The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world Kurtz & Snowden et al., IBM Systems Journal, 2003

Tomorrow we’ll be taking a look at a paper recommended by Linda Rising during her keynote at GOTO Copenhagen earlier this month. Today’s choice provides the necessary background to the Cynefin (Kin-eh-vun) framework on which it is based. If I had to summarise Cynefin in one sentence I think it is this: one size does not fit all. And following that, I value the insight that sometimes we operate in domains where there isn’t a straightforward linear cause-and-effect relationship, although we like to act as though there is!

In addition to the paper, I found watching Dave Snowden’s keynote talk “Embrace Complexity, Scale Agility” (on YouTube) to be helpful.

The development of management science, from stop-watch-carrying Taylorists to business process reengineering, was rooted in the belief that systems were ordered; it was just a matter of time and resources before the relationships between cause and effect could be discovered… All of these approaches and perceptions do not accept that there are situations in which the lack of order is not a matter of poor investigation, inadequate resources, or lack of understanding, but is a priori the case — and not necessarily a bad thing, either.

Things we believe to be true that ain’t necessarily so

- There are underlying relationships between cause and effect in human interactions and markets, which are capable of discovery and empirical validation. Under this assumption, an understanding of casual links in past behaviour enables us to define best practice for future behaviour. There is a right or ideal way of doing things.

- Faced with a choice between one or more alternatives, human actors will make a rational decision. Under this assumption, individual and collective behaviour can be managed by manipulation of pain or pleasure outcomes, and through education to make those consequences evident.

- The acquisition of capability indicates an intention to use that capability. “We accept that we do things by accident, but assume that others do things deliberately.”

…although these assumptions are true within some contexts, they are not universally true … we are increasingly coming to deal with situations where these assumptions are not true, but the tools and techniques which are commonly available assume that they are.

Order and Un-order

There is order which we design and control, and there is also emergent order which can arise through the interaction of many entities. We looked at some emergent order based algorithms on The Morning Paper back in September 2015. This emergent order is still order, but of a different kind. In the paper, the authors call it ‘un-order’, in the spirit of the word ‘undead’. It Neither ordered in the traditional senses, nor disordered, but somewhere in-between.

… learning to recognize and appreciate the domain of un-order is liberating, because we can stop applying methods designed for order and instead focus on legitimate methods that work well in un-ordered situations.

In the world of the un-ordered, every intervention is also a diagnostic, and every diagnostic an intervention – any act changes the nature of the system.

The Cynefin framework

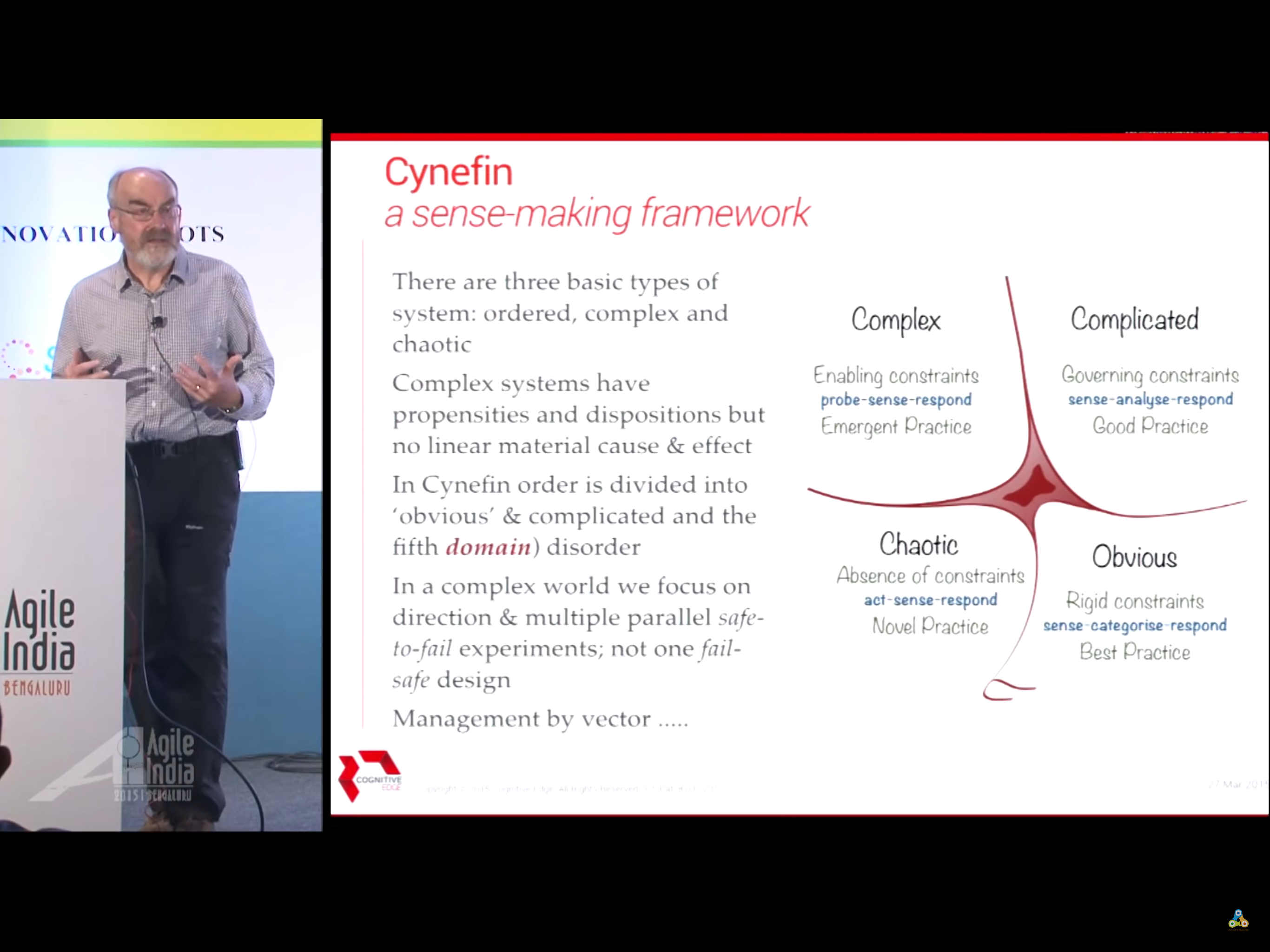

The Welsh word Cynefin has no direct translation into English, but seems to convey a deep sense of place. The Cynefin framework is designed to help you make sense of a situation and think about it in new ways. It looks a bit like a quadrant, but the authors are at pains to point out (a) there are five domains (including the area of disorder in the centre), and (b) there is no-one domain that is better than the others – this is not about trying to get to the top-right corner!

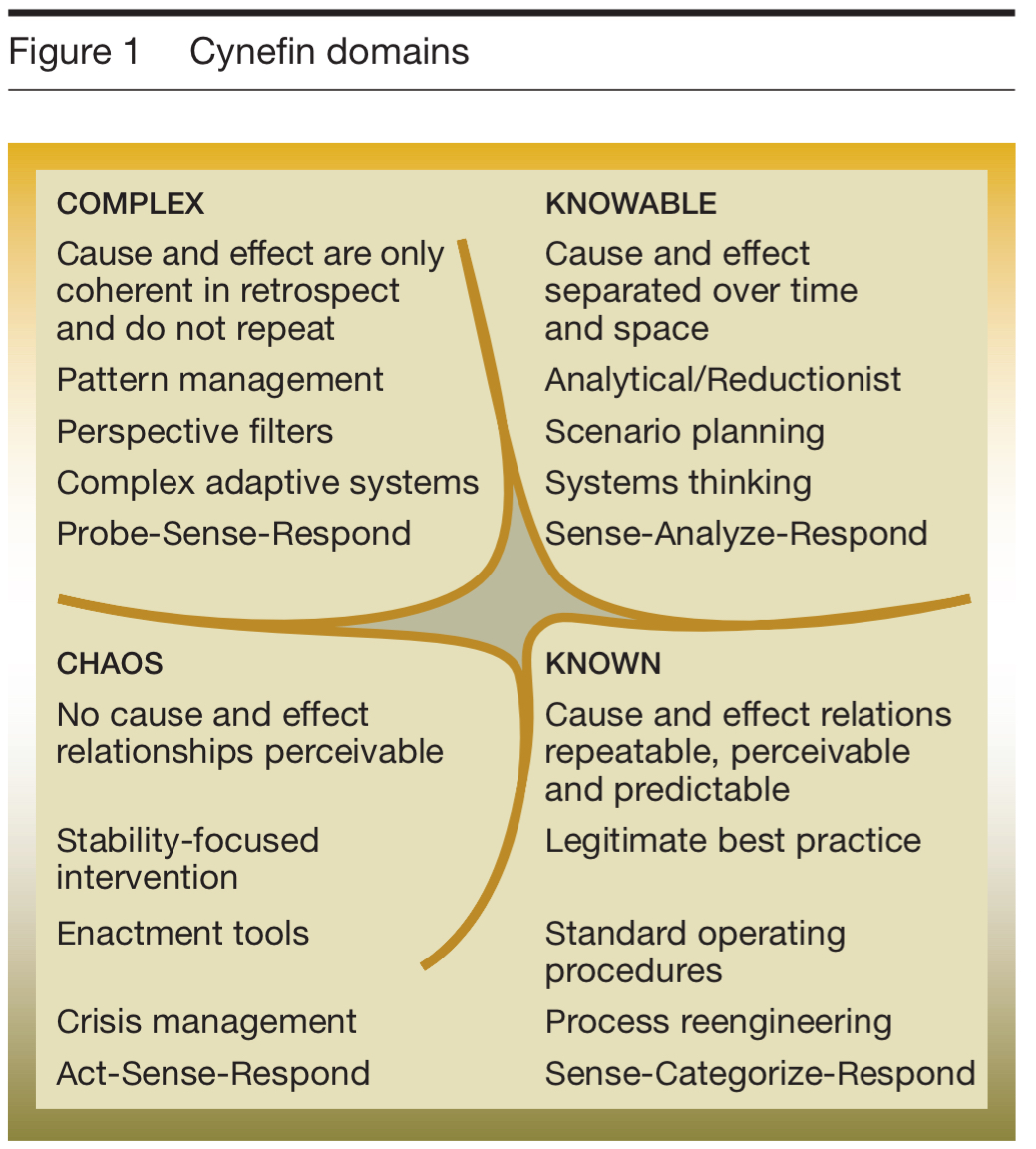

On the right-hand side we have ordered domains, and on the left-hand side are the un-ordered domains. In the middle is disorder. As of 2003, the domains were described as follows:

More recently, Dave Snowden has been describing them as “Obvious”, “Complicated”, “Complex”, and “Chaotic.”

Obvious

In the ‘obvious’ domain we truly do have known causes and effects where relationships are linear and generally not open to dispute. Here we can define standard operating procedures, use process reengineering, and generally define and incrementally improve best practice / ‘the right way.’ The decision model is to sense incoming data, categorize that data, and then respond in accordance with pre-determined practice.

Complicated

When things start to get complicated we have knowable causes and effects, but they may not be fully known to us. One thing that leads to this situation is causes and effects separated over time and space in chains that are difficult to fully understand. In the complicated domain, we often rely on expert opinion.

This is the domain of systems thinking, the learning organization, and the adaptive enterprise, all of which are too often confused with complexity theory… This is the domain of methodology, which seeks to identify cause-effect relationships through the study of properties which appear to be associated with qualities.

The decision model in the complicated domain is to sense incoming data, analyze that data, and then respond in accordance with expert advice or analysis interpretation. Entrained patterns are dangerous here, as a simple error in an assumption can lead to a false conclusion that is hard to isolate and difficult to spot.

Complex

When we move from the merely complicated to the complex, we’re entering the world of un-order. This is the domain of complexity theory. Emergent patterns can be perceived, but not predicted, a phenomenon called retrospective coherence. And this combination of perception without the ability to predict can get us into all sorts of troubles if we confuse the two:

In this space, structured methods that seize upon such retrospectively coherent patterns and codify them into procedures will confront only new and different patterns for which they are ill prepared. Once a pattern has stabilized, its path appears logical, but in only one of many that could have stabilized, each of which would also have appeared logical in retrospect.

If we rely on expert opinions, case studies, business books claiming to have found ‘the answer’ and so on in this domain then we will continue to be surprised by new and unexpected patterns. In the complex domain then, the decision model is to create probes to make the patterns or potential patterns more visible before we take any action. If we sense desirable patterns we can respond by stabilising them. Likewise we can destabilise any patterns we don’t want. To encourage the establishment of healthy patterns, we can seed the space in such a way that patterns we want are more likely to emerge (in the YouTube talk I reference earlier, Dave refers to these as attractors).

Understanding this space requires us to gain multiple perspectives on the nature of the system. This is the time to “stand still” (but pay attention) and gain new perspective on the situation… The methods, tools, and techniques of the known (obvious) and knowable (complicated) domains do not work here. Narrative techniques are particularly powerful in this space.

Chaotic

In the chaotic domain there are no perceivable cause and effect relations and the system is turbulent. In this domain there is nothing to analyse, and no patterns to emerge. The decision model here is to act, quickly, and decisively, to reduce the turbulence. Then we can sense the reaction and respond accordingly.

The trajectory of our intervention will differ according to the nature of the space. We may use an authoritarian intervention to control the space and make it knowable or known; or we may need to focus on multiple interventions to create new patterns and thereby move the situation into the complex space.

Disorder

The central domain of disorder is where we do not understand which of the other domains we are in.

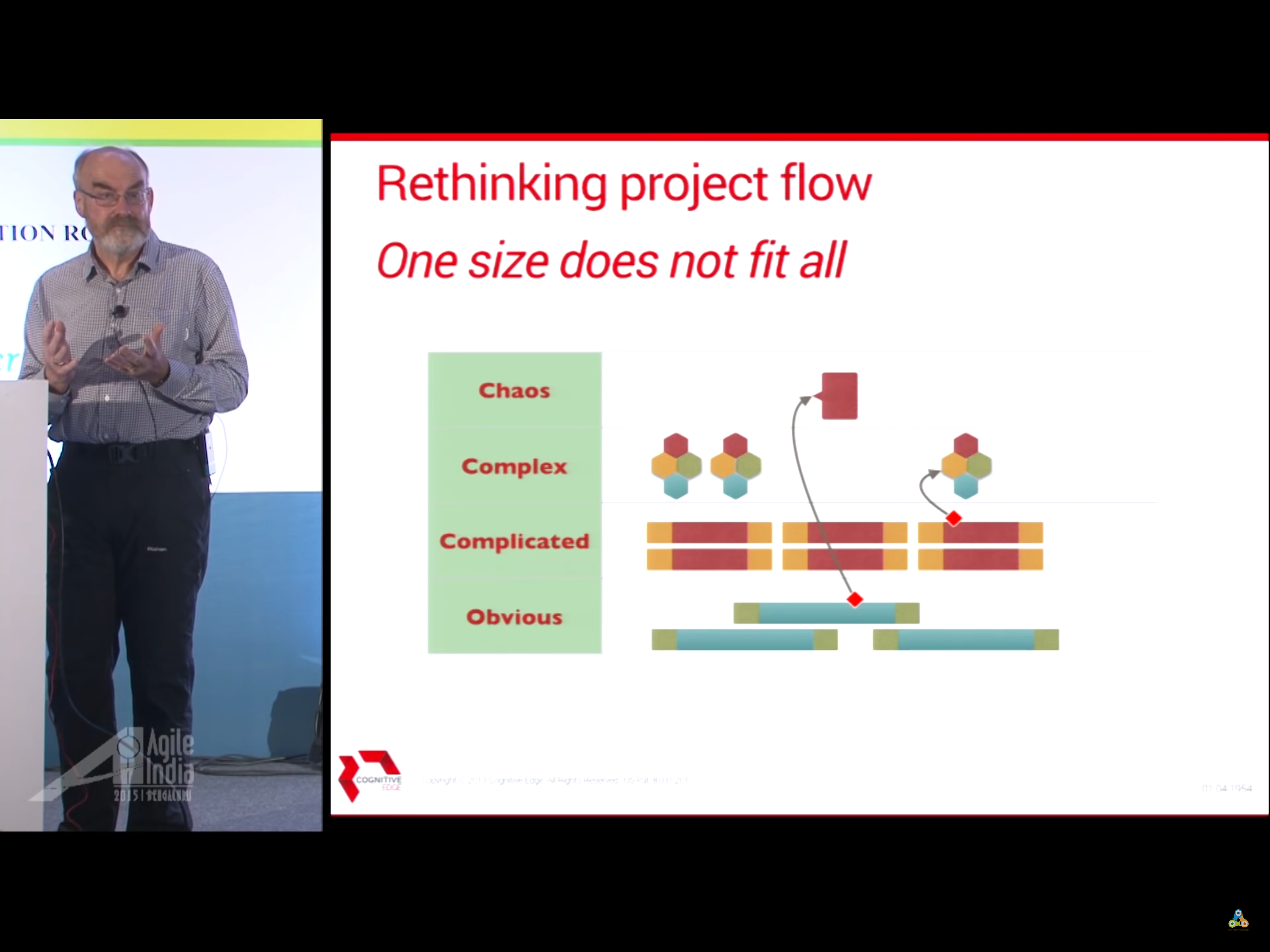

Cynefin and software development

Drawing some material from Dave Snowden’s Agile India keynote, we can see how the approach to building software changes in each of these domains. (I’m reminded of some of Simon Wardley’s writings on one-size development methodologies not fitting all).

In an obvious domain, we could use strong process and even a waterfall. In a complicated domain though, we want to use a more iterative process giving us opportunities to analyse and respond. Complex domains suit rapid construction of many prototypes (maybe even in parallel) to see what works. When in chaos, spike!

Moving between domains

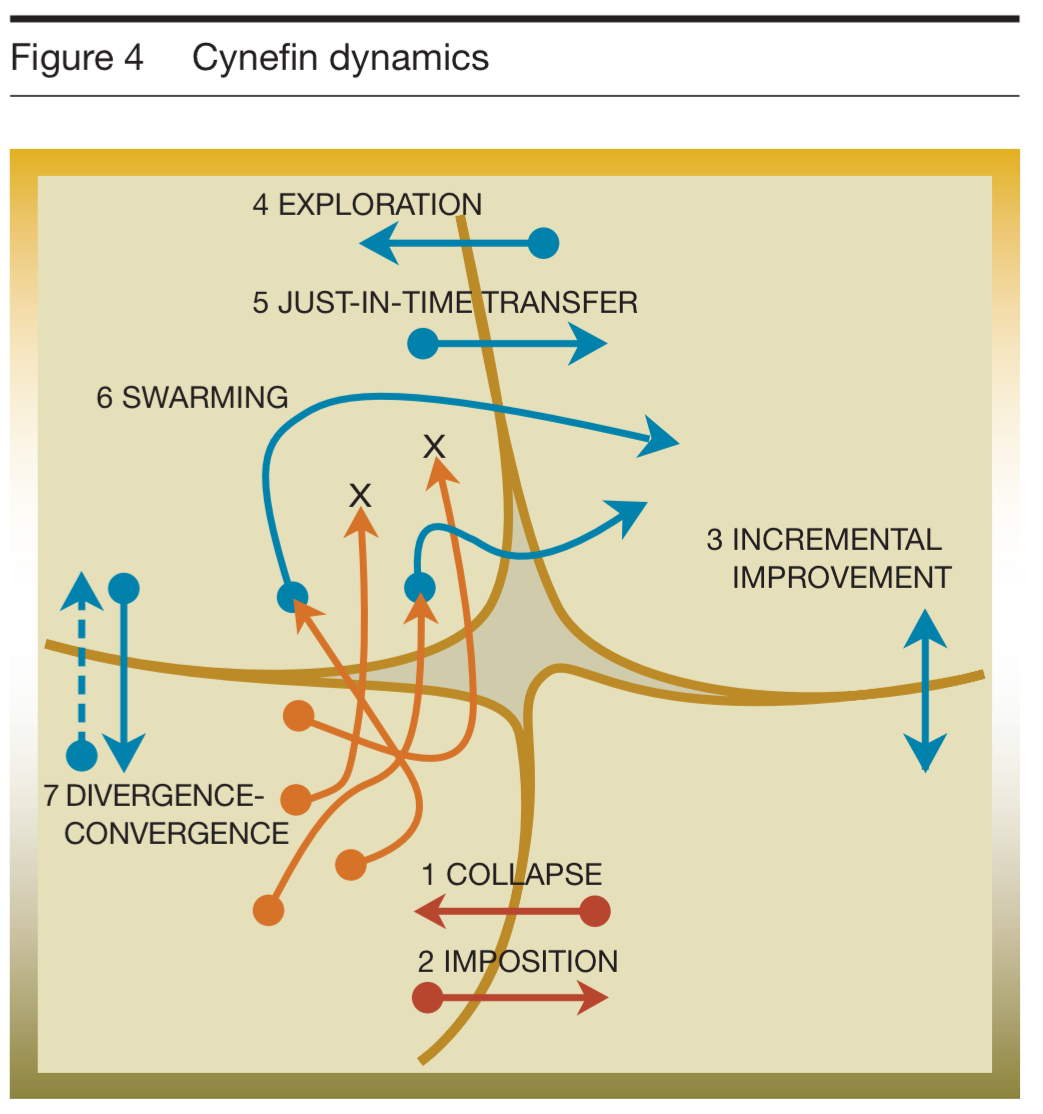

A lot of the writing on Cynefin focuses on ‘categorizing’ systems into one of the domains just described. But in the paper, the authors place a lot of emphasis on the transitions that occur between domains.

When people use the Cynefin framework, the way they think about moving between domains is as important as the way they think about the domain they are in, because a move across boundaries requires a shift to a different model of understanding and interpretation as well as a different leadership style.

The paper describes a series of cross-boundary movements and flows, for example:

See the full paper for further details.

There are also background movements at work. The forces of the past tend to cause a clockwise drift in the Cynefin space (ossification). The forces of the future push things in a counter-clockwise direction:

…the death of people and obsolescence of roles cause what is known to be forgotten and require seeking; new generations filled with curiosity begin new explorations that question the validity of established patterns; the energy of youth breaks the rules and brings radical shifts in power and perspective; and sometimes imposition of order is the result.

The two forces pull society in both directions at once: “the old guard is forgotten at the same time that its beliefs affect newcomers in ways they cannot see.”

Typo: “It Neither ordered in the traditional senses, nor disordered, but somewhere in-between.” should (probably) be “It is neither ordered in the traditional sense, nor disordered, but somewhere in-between.”

Perhaps startups (and new products) progress through markets that develop in the same fashion. If Chaotic, Complex, Complicated, Obvious often map to Seed, Series A, B, C that would indicate what types of leadership and development methods are most useful in each phase.

Reblogged this on aainslie.