Towards a design philosophy for interoperable blockchain systems Hardjono et al., arXiv 2018

Once upon a time there were networks and inter-networking, which let carefully managed groups of computers talk to each other. Then with a capital “I” came the Internet, with design principles that ultimately enabled devices all over the world to interoperate. Like many other people, I have often thought about the parallels between networks and blockchains, between the Internet, and something we might call ‘the Blockchain’ (capital ‘B’). In today’s paper choice, Hardjono et al. explore this relationship, seeing what we can learn from the design principles of the Internet, and what it might take to create an interoperable blockchain infrastructure. Some of these lessons are embodied in the MIT Tradecoin project.

We argue that if blockchain technology seeks to be a fundamental component of the future global distributed network of commerce and value, then its architecture must also satisfy the same fundamental goals of the Internet architecture.

The design philosophy of the Internet

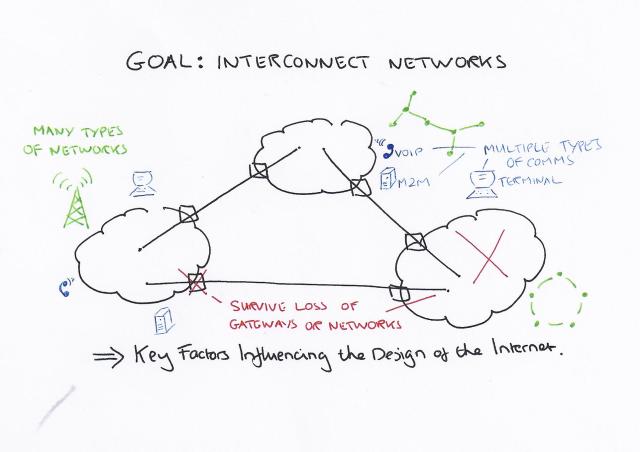

This section of the paper is a précis of ‘The design philosophy of the DARPA Internet protocols’ from SIGCOMM 1988. The top three fundamental goals for the Internet as conceived by DARPA at that time were:

- Survivability: Internet communications must continue even if individual networks or gateways were lost

- The ability to support multiple types of communication service (with differing speed, latency, and reliability requirements).

- The ability to accommodate and incorporate a variety of networks

In addition, the end-to-end principle was central in deciding where responsibility for functionality should lie: in the network versus in the applications at the network endpoints. A classic example is end-to-end encryption, which needs to be between the communicating parties and therefore places responsibility for this with the endpoints.

The Internet is structured as a collection of autonomous systems (routing domains), stitched together through peering agreements. Autonomous Systems (ASs) are owned and operated by legal entities. All routers and related devices are uniquely identified within a domain. Interaction across domains is via gateways (using e.g. BGP).

A design philosophy for the Blockchain

We believe the issue of survivability to be as important as that of privacy and security. As such, we believe that interoperability across blockchain systems will be a core requirement — both at the mechanical level and the value level — if blockchain systems and technologies are to become fundamental infrastructure components of future global commerce.

An interoperable blockchain architecture as defined by the authors has the following characteristics:

- It is composed of distinguishable blockchain systems, each representing a distributed data ledger

- Transaction execution may span multiple blockchain systems

- Data recorded in one blockchain is reachable and verifiable by another possible foreign transaction in a semantically compatible manner

Survivability is defined in terms of application level transactions: it should still be possible to complete a transaction even when parts of The Blockchain are damaged.

The application level transaction may be composed of multiple ledger-level transactions (sub-transaction) and which may be intended for multiple distinct blockchain systems (e.g. sub-transaction for asset transfer, simultaneously with sub-transaction for payments and sub-transaction for taxes).

(Are we reinventing XA all over again?)

Sub-transactions confirmed on a spread of blockchain systems are opaque to the user application, in the same way that packets routing through multiple domains is opaque to a communications application.

The notions of survivability and blockchain substitution in the event of failure raise a number of questions such as the degree to which an application needs to be aware of individual blockchain systems’ capabilities and constructs, and where responsibility for reliability (e.g. re-transmitting a transaction) should lie. What should we do about resident smart contracts that exist on a (possibly unreachable) blockchain system, and hence may not be invokable or able to complete? Can smart contracts be moved across chains? Should the current chain on which a contract resides be opaque to applications (i.e., give it an “IP” address which works across the whole Blockchain)? How do we know when to trigger the moving of a contract from one chain to another?

The Internet goal of supporting multiple types of service with differing requirements is reinterpreted as need to support multiple types of chain with differing consensus, throughput, and latency characteristics. (And we might also add security and privacy to that list).

When it comes to accommodating multiple different blockchain systems, we want to be able to support transactions spanning blockchains operated (or owned) by different entities. In the Internet, the minimum assumption is that each network must be able to transport a datagram or packet as the lowest unit common denominator. What is the corresponding minimum assumption for blockchains? How can data be referenced across chains? What combinations of anonymity (for users and for nodes) can be supported?

The notion of value is at a layer above blockchain transactions (just as the Internet separates the mechanical transmission of packets from the value of the information contained in those packets). For families of applications that need to transfer value across chains, the Inter-Ledger Protocol offers a promising direction.

Tradecoin

The MIT Tradecoin project has a number of objectives, one core goal being the development of a “blueprint” model for interoperable blockchain systems which can be applied to multiple use cases.

Ultimately there are two different levels of interoperability: mechanical level interoperability, and value level interoperability (encompassing constructs that accord value as perceived in the human world). “Humans, societies, real assets, fiat currencies, liquidity, legal regimes and regulations all contribute to form the notion of value as attached to (bound to) the constructs (e.g., coins, tokens) that circulate in the blockchain system….” The two level view follows the end-to-end principle by placing the human semantics (value) at the ends of (outside) the mechanical systems.

Legal trust is the contract that binds the technical roots of trust at the mechanical level with legally enforceable obligations and warranties.

Legal trust is the bridge between the mechanical level and the value level. That is, technical-trust and legal-trust support business trust (at the value level) by supporting real-world participants in quantifying and managing risks associated with transactions occurring at the mechanical level. Standardization of technologies that implement technical trust promotes the standardization of legal contracts — also known as legal trust frameworks — which in turn reduces the overall business cost of operating autonomous systems.

(And not only that, it provides the trust required for businesses to trade value on blockchains).

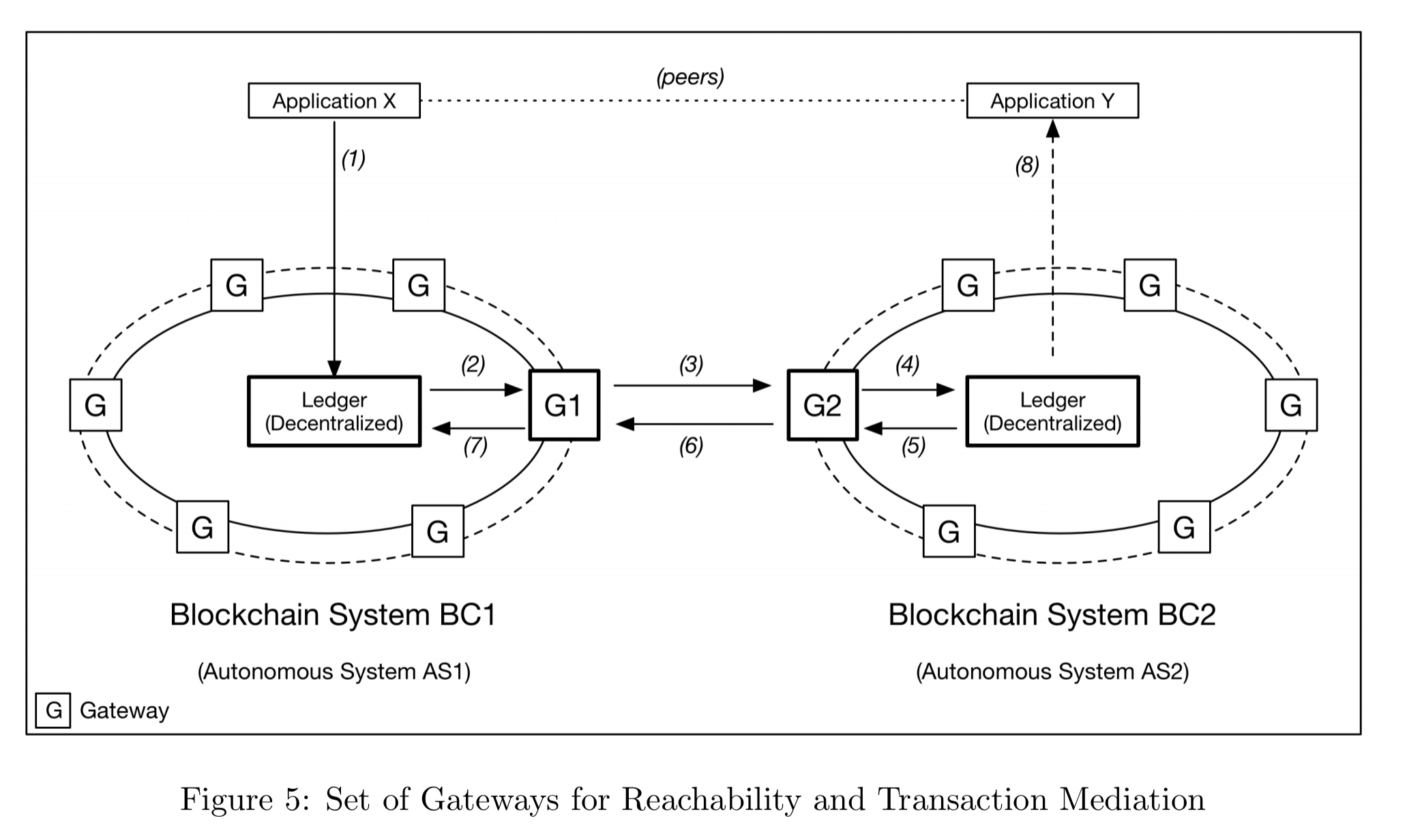

Tradecoin views individual blockchain systems as fully autonomous, and connects them via gateways. Gateways provide value stability, reachability, and transaction mediation for cross-domain transactions.

To support reachability, gateways resolve identifiers and may provide a NAT-like function to translate between internal and external identifiers. When it comes to transaction mediation, the Tradecoin view seems to be that gateways will act as transaction coordinators, with individual blockchain systems acting as resource managers.

Since blockchains BC1 and BC2 are permissioned and one side cannot see the ledger at the other side, the gateways of each blockchain must “vouch” that the transaction has been confirmed on the respective ledgers. That is, the gateways must issue legally-binding signed assertions that make them liable for misreporting (intentionally or otherwise). The signature can be issued by one gateway only, or it can be a collective group signature of all gateways in the blockchain system.

For all this to work smoothly, there are five ‘desirable features’:

- Both the transaction initiating and recipient applications must be able to independently verify that the transaction was confirmed on their respective blockchains.

- Gateway signatures must be binding, regardless of the gateway selection mechanism used.

- There should be multiple reliable ‘paths’ (sets of gateways) between any two blockchains.

- There must be a global resolution mechanism for identifiers such that they can always be resolved to the correct authoritative blockchain system.

- Gateways must all be identifiable (i.e., not anonymous), both within and across domains. “Gateways must be able to mutually authenticate each other without any ambiguity as to their identity, legal ownership, or the ‘home’ blockchain autonomous system which they exclusively represent.“

Gateways are connected together via the equivalent of peering agreements:

For the interoperability of blockchain systems, a notion similar to peering and peering-agreements must be developed that (i) defines the semantic compatibility required for two blockchains to exchange cross-domain transactions; (ii) specifies the cross-domain protocols required; (iii) specifies the delegation and technical-trust mechanisms to be used; and (iv) defines the legal agreements (e.g. service levels, fees, penalties, liabilities, warranties) for peering. It is important to note that in the Tradecoin interoperability model, the gateways of a blockchain system represent the peering-points of the blockchain.

Requirement (iv) above seems problematic in cases where there is no well-defined legal entity associated with a blockchain.

“Interoperability forces a deeper re-thinking into how permissioned and permissionless blockchain systems can interoperate without a third party (such as an exchange).“

Hello there, I can see that these ideas are working with BCs like BTC and maybe ETHER. But, like it was very well explained in the IBM HyperLedger Fabric Tutorials, those BCs are public in transactions and anonymous in the participants – which may be just the opposite in business networks. So how will those contradictive BC families be connected?

Hi Adrian,

I hope this message finds you well.

This is Ajian, from Ethfans.org, which is a China based Ethereum developer community, dedicating to promoting Ethereum and blockchain technology in China. One of our main projects is translating selected English posts into Chinese and circulating them on our website and newsletters, where we have more than 4000 daily visits.

I am wondering if we can ask your authorization to translate this post for non-profit purpose. If permitted, the Chinese version will be posted on ethfans.org and our wechat daily newsletter. We will specify your authorship of the post, and put down a link to your original post.

Please let me know if you have other requirements regarding the authorization. Looking forward to your reply.

Thank you.

Best regards,

Ajian

Hi Aijan, you are very welcome to translate the post. Thank you for your interest!

Thank you very much! When I have done I will send you a link!

Hi Adrian, we have translated your post into Chinese and republished it on this page:

Thanks very much! Welcome to connect with me if there is anything we can help you!