How Much Up-Front? A Grounded Theory of Agile Architecture – Waterman et al. 2015

It’s time for something a little bit different, so this week I thought I’d bring you a selection of papers from the recently held ICSE’15 conference (International Conference on Software Engineering). To kick things off, today’s choice looks at the question of how architecture fits into an agile process. Just how much effort should you spend up-front on architecture? And what happens if you defer architectural decisions to later? It’s all a bit of a conundrum…

Software architecture is the high-level structure and organisation of a software system. Because architecture defines system-level properties, it is difficult to change after development has started, causing a conflict with agile development’s central goal of better delivering value through responding to change. To maximise agility, agile developers often avoid or minimise architectural planning, because architecture planning is often seen as delivering little immediate value to the customer. Too little planning however may lead to an accidental architecture that has not been carefully thought through, and may lead to the team spending a lot of time fixing architecture problems and not enough time delivering functionality (value).

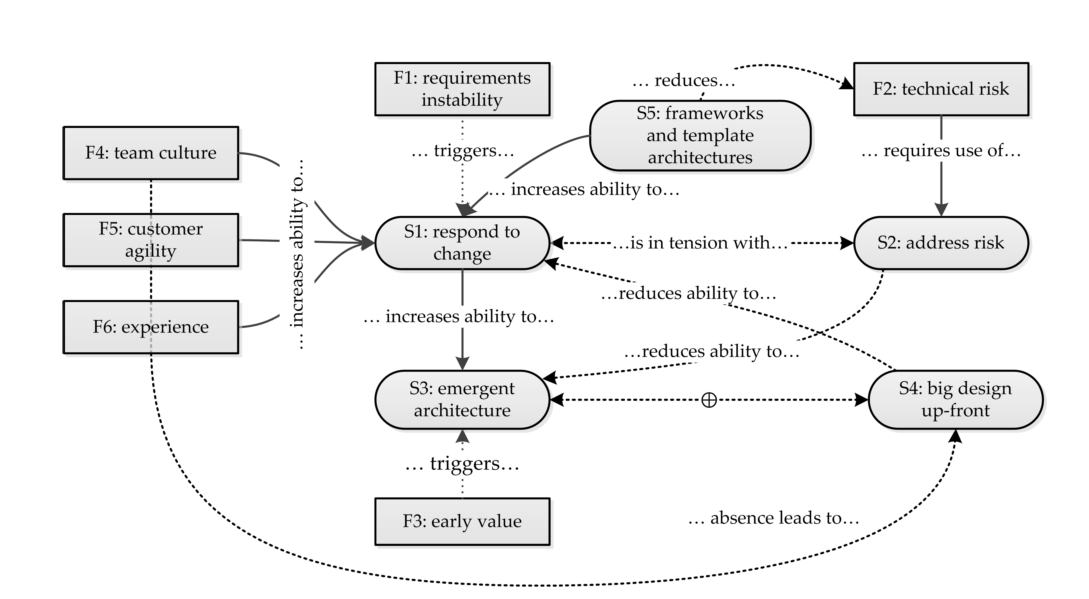

A common strategy is to do ‘just enough’ architecture up-front. But how much is just enough? This paper identifies six forces that shape the answer to that question, leading to five different agile architecture strategies that can be used. The grounded theory reference in the paper title is a reference to the approach used to derive these forces and strategies. I found it interesting to read the explanation of grounded theory in the paper, and encourage you to take look if this piques your interest (section II C). The short version is that it’s an iterative bottom-up approach based on coding and clustering information given during structured interviews. The end result is a theory explaining how things relate to each other. This is in contrast to starting with a hypothesis and designing a test to prove or disprove it.

We interviewed 44 participants in 37 interviews. Participants were gathered through industry contacts, agile interest groups and through direct contact with relevant organisations. Almost all participants were very experienced architects, senior developers, team leaders and development managers with at least six years’ experience (twenty years was not uncommon), and most were also very experienced in agile development.

The six forces and five strategies that emerged from the work are summarised in the figure below.

Six Forces that Influence the Approach to Agile Architecture

- Requirements Instability due to incomplete or changing requirements favours deferring detailed requirements gathering, analysis, and architecture design in return for getting early feedback from the customer based on an initial implementation.

- Technical Risk through challenging or demanding architecturally significant requirements, through having many integration points with other systems, and by involving legacy systems, is a force in favour of more up-front architecture.

Participants also identified integration points, or interfaces to external systems, as a major source of complexity in the systems being developed, particularly when the other systems are legacy or are built from different technologies. Integration with other systems require data and communications to be mapped between the systems, adding to the up-front effort to ensure integration is possible with the technologies being used. For example: “Today’s systems tend to be more interconnected – they have a lot more interfaces to external systems than older systems which are typically standalone. They have a lot higher level of complexity for the same sized system.” (P14, solutions architect)

Interestingly a similar argument can be made about the complexity introduced by microservices.

- Early Value : there is a need to start getting early value out of a system or product being built (not just feedback) before all functionality has been implemented. For example, to take advantage of a market opportunity or to use the revenue generated to fund further development. This force works against too much up-front architecture:

Teams that deliver early value must reduce the time to the first release by spending less time on up-front architecture design. They achieve this by reducing the planning horizon – how far ahead the team considers (high level) requirements for the purpose of architecture planning.

- Team Culture that is people-focused and collaborative is very important in fostering collaboration. “A team without a trusting people-focused and collaborative culture has to rely on documentation for communication and formal plans, and hence requires more up-front effort to guide development.”

-

Customer Agility is often required to match an agile approach to architecture.

A customer must have an agile culture that is similar to the team’s culture, whether the team is in-house or an ISV (independent software vendor), for the team to be truly agile. A highly-agile team will not fit in well with a heavyweight process-oriented organisation that prefers planning and formal communication.

- Experience enables pattern recognition that can short-circuit the amount of work needed to be done up-front.

While generally important for all software development methods, experience is more important in agile development because the tacit knowledge and implicit decision-making that come with experience supports agile development’s reduced process and documentation, and reduces the up-front effort: “You implement certain patterns without thinking […] you’ve done this kind of pattern for solving this kind of a problem, without even thinking that this is the way that you are going.” (P16b, head of engineering)

Five Strategies for Implementing Agile Architecture

In response to these forces there are five strategies that a team may choose from…

- Respond to change

A team’s ability to use S1 (RESPOND TO CHANGE) is directly related to how agile it is. S1 increases the architecture’s agility by increasing its modifiability and its tolerance of change, and allows the team to ensure the architecture continuously represents the best solution to the problem as it evolves.

We are given five tactics for responding to change: keep designs simple, prove the architecture with code iteratively, use good design practices, delay-decision making, and plan for options. The first and last of these are in tension, which becomes more obvious when we juxtapose the descriptions in the paper:

Keeping designs simple means only designing for what is immediately required: no gold plating and no designing for what might be required or for what can be deferred… Planning for options means building in generality and avoiding making decisions that are unnecessarily constrained and which may close off possible future requirements without significant refactoring.

- Address Risk

S2 (ADDRESS RISK) reduces the impact of risk before it causes problems, and is usually done up-front, particularly for risk relating to system-wide decisions (for example, risk in selecting the technology stack or top-level styles). Using S2, a team designs the architecture in sufficient detail that it is comfortable that it is actually possible to build the system with the required Architecturally Significant Requirements with a satisfactory level of risk.

- Emergent Architecture is likely to be used when developing a minimum viable product in response to the Early Value force. The team makes only the minimal architectural decisions up-front such as selecting the technology stack and the highest level architectural styles and patterns.

-

Big Design Up-Front

S4 (BIG DESIGN UP-FRONT) requires that the team acquires a full set of requirements and completes a full architecture design before development starts. There are no emergent design decisions, although the architecture may evolve during development. S4 is undesirable in agile development because it reduces the architecture’s ability to use S1 (RESPOND TO CHANGE) by increasing the time to the first opportunity for feedback, increasing the chance that decisions will need to be changed later, and increasing the chance of over-engineering. While S4 may be considered the case of addressing risk (S2) taken to the extreme, in reality the use of S4 is driven primarily by an absence of CUSTOMER AGILITY (F5) rather than the presence of TECHNICAL RISK (F2).

- Using Frameworks and Template Architectures using software frameworks and the reference architectures from their creators provides the benefit of standard solutions to standard problems.