Seamless offloading of web app computations from mobile device to edge clouds via HTML5 web worker migration, Jeong et al., SoCC’19 [^1]

This paper caught my eye for its combination of an intriguing idea (opportunistic offload of computation from mobile devices to the edge) and the elegance of the way the web worker interface supports this use case. It’s live migration – but for web workers instead of the more usual VMs or containers.

Why would we want to live migrate web workers?

Emerging mobile applications, such as mobile cloud gaming or augmented reality, require strict latency constraints as well as high computer power… A survey on the latency of games has reported that less than ~50ms of network latency is preferred for time-critical games, which is hard to achieve with a traditional cloud system where computing servers are located in datacenters far from clients…

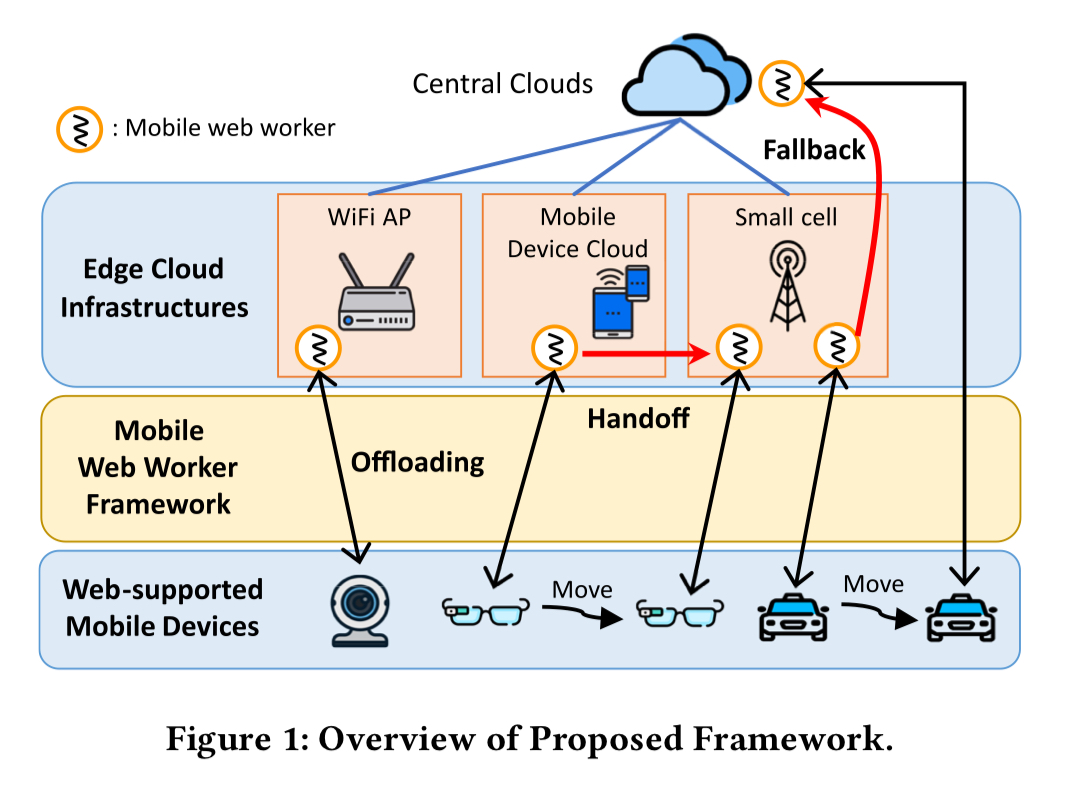

So you’ve got mobile devices without the computing power needed to deliver a great experience, and cloud computing that has all the needed power that’s too far away. Edge servers are the middle ground – more compute power than a mobile device, but with latency of just a few ms. The kind of edge server envisaged here might, for example, be integrated with your WiFi access point.

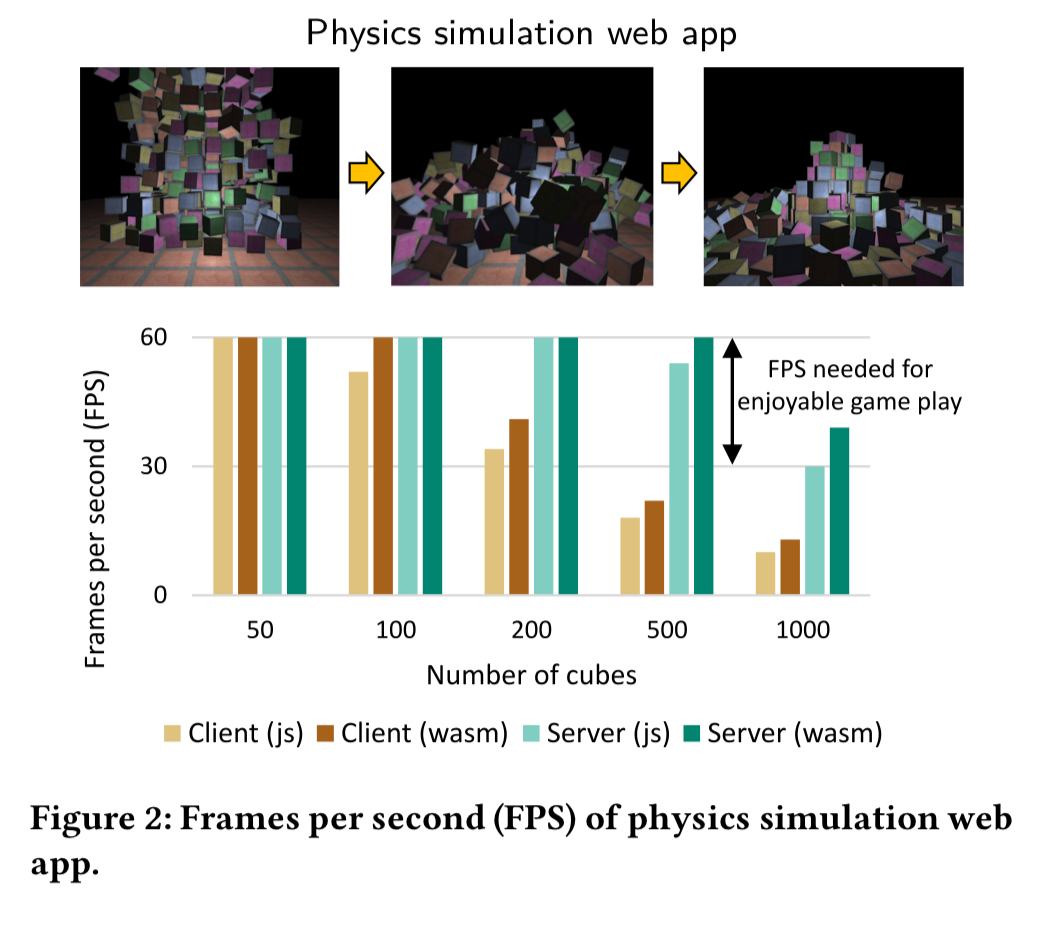

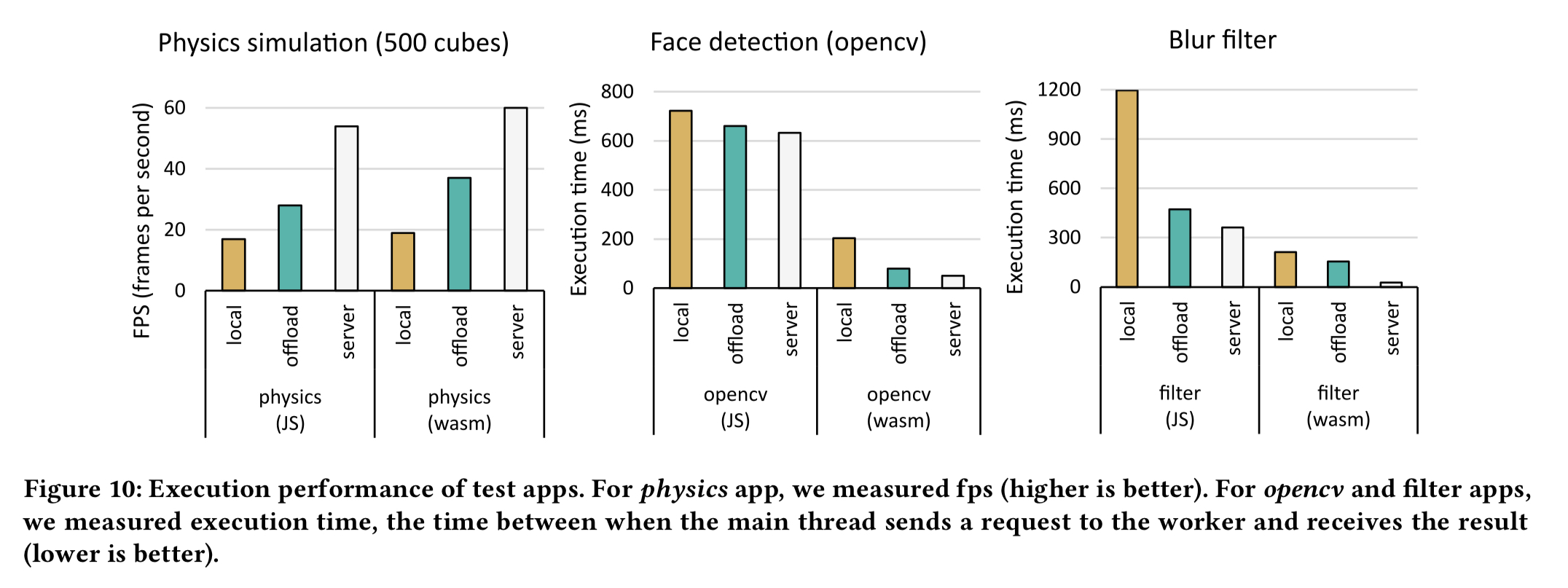

One example from the paper is an application using the ammo.js physics engine that simulates 3D cubes falling from the air. Ideally we’re looking for something in the range of 30-60 fps (frames per second). Client-side implementations in JavaScript and wasm can hold onto that frame rate until we get to a few hundred cubes. But at 500 cubes the client-side approach can no longer keep up, whereas a server-side implementation is good for 1000 cubes or more.

The design of the HTML5 Web Worker interface turns out to be a great match for migration – Workers are already designed to work on a separate thread communicating via message passing, and are typically used to offload expensive computation that you don’t want to do in the main thread with the user waiting.

Since interactivity is important for many mobile apps, computations are commonly run in web workers. As such, web workers are a natural target to offload to a more powerful server.

Challenges in web worker live migration

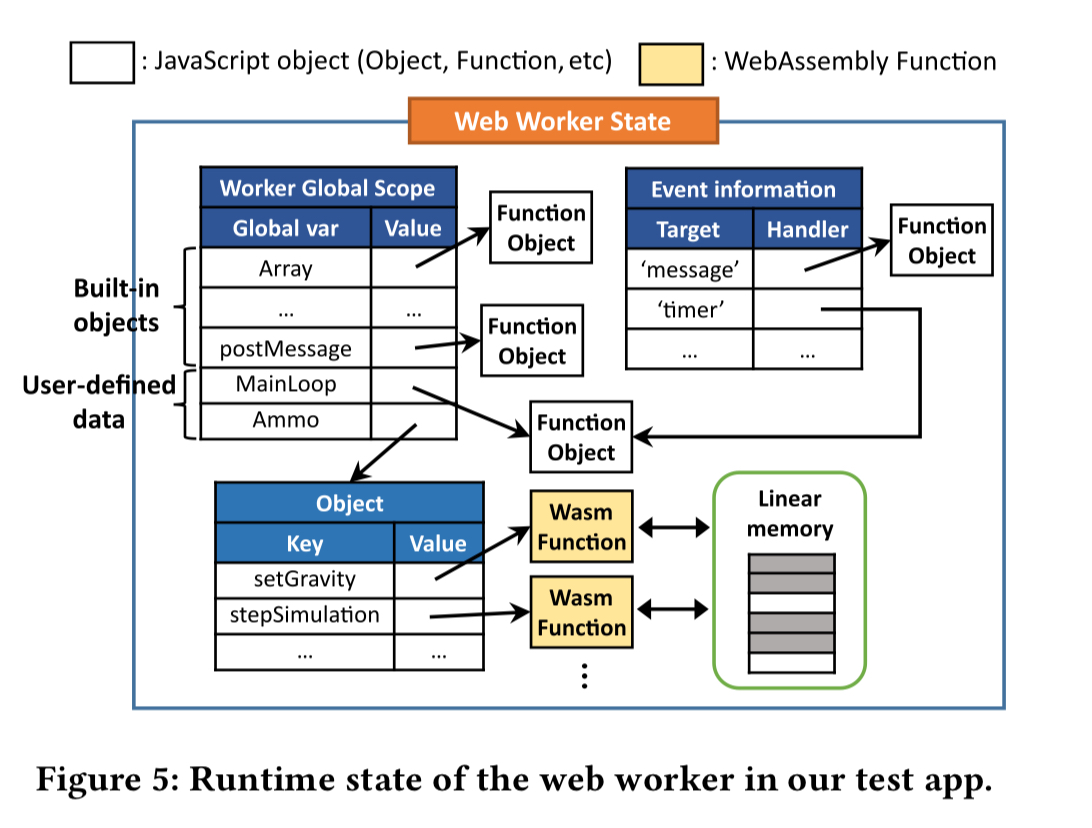

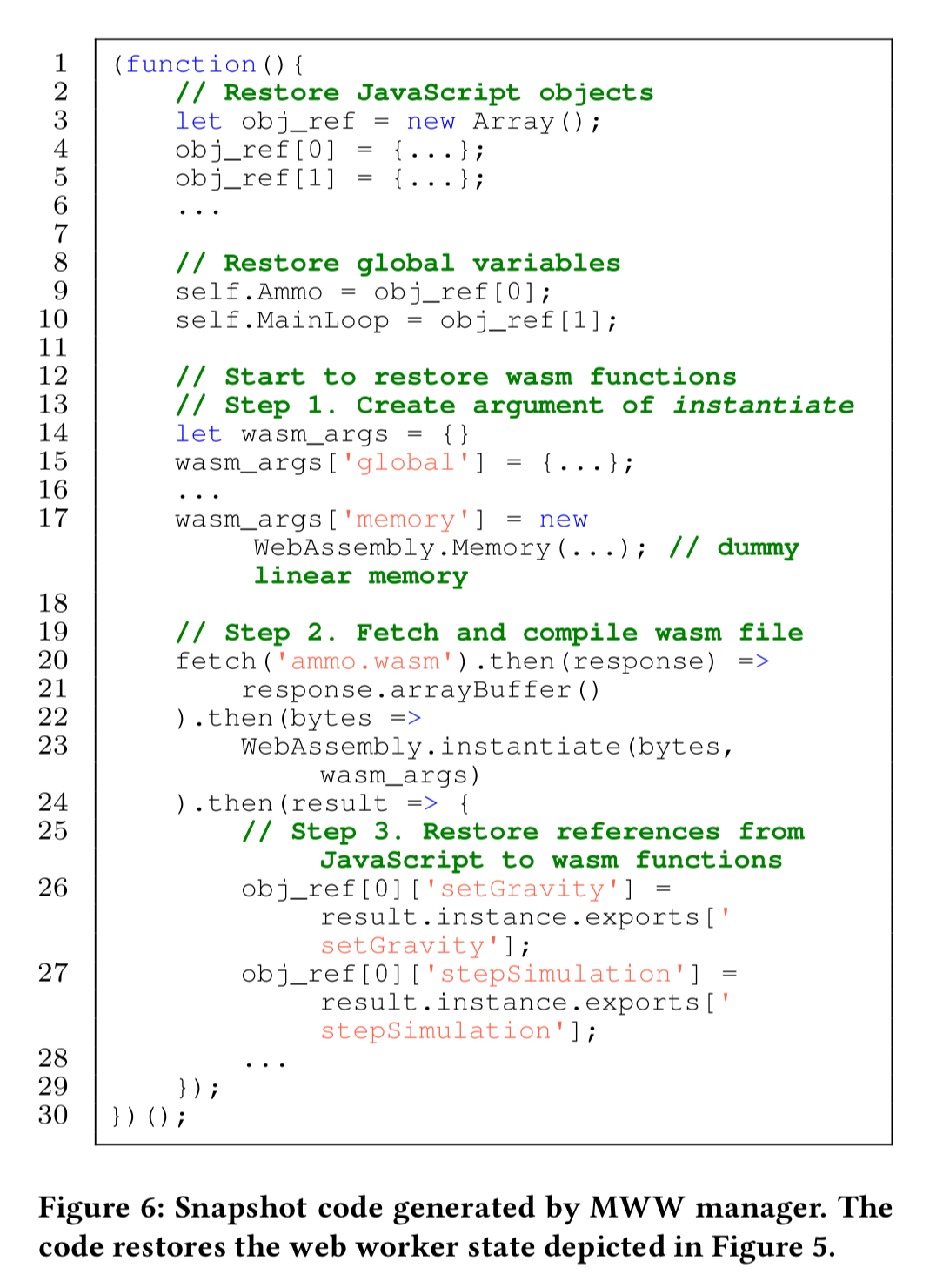

Central to worker migration is the ability to take a snapshot of the current worker state – which can include a mix of JavaScript objects, web assembly functions, and native built-in objects. As an example, the figure below illustrates the runtime state of the cubes simulation app.

Capturing JavaScript can be done via traversal of variables in the worker global scope, but web assembly functions are a bit more involved.

Wasm functions contain native codes compiled at runtime, so they should not be directly migrated as normal JavaScript objects. For example, if we send wasm functions compiled at at ARM client to an x86 server, the wasm functions will not run properly.

Beyond snapshotting, we also need to figure out when and where to migrate workers to. Since we’re talking about mobile applications, we have to assume a changing environment over time, including the possibility of losing internet connectivity altogether.

The Mobile Web Worker (MWW) System

The Mobile Web Worker (MWW) System introduces a new client-side Mobile Web Worker Manager component which is responsible for managing web workers, including their migration when this is estimated to be beneficial. On the server side (in the edge or cloud) another Mobile Web Worker Manager component is responsible for managing pools of mobile workers.

The current system assumes an application specific regression model is available on the servers which can predict processing time given the current parameters of the job (e.g. the number of cubes to be rendered in the physics simulation). The MWW manager on the client sends a query to all nearby edge servers including the input size of the worker. These use their regression models to estimate processing time (which will depend on the hardware available, current load, etc.). The client MWW combines these estimates with an estimate of the input/output transmission time (latency) to find the worker with the minimum overall execution latency. This could of course be a local worker on the mobile device. The location selection algorithm is run periodically to see if better options are now available.

If the client is disconnected from an edge server to which one of its workers has migrated, then that worker is further migrated to a pre-determined fallback server with stable connectivity (e.g., in the cloud). The idea is that the client should be able to reconnect to its worker from there wherever the client has moved to in the meantime. If the client can’t even access the fallback server (e.g., due to total loss of internet connectivity) then the worker needs to be restarted. If loss of connectivity can be predicted ahead of time, then the worker can be migrated back to the client in advance of connectivity loss.

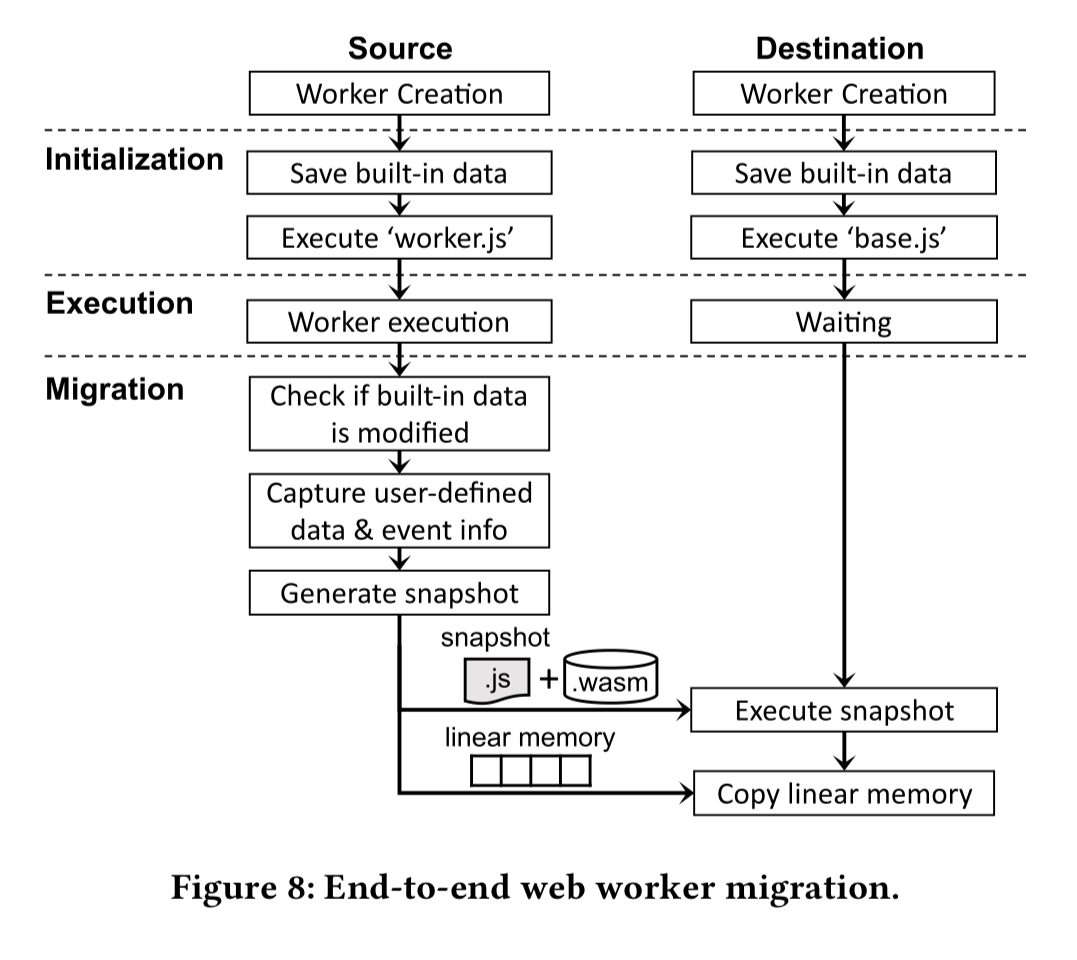

The end-to-end migration process looks like this:

In the edge server ("Destination") in the figure above, pre-built workers are on standby, waiting to receive a snapshot and copy of any wasm-backing linear memory in order to take over from a given client worker. To speed up migration and quickly restore wasm functions at the destination, the wasm instantiate function is intially called with a dummy linear memory, and then this is later replaced once the real memory has arrived over the network.

For each application, a custom JavaScript function is generated which will capture and restore all the necessary state. An example for the cubes application is shown below.

Move it! – MWWF in action

The MWW System prototype is implemented in Chrome for the browser, and Node.js for the edge and cloud execution environments. It requires about 200 lines of modified platform code in each case, with the rest of the MWW System being implemented in pure JavaScript. Three tests applications are used to evaluate the platform: the physics simulation (cubes) application we saw earlier, an OpenCV face detection application, and an image filtering application which applies a Gaussian blur to an input image.

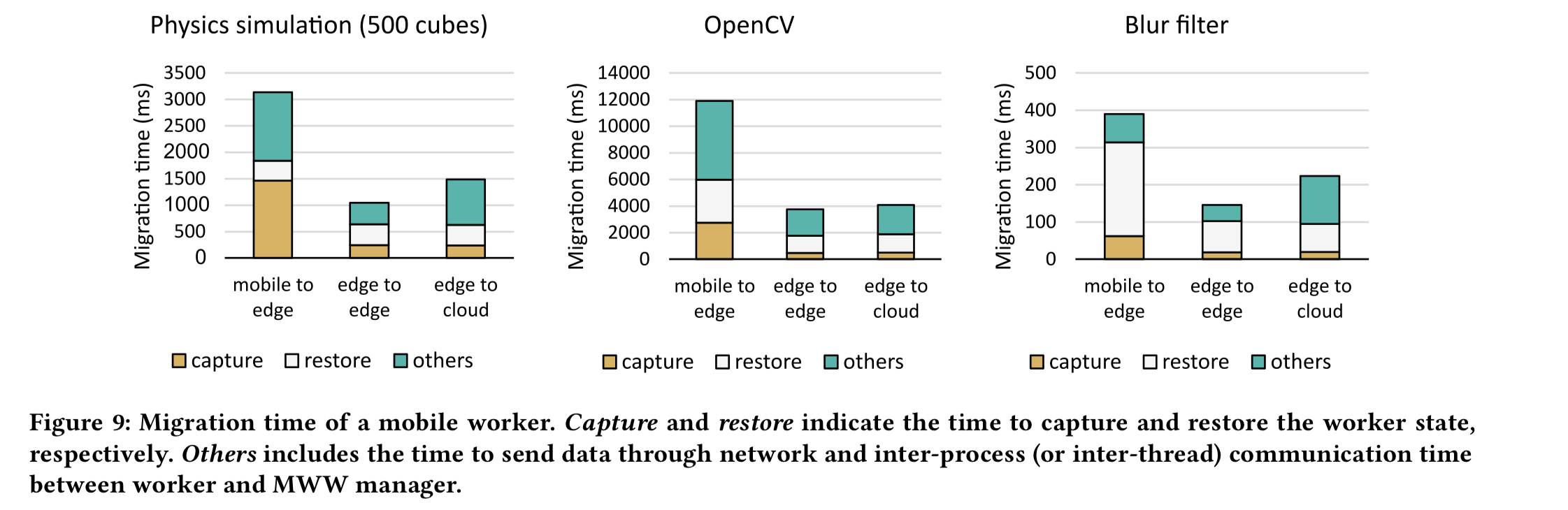

The figure below shows the migration time for these three applications, broken down into snapshot capture, snapshot restoration, and ‘other’ (including the network transfer time). The different applications have quite different profiles in terms of their snapshot size, linear memory size, and wasm source file size. The opencv app has the largest state (4.6 MB snapshot, 128 MB memory, and 5.9 MB of wasm), filter is the smallest (77 KB snapshot, 16 MB memory, and 34 KB of wasm). For these results, upload and download speed for mobile client to edge was set at 10 Mbs and 36 Mbps respectively, and for edge-to-edge and edge-to-cloud 42 Mbps and 118 Mbps respectively.

Given the large sizes involved, opencv takes the longest to migrate (3.8-11.9 seconds), meanwhile cubes can migrate in 1-3 seconds, and the blur filter is on the order of a few hundred ms.

Is the migration worth it though? The following figure shows the application performance achieved for both JavaScript and Web Assembly versions of the worker code when running on the client device (local), and on the edge server (offload). For comparison, the server bar also shows performance when the full application runs on the server.

In the physics app edge processing yields 1.6x more fps for the JavaScript version, and 1.9x for the wasm-version. For the face recognition app, the biggest boost comes from using wasm instead of JavaScript. Offloading wasm workers to the edge server yields a further 2.6x over running the workers on the mobile device. For the filter app the JavaScript version sees a 2.4x improvement, and the wasm version a 1.4x (here the compute speed-up is offset by the long transmission time to send the input/output images).

Up next

Future work includes delving into more realistic use cases and addressing other challenges related to mobile computing such as energy efficiency. Integration with outer edge computing techniques is also of strong interest. For example, we can adapt modile workers to serverless edge computing to support offloading of stateful computations without external storage…

[^1]: Accessing this paper from this blog post should grant you access to this paper in the ACM Digital Library – thank you ACM!

15 thoughts on “Seamless offloading of web app computations from mobile device to edge clouds via HTML5 Web Worker migration”

Comments are closed.