Apps, trackers, privacy, and regulators: a global study of the mobile tracking ecosystem Razaghpanah et al., NDSS’18

Sadly you probably won’t be surprised to learn that this study reveals user tracking is widespread within the mobile app (Android) ecosystem. The focus is on third-party services included in apps, identified by the network domains they try to connect to. These services typically operate in the background, inheriting the permissions of the apps in which they are embedded, and offer no visual clue within the app as to what is happening.

In this work, we focus on studying third-party services whose main function relies on collecting tracking information from users, which we henceforth refer to as Advertising and Tracking Services (ATS).

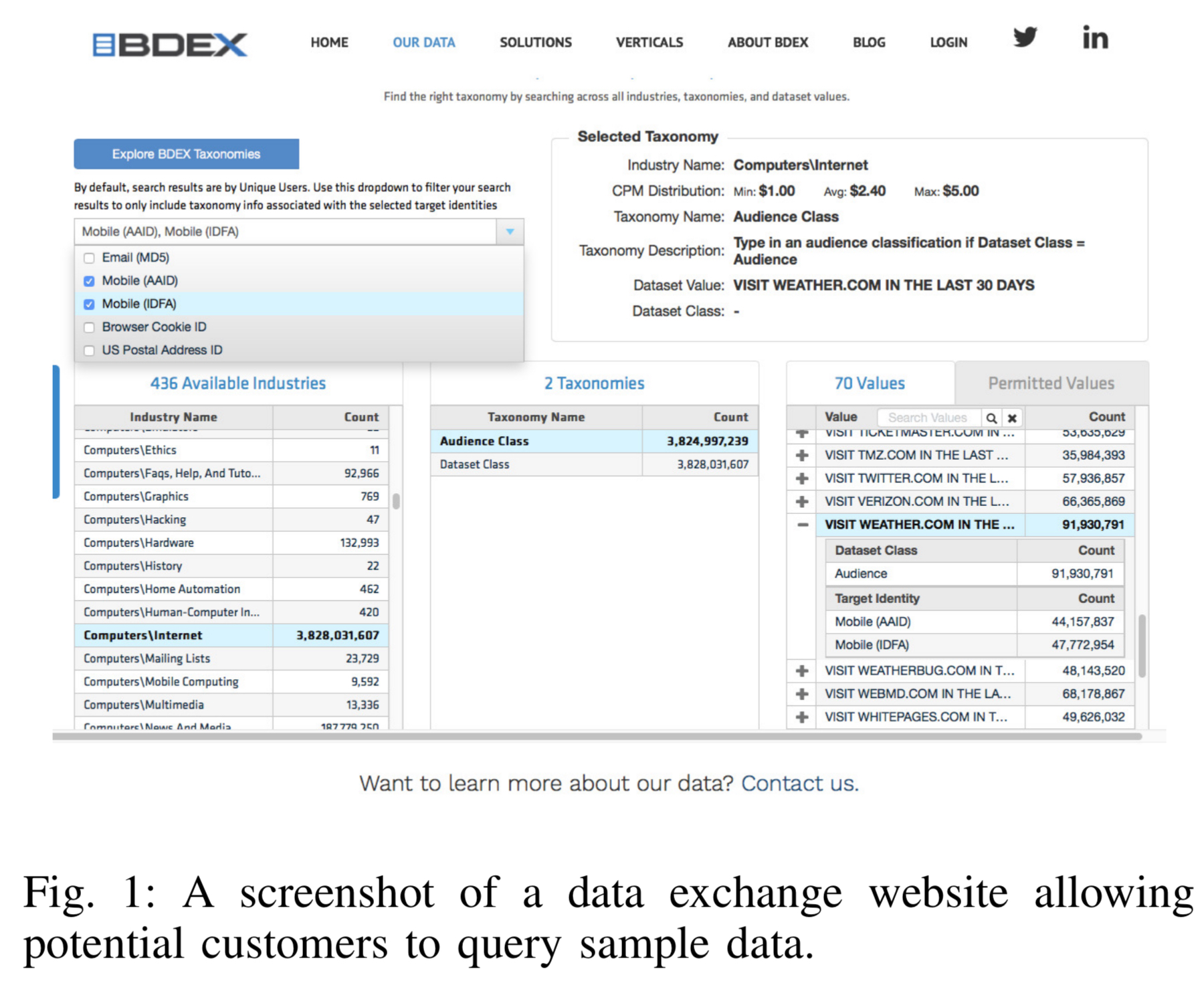

The data collected by such services mostly ends up in the hands of data brokers and exchanges where it is sold. Want to buy data for people who have visited weather.com on a mobile device in the last 30 days? Go ahead…

While there are regulations, such as the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) in the United States, and the forthcoming GDPR in the EU, to date these seem to have had little effect in curbing practices. For example, “there are still countless examples of games and children’s apps that use third party services collecting tracking data without parental consent.”

Overall, the authors conclude that…

… a small number of companies have a monopoly on controlling a large portion of the ecosystem and they have the ability to track users and share the tracking data with other entities, all with little to no transparency.

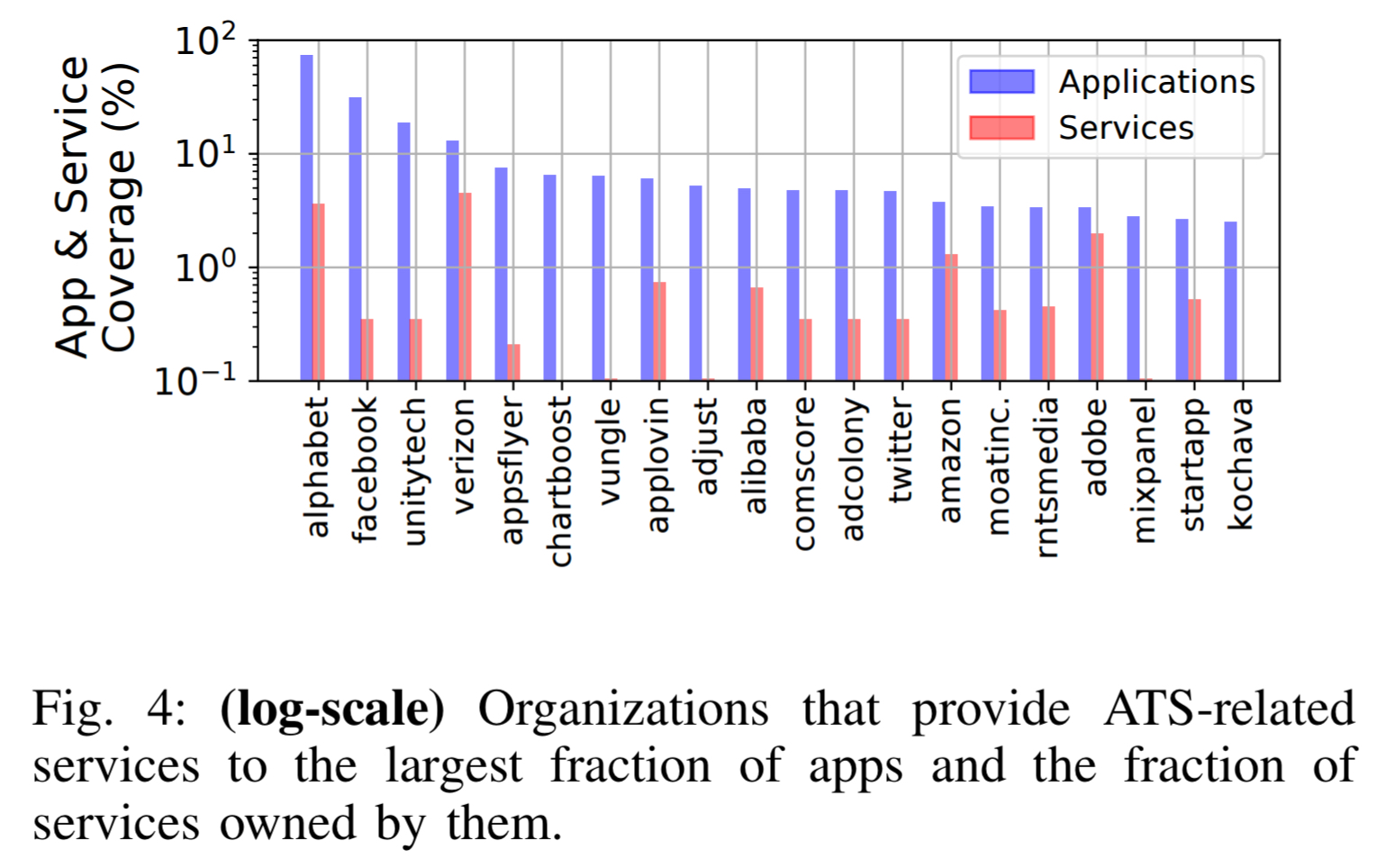

Since this is a study of the Android app ecosystem, you might think that e.g., Google could enforce stricter rules in the Play store to clamp down on this behaviour. However, with no further comment I leave you with Figure 4 from the paper, showing the companies that are the major perpetrators and beneficiaries of ATS-related services.

We find that Alphabet has penetration in over 73% of all our measured apps with ownership of only 3.6% of all ATS and ATS-C service. Facebook — known by average users for providing social networking services — has ATS presence in over 31% of all measured apps while owning only 0.35% of all ATS and ATS-C services through the Facebook Graph API.

(ATS-C in the above stands for Advertising and Tracking Services Capable. These are domains that collect tracking information, but have a primary purpose other than specifically providing ads and analytics).

To collect the data for the study, the authors rely on a user base voluntarily installing the Lumen Privacy Monitor app (previously called Haystack, and available at https://www.haystack.mobi). Data was collected from about 11,000 users. If ever you see a vendor, especially a vendor whose business is tracking people for the purposes of serving advertisements, offering a VPN “for your own protection,” you would do well to be wary:

Lumen works by leveraging the Android VPN permission to capture and analyze network traffic, including encrypted flows, locally on the device and in user-space. Lumen inserts itself as a middleware between apps and the network interface… It runs locally on the device and intercepts all network traffic — both over WiFi and the mobile network — without requiring root permissions… The use of the VPN permission to analyze app traffic on user-space is not novel.

The overall data collected by Lumen (as of August 2017) contains the ports, origin application, destination domain, requested app permissions, IP address, TLS-handshake information, and the types of unique identifiers leaked by over 8.5M flows from 14,599 apps to 40,553 unique fully-qualified domain names and 13,453 unique second level domains. (All gathered with explicit consent).

Any third party library, even ATS-C libraries whose primary purpose is not providing advertising and tracking services, can piggyback app permissions to access UIDs — or any other permission protected data — or obtain them via side-channels (without user consent) to track the use activities across different apps on the same device.

The team use a combination of classification, manual inspection, and known ATS domains to classify the third-party domains that libraries were connecting to.

Key findings

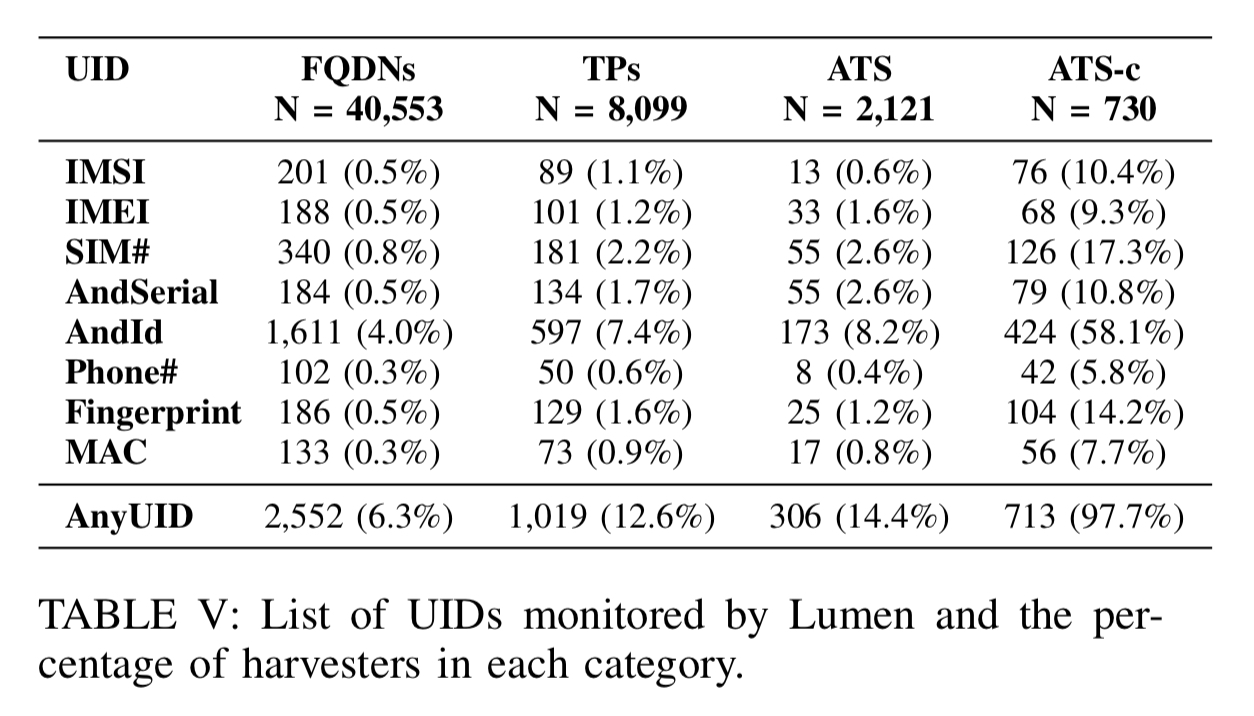

The authors identified 2,552 different domains harvesting one or more of the UIDs from the following table, including 223 domains previously unknown to be ATS domains:

We find that third-party domains, representing only 20.0% of all domains, are responsible for a disproportionate fraction (39.9%) of all UID harvesting… The most common value harvested by ATSes is the semi-persistent Android ID. Interestingly the Android ID is also collected by ATS-C domains along with at least one persistent UID in 34% of cases. In addition to making it possible for ATS-C services to persistently track a user, this behaviour contradicts Android’s developer policy center guidelines which state that the Android ID should not be associated with any other personally-identifiable information.

The IMEI, a persistent value uniquely identifying a mobile device, is the fourth most commonly harvested UID, and disproportionately gathered by ATS and ATS-C domains.

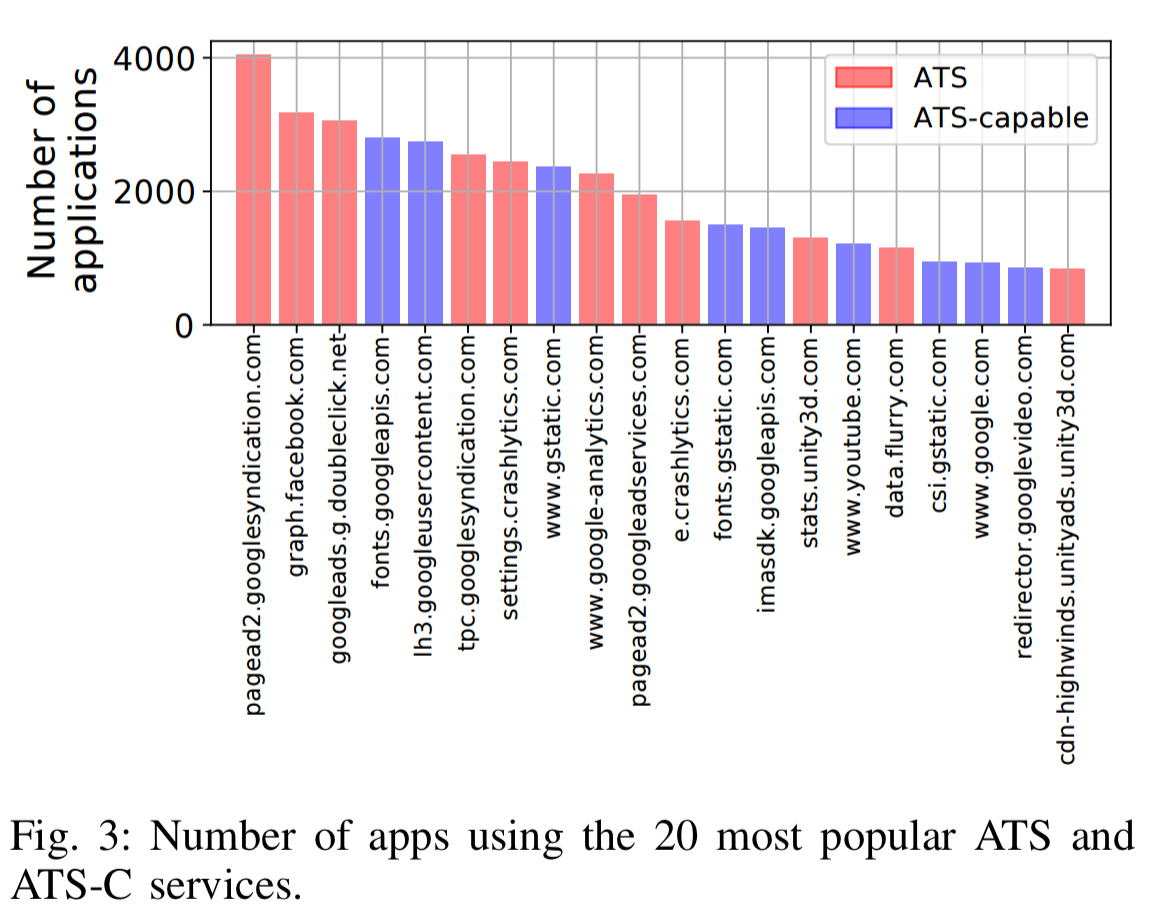

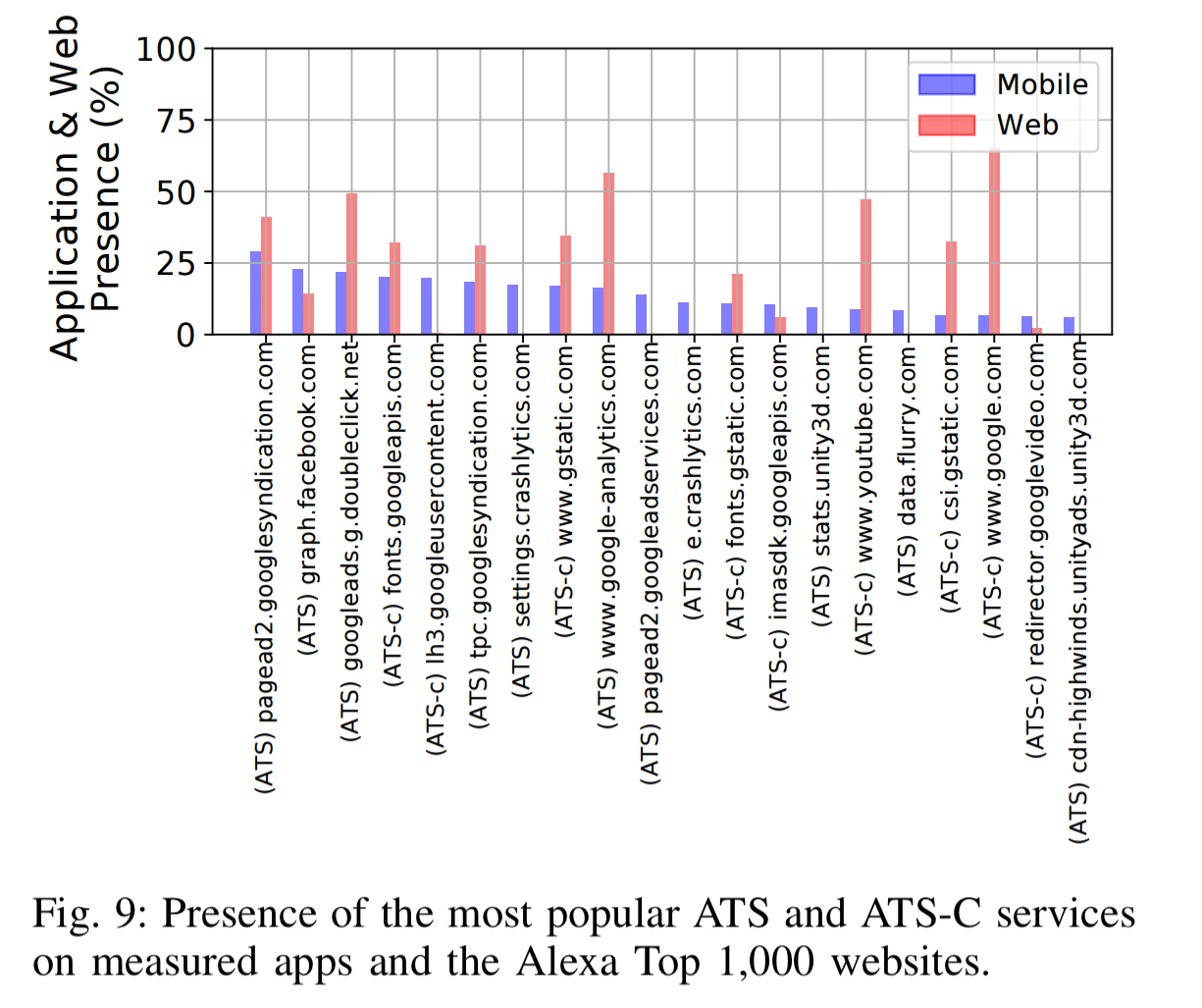

16 of the 20 most pervasive ATS and ATS-C domains are owned by Alphabet:

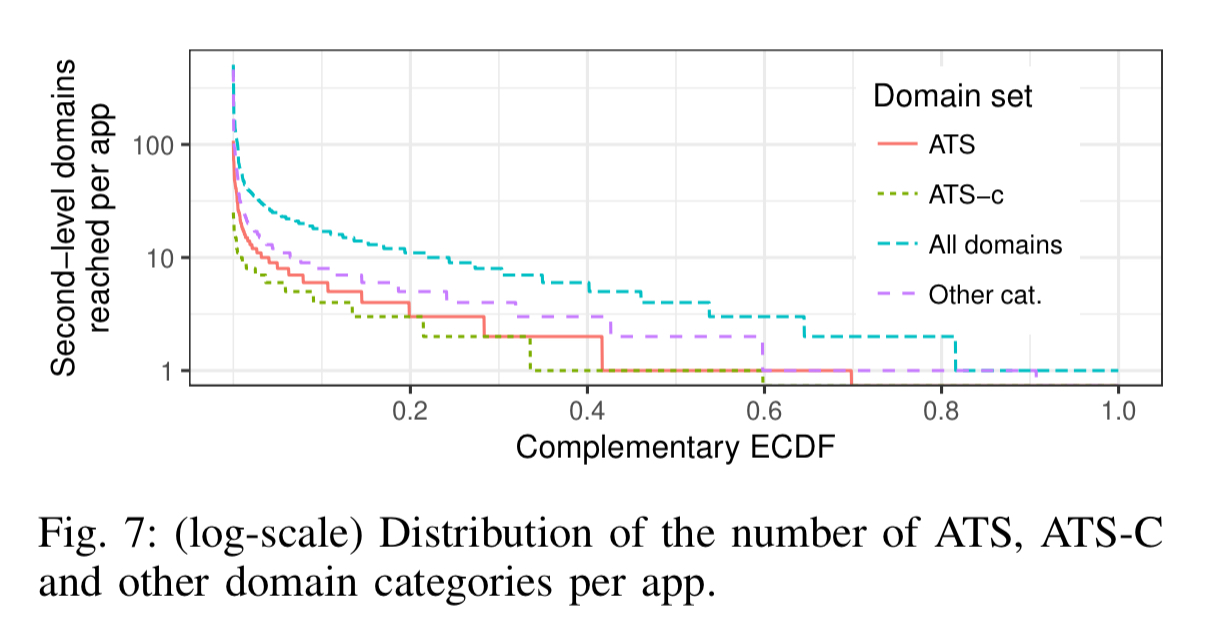

Applications are not happy to leak information just to one third party though. 82% of apps connect to at least one ATS domain (75% to at least one ATS-C domain), and 29% connect to at least five ATS domains (29% connect to at least five ATS-C domains also). Games and educational apps turn out to be the worst offenders.

What starts on mobile doesn’t stay on mobile. 39% of all identified ATSes are also present as third-parties in Alexa Top 1000 websites.

The ability to perform cross-device tracking would allow them to link mobile app and Web usage behavior and possibly reveal a very privacy-invasive insight into an individual’s virtual and real-world habits.

Regulatory impact

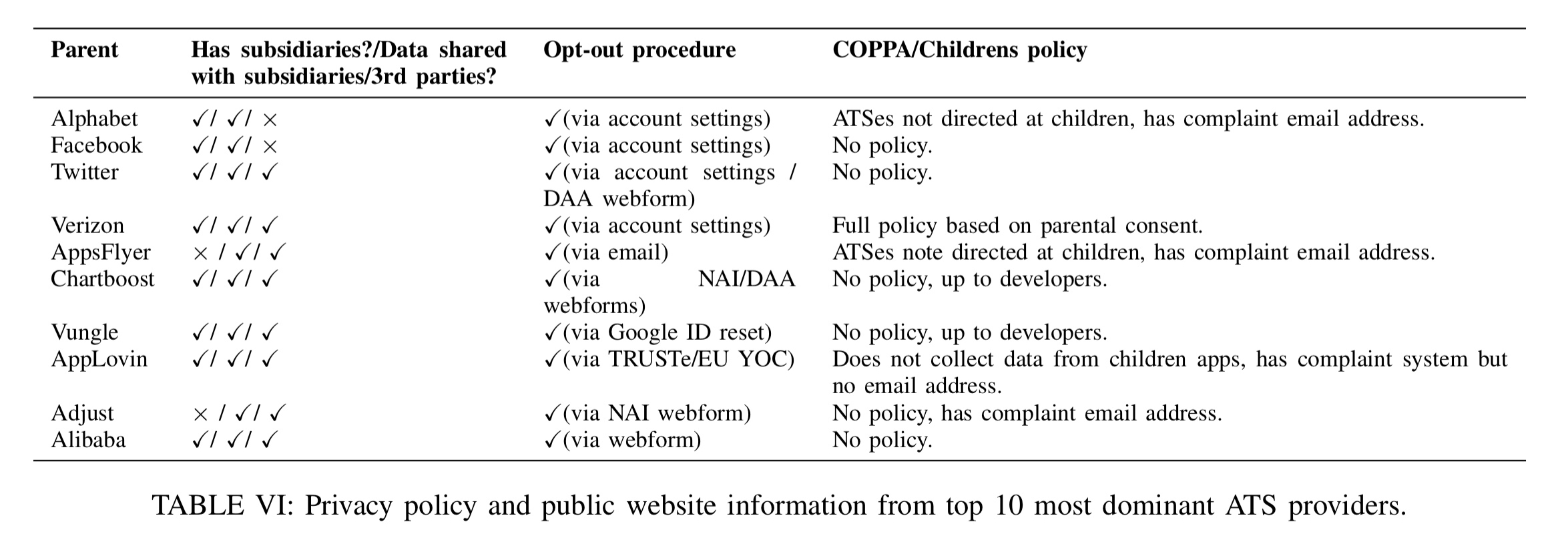

An analysis of the publicly available privacy policy information for the 10 most dominant ATS providers shows that with the exception of Alphabet and Facebook, all of them happily admit to sharing your data with third-parties. “Therefore, developers who use services provided by these organizations provide a gateway for more third-party organizations to track their users.”

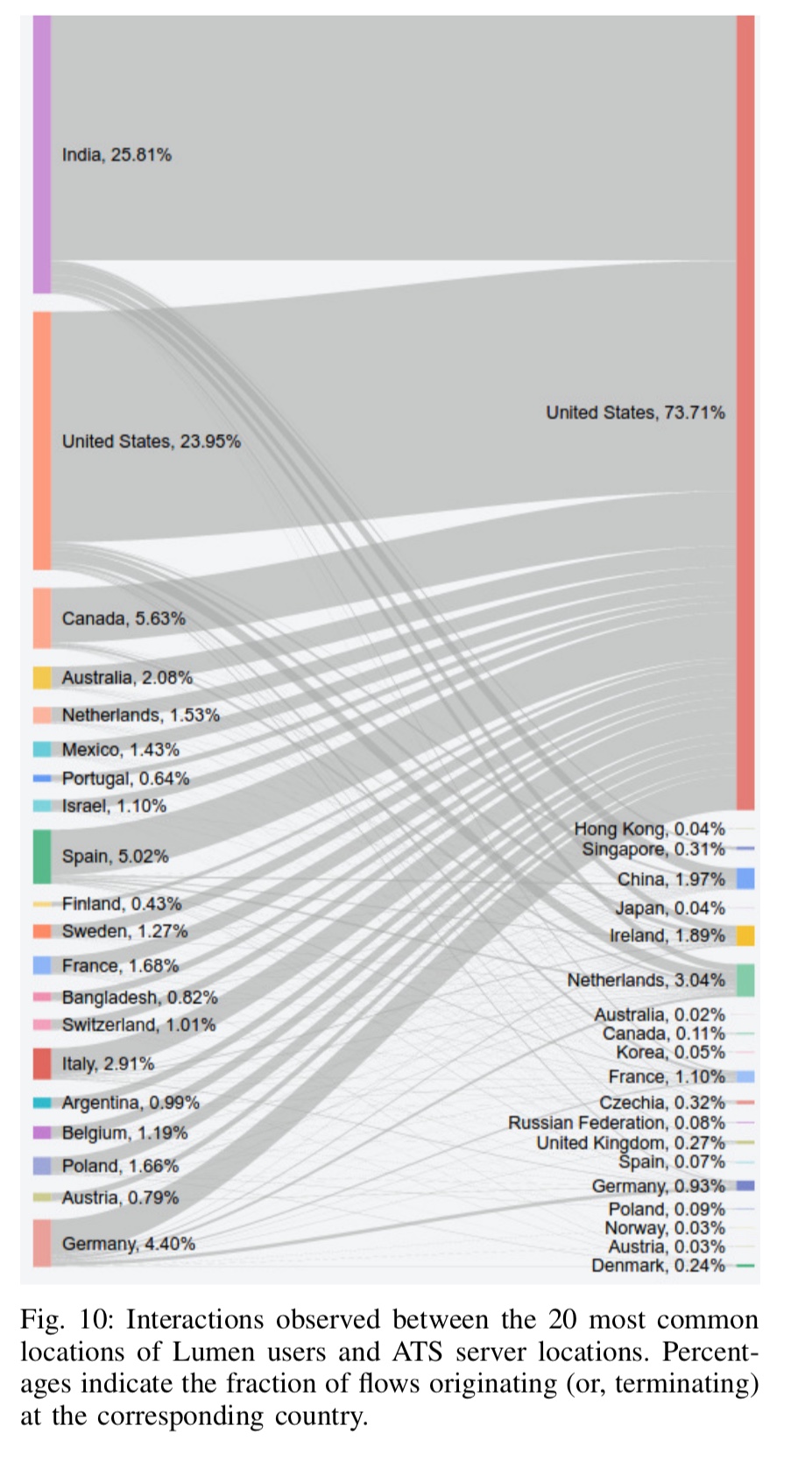

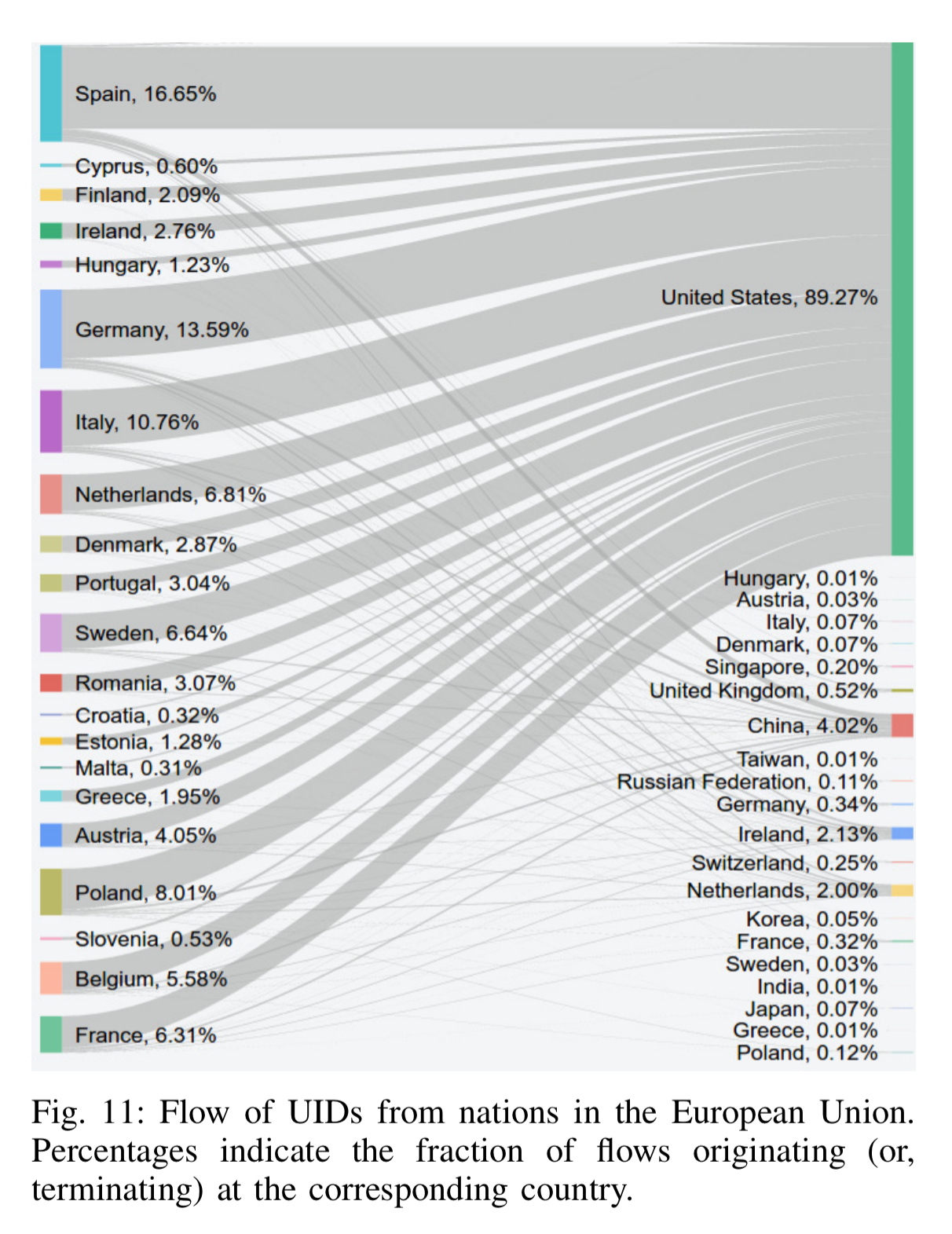

When we look at where the users are, and where the ATS services are, we can monitor the flow of tracking information across borders and jurisdictions. The United States hosts over 40% of all ATS servers, and those servers are at the terminating end of 73% of all ATS-related flows. Over 50% of all cross-border ATS traffic ends up in the United States.

We also find that even users from countries with strong consumer and privacy protection laws (e.g., Switzerland, Germany, and Spain) have sizable fractions of ATS-related traffic flowing into nations with weaker regulatory frameworks. Such trans-national flow of data makes it unclear which privacy and consumer protection laws are applicable to ATS-related data.

With regards to the EU in particular (and the forthcoming GDPR legislation), we can clearly see services hosted in the United States busily harvesting PII out of Europe:

We hope that our findings will spark and inform more public discourse and result in stronger regulatory frameworks to protect user privacy.

2 thoughts on “Apps, trackers, privacy, and regulators: a global study of the mobile tracking ecosystem”

Comments are closed.