a 30% gap.

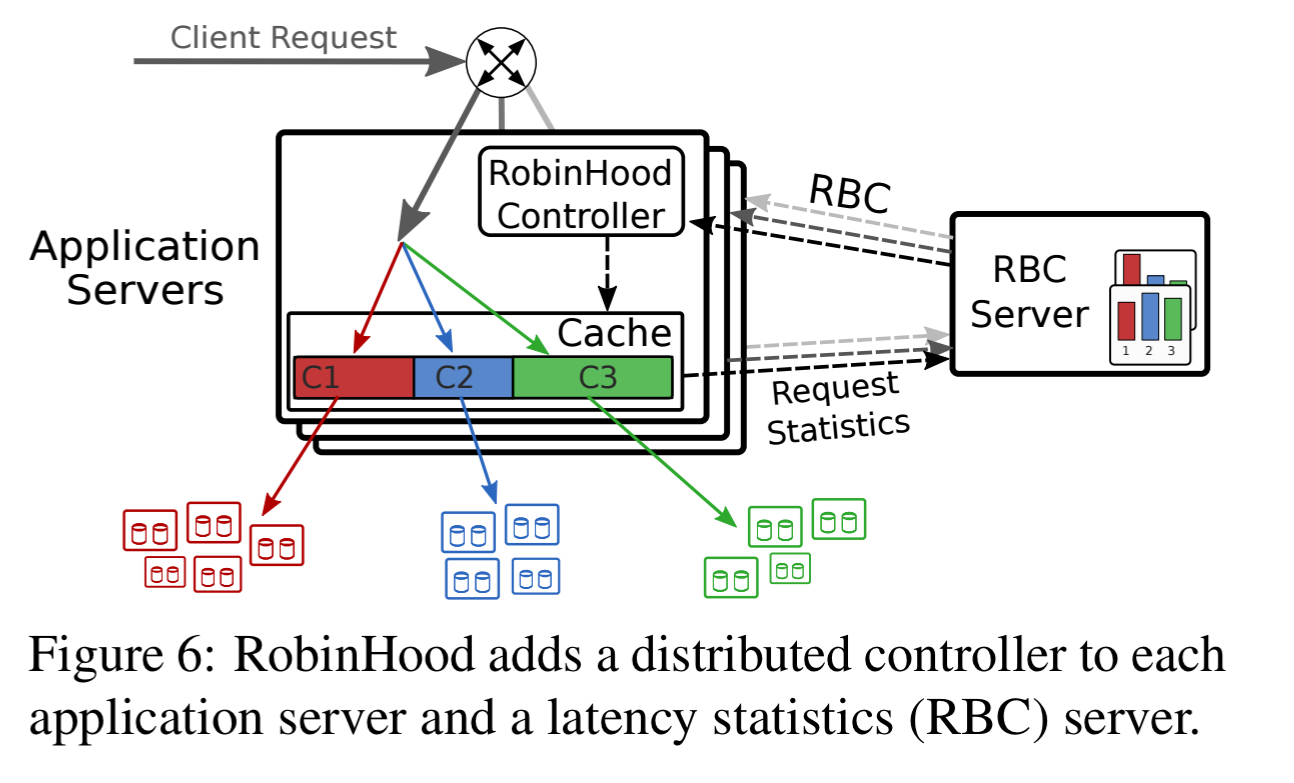

When load balancing across a set of servers RobinHood makes allocation decisions locally on each server. To avoid divergence of cache allocations over time, RobinHood controllers exchange RBC data. With a time window of 5 seconds, RobinHood caches converge to the average allocation within about 30 minutes.

The RobinHood implementation uses off-the-shelf memcached instances to form the caching layer in each application server. A lightweight cache controller at each node implements the RobinHood algorithm and issues resize commands to the local cache partitions. A centralised RBC server is used for exchange of RBC information. RBC components store only soft state (aggregated RBC for the last one million requests, in a ring buffer), so can quickly recover after a crash or restart.

Key evaluation results

The RobinHood evaluation is based on detailed statistics of production traffic in the OneRF system for several days in 2018. The dataset describes queries to more than 40 distinct backend systems. RobinHood is compared against the existing OneRF policy, the policy from Facebook’s TAO, and three research systems Cliffhanger, FAIR, and LAMA. Here are the key results:

- RobinHood brings SLO violations down to 0.3%, compared to 30% SLO violations under the next best policy.

- For quickly increasing backend load imbalances, RobinHood maintains SLO violations below 1.5%, compared to 38% SLO violations under the next best policy.

- Under simultaneous latency spikes, RobinHood maintains less than 5% SLO violations, while other policies do significantly worse.

- Compared to the maximum allocation for each backend under RobinHood, even a perfectly clairvoyant static allocation would need 73% more cache space.

- RobinHood introduces negligible overhead on network, CPU, and memory usage.

Our evaluation shows that RobinHood can reduce SLO violations from 30% to 0.3% for highly variable workloads such an OneRF. RobinHood is also lightweight, scalable, and can be deployed on top of an off-the-shelf software stack… RobinHood shows that, contrary to popular belief, a properly designed caching layer can be used to reduce higher percentiles of request latency.

Could this be used to improve VR latency?

This paper review comes just at the time I was drafting an internal blog post about caching — superb stuff and eerily apposite.

As usual your hit rate is phenomenally high.