Machine learning systems are stuck in a rut Barham & Isard, HotOS’19

In this paper we argue that systems for numerical computing are stuck in a local basin of performance and programmability. Systems researchers are doing an excellent job improving the performance of 5-year old benchmarks, but gradually making it harder to explore innovative machine learning research ideas.

The thrust of the argument is that there’s a chain of inter-linked assumptions / dependencies from the hardware all the way to the programming model, and any time you step outside of the mainstream it’s sufficiently hard to get acceptable performance that researchers are discouraged from doing so.

Take a simple example: it would be really nice if we could have named dimensions instead of always having to work with indices.

Named dimensions improve readability by making it easier to determine how dimensions in the code correspond to the semantic dimensions described in, .e.g., a research paper. We believe their impact could be even greater in improving code modularity, as named dimensions would enable a language to move away from fixing an order on the dimensions of a given tensor, which in turn would make function lifting more convenient…

For the readability point I feel I ought to mention you could always declare a ‘constant’ , e.g FEATURE_NAME = 1, and use that to make your code more readable (constant is in quotes there because Python doesn’t really have constants, but it still has variable names!). But that won’t solve the ordering issue of course.

It would be interesting to explore unordered sets of named dimensions in the programming model and see what benefits that could bring, however,…

It is hard to experiment with front-end features like named dimensions, because it is painful to match them to back ends that expect calls to monolithic kernels with fixed layout. On the other hand, there is little incentive to build high quality back ends that support other features, because all the front ends currently work in terms of monolithic operators.

Named dimensions are an easy to understand example, but the challenges go much deeper than that, and were keenly felt by the authors during research on Capsule networks.

Challenges compiling non-standard kernels

Convolutional Capsule primitives can be implemented reasonably efficiently on CPU but problems arise on accelerators (e.g. GPU and TPU). Performance on accelerators matters because almost all current machine learning research, and most training of production models, uses them.

Scheduling instructions for good performance in accelerators is a complex business. It’s “very challenging” just for standard convolutions, and convolutional capsules add several dimensions of complexity. Because it’s so tricky, high-performance back-ends for accelerators tend to spend a lot of effort optimising a small set of computational kernels.

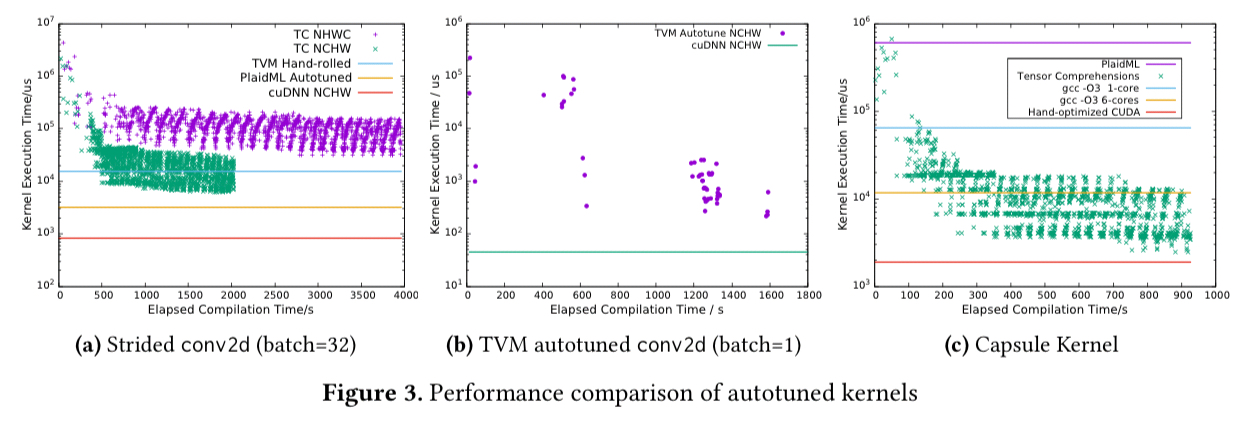

New primitives that don’t fit into these existing kernels can be compiled into custom kernels using e.g. Tensor Comprehensions or PlaidML, but the current state-of-the-art only really supports small code fragments and frequently doesn’t get close to peak performance (e.g. a factor of 8x slower after a one hour search, for a conventional 2D convolution the authors used as an experiment).

Our interpretation of these results is that current frameworks excel at workloads where it makes sense to manually tune the small set of computations used by a particular model or family of models. Unfortunately, frameworks become poorly suited to research, because there is a performance cliff when experimenting with computations that haven’t previously been identified as important.

That said, after around 17 minutes Tensor Comprehensions does find a solution that outperforms a hand-tuned CUDA solution. Which doesn’t seem so bad, until you remember this is just one kernel out of what may be a large overall computation.

The easiest and best performing solution for convolutional Capsules in both TensorFlow and PyTorch turns out to be to target high-level operations already supported by those frameworks. This comes at a cost though; copying, rearranging, and materialising to memory two orders of magnitude more data than is strictly necessary.

Challenges optimising whole programs

It might be hard to performance tune a single non-standard kernel, but full programs must typically evaluate a large graph of kernels. In order to make use of pre-optimised kernels, it’s necessary to use one of a small number of parameter layouts that have been chosen ahead of time to be optimal in isolation.

In practice there are so few choices of layout available that frameworks like XLA and TVM do not attempt a global layout assignment, and instead choose fixed layouts for expensive operators like convolution, then propagate those layouts locally through the operator graph inserting transposes where necessary.

Similar considerations make it hard to experiment with different choices for quantised and low-precision types.

Whole program optimisations such as common sub-expression elimination are attractive for machine learning, but hard to exploit to the fullest extent with the current state-of-the-art: “it seems likely that it will be necessary to architect machine learning frameworks with automatic optimizers in mind before it will be possible to make the best use of whole-program optimization.“

Challenges evolving programming languages

Recall that back ends are structured around calls to large monolithic kernels. In this section we argue that this back-end design approach is slowing progress in the maintainability, debuggability, and expressiveness of programming models. Worse, the resulting brake on innovation in languages is in itself reducing the incentive for back-end developers to improve on the current situation.

We saw one such example at the top of this piece: support for named dimensions. Another consequence is the choice of kernels or ‘operators’ as the dominant abstraction, with user programs in Python calling into operators written in terms of specific back-end languages and libraries. This tends to fix both the set of operators and also their interfaces.

Breaking out of the rut

Our main concern is that the inflexibility of languages and back ends is a real brake on innovative research, that risks slowing progress in this very active field…

How might we break out of the rut?

- Embrace language design including automatic differentiation, using purely named dimensions and kernels expressed within the language syntax

- Support a back-end IR defining a graph of layout-agnostic general purpose loop nests

- Use transformation passes over the IR to lower it to a concrete common sub-expression elimination strategy, with layouts for each materialised intermediate

- Compilation passes that generate accelerator code given the lowered IR, with adequate code produced quickly and close to peak performance achievable after searching

At a high level, this reminds me a little of the approach taken by Musketeer.

https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0591/

You touched on data and feature engineering a little bit when talking about named features but I think it’s a huge elephant in the room. Managing, organizing, and building features on top of data right now is a black art while most of the efforts are focussed on building models instead of systems that feed the models. An analogy is that we focus too much on the brain vs sight, sound, touch and smell, which is clear that without those the brain is useless.

It reminds me more of the Zygote project, bringing fully differentiable programming to Julia. https://github.com/FluxML/Zygote.jl

This reads like an advertisement for the Julia programming language, except that punchline never came.

Libraries that implement automatic differentiation (Zygote.jl and others) and provide purely named dimensions (NamedArrays.jl, AxisArrays.jl) can be used together. CUDA kernels can be expressed within the language syntax with CUDAnative.jl

The language exposes IR for manipulation and has a very LISP-like metaprogramming feel to it; see for example how Zygote.jl uses IRTools.jl to do source-to-source auto diff.

Of course it doesn’t have the same traction as python. Traction takes time, but it’s building up…

Stumbled across this while browsing my news feeds today. May be worth a follow up on this post? http://lambda-the-ultimate.org/tensor-considered-harmful