Declarative assembly of web applications from predefined concepts De Rosso et al., Onward! 2019

I chose this paper to challenge my own thinking. I’m not really a fan of low-code / no-code / just drag-and-drop-from-our-catalogue forms of application development. My fear is that all too often it’s like jumping on a motorbike and tearing off at great speed (rapid initial progress), only to ride around a bend and find a brick wall across the road in front of you. That doesn’t normally end well. I’ve seen enough generations of CASE (remember that acronym?), component-based software development, reusable software catalogues etc. to develop a healthy scepticism: lowest-common denominators, awkward or missing round-tripping behaviour, terrible debugging experiences, catalogues full of junk components, inability to accommodate custom behaviours not foreseen by the framework/component developers, limited reuse opportunities in practice compared to theory, and so on.

The thing is, on one level I know that I’m wrong. To start with, there’s Grady Booch’s observation that “the whole history of computer science is one of ever rising levels of abstraction” 1. Then there’s the changing demographic of software building. Heather Miller recently gave a great presentation on this topic, ‘The times they are a changin’‘. To quote from her presentation:

There’s a tidal wave of newcomers entering our profession, and it’s not going to slow down. It’s going to pick up speed. – Heather Miller.

We’re also doing a pretty good job at reuse, and messy catalogues full of junk components don’t actually seem to be a problem in practice, so long as the ‘good stuff’ is readily identifiable (think package managers / ‘there’s a gem for that’). Another data point from Miller’s presentation: in 2018 57-70% of the average software project comprises open source components, and that fraction is rising fast. “We largely glue together open source components now (we didn’t do this as much, not even like 3 years ago).”

As a final data point, low-code companies have been able to build sizeable businesses, e.g. Appian valued at $2.89B as I write, and Mendix acquired by Siemens for $700M in 2018.

So, it’s important on a number of levels to keep pushing on rising the level of abstraction. For me, the winning hand will have to combine both technical and social frameworks – supporting, encouraging, and growing a healthy ecosystem is a necessary ingredient of success here.

The paper!

Onto the paper! Let’s find out what De Rosso et al, have to say about the ‘Declarative assembly of web applications from predefined concepts.’

A new approach to web application development is presented, in which an application is constructed by configuring and composing concepts drawn from a catalog developed by experts.

The platform (framework) for building these applications is called Déjà Vu, and the unit of abstraction in Déjà Vu is a Concept. Concepts are more closely aligned with application features than with e.g. class-level components. Examples are commenting, scoring, and so on. Concepts are embodied as microservices:

A Déjà Vu application is a set of concept instances that run in parallel. Each instance is a full stack service in its own right, with front-end GUI components, a back-end server and data storage, and all the code necessary to coordinate them. By default these services run entirely independently of one another, in complete isolation.

I’ve called them microservices here, but the authors are at pains to point out that concepts are more fine-grained that traditional plug-ins or microservices.

Abstractly, a concept instance is a state machine that changes state only in response to actions issued by the user through the front-end.

A bit like actors-with-front-ends then? And surely we’d want to generalise to event sourcing patterns where not all events have to originate in a user action?

The integration of two or more concepts is achieved by defining a common identifier to bind the distinct views. That’s going to present challenges with atomic changes across concepts. The more fine-grained your ~components~ concepts are, the more that matters. The authors include a transaction mechanism, but it’s not clear to me how it coordinates updates across the independent concept backends.

What’s new in this work is what the parts are — full-stack implementations of concepts — and how they are put together — by declarative synchronization.

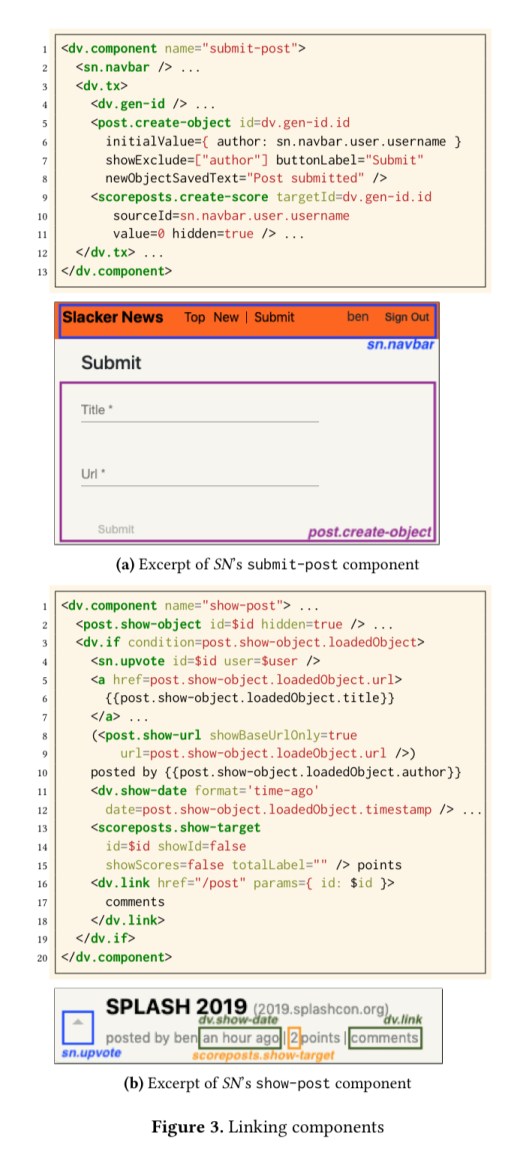

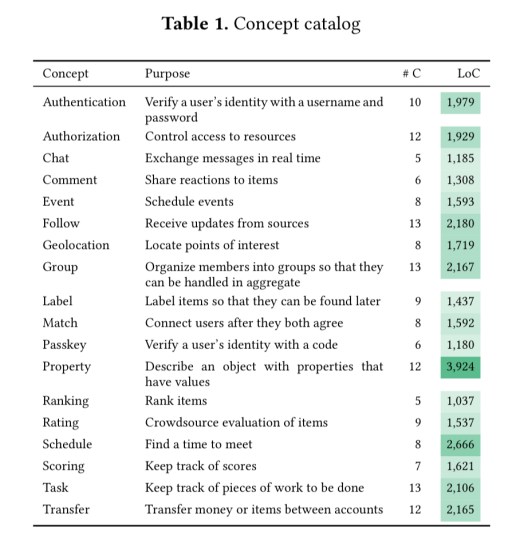

Here’s an example configuration file for a Hacker News clone called Slacker News.

Alongside pre-defined concepts, an application may include components of its own. Authoring application components involves the creation of a web component using a templating language for property binding. Application components may in turn be composed of other application components and concepts.

A key distinction between application components and concepts is that application components are front-end only, all back-end functionality is pushed to concepts. (Make those concept instances shared across apps, and it starts to look a lot like a back-end-as-a-service play…).

The special tx application component is used to wrap concept actions (across concepts) in a transaction. When every concept is its own independent full-stack implementation, we’re going to need each concept back-end to be able to act as a resource manager in a distributed transaction for this to work? The paper is silent on this issue.

Déjà Vu in action

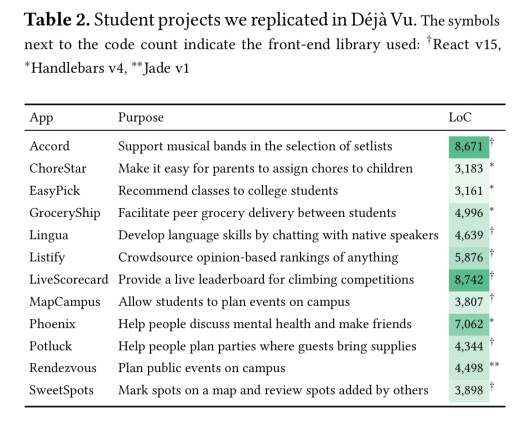

There’s a bit more detail about the Déjà Vu programming model in the paper, but not much. The prototype implementation is built in TypeScript, Angular, and Node.js, and includes a concept library with the following concepts:

There are both monolith (all concept backends in a single Node.js app?) and microservice based backends. So I guess we should infer that concepts are logically independent, but can be physically deployed in the same app and fate-sharing.

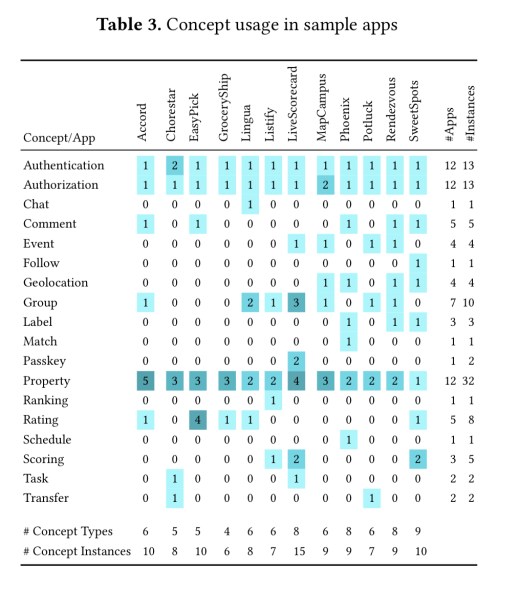

To test building applications using Déjà Vu, the authors attempted to reproduce 12 student applications originally created as part of a Fall’16 undergraduate course.

The median number of concept types used to implement the apps was 6, with a median of 9 concept instances (some apps use multiple instances of a concept).

The original projects each represented 200-400 person-hours of work. I was looking for some data to see how much effort it took to rebuild these projects with Déjà Vu, but couldn’t find it in the paper. Instead the main evaluation results seem to focus on the fact that it was possible.

The old chestnut of behaviour not foreseen by the framework / component developer raises its head, with a classic framework developer response too!

We noticed that it becomes evident when some project deviates from what you’d expect the normal behavior of certain functionality to be… it raises an interesting research question — which we have yet to explore — about whether deviations from the norm (where “norm” is functionality that can be built by combining concepts Déjà Vu-style) represent design flaws in the application or the invention of a novel concept.

Yep, you read that right. If the thing you’re trying to build doesn’t fit with our framework, you probably have a design flaw!

Another classic question concerns the curation and evolution of the concept catalog. Is this an open repository that will gradually fill up with noise, or a carefully curated catalog — in which case who curates it and how does this scale?

To avoid overlapping functionality between concepts, we only add a new concept to the catalog if there is no other concept with a similar purpose, and we only add functionality to a concept if such functionality cannot be obtained by combining the concept with other concepts. But having simpler and more orthogonal concepts can mean more work combining them.

Future work for Déjà Vu includes building a graphical programming environment to allow developers to build applications without explicitly having to write any binding or configuration code.

I still have nearly all the questions I started this piece with. At the same time, by engaging with the paper and the topic I’m getting clearer in my own mind as to what my requirements for a future application composition system would be. To quote Grady Booch one more time: “the whole history of computer science is one of ever rising levels of abstraction.”

- You’ll find lots of variations of this quote on the web, but this is the one that has stuck in my mind from 15+ years ago when I first heard Grady Booch say it. ↩

Hi, nice blog post! Interesting to read your take on this. It seems like an interesting language, this Deja Vu, although the concepts seem to me to be of different abstraction levels. I would like to recommend you to have a look at our Alan Platform (https://alan-platform.com) as well. It shares some of the characteristics of Deja Vu, but at a more abstract level. We were able to build Alan with Alan, for instance. But we also built ERP and MES systems with it, that have been in use for several years now. Regards, Rick

To me the real problem is competition from libraries and getting-started code generators, not that low code is bad.

i.e. why choose low code (which 95% of the time you’ll have to rewrite) when for x% more effort, you can have the real thing.

Over time, this struggle goes back and forth – some years the low code systems win because there’s not enough innovation happening, other years they’re a joke.

Finally, you’ll never choose a low code framework for a major app used by millions of people – because the cost savings is deminimus vs other costs to promote and operate the app. Going the other way, you’ll always try to use a low code framework for internal apps used by a tiny number of people.

This sounds like the eventual goal of every Content Management System out there (including the 5 I’ve worked on personally), and, as you conclude, they seem to be stuck at the exact same place everyone else is…

Hi Adrian, I am the first author of the paper. Thank you so much for reviewing our paper. It was very interesting to read your thoughts on it. Some comments:

> The authors include a transaction mechanism, but it’s not clear to me how it coordinates updates across the independent concept backends.

We run a two phase commit between the independent concept backends. How we do this is explained in more detail in section 3.2. In a nutshell, all requests go through a gateway which, in the case of a transaction request, acts a transaction coordinator and runs a two phase commit between the concept backends.

> When every concept is its own independent full-stack implementation, we’re going to need each concept back-end to be able to act as a resource manager in a distributed transaction for this to work? The paper is silent on this issue.

Yes, each concept backend is essentially a resource manager in a distributed transaction.

> There are both monolith (all concept backends in a single Node.js app?) and microservice based backends. So I guess we should infer that concepts are logically independent, but can be physically deployed in the same app and fate-sharing.

Yes, each concept backend runs as a different program and you can co-locate them on the same physical machine if you want to. Concepts are not multi-tenant: each Déjà Vu application has its own

set of concept instances, even if they share the same concepts.

> I was looking for some data to see how much effort it took to rebuild these projects with Déjà Vu, but couldn’t find it in the paper.

This is not in the paper, but we recently did an effort comparison using lines of code and we found that using Déjà Vu to build the 12 applications of our case study resulted in 18% less code than the student implementations. I’ll be publishing this analysis soon and I’ll update this comment with a link when I have one.

> Yep, you read that right. If the thing you’re trying to build doesn’t fit with our framework, you probably have a design flaw!

We are not saying all of the functionality that doesn’t fit with our framework is necessarily a design flaw. There might be a perfectly valid reason to implement what looks like a rather anomalous concept, but it should make you pause and think more about whether it is actually the right thing to do. For example, perhaps the functionality belongs to some other concept.

> I still have nearly all the questions I started this piece with.

What questions did you start with?