Towards multiverse databases Marzoev et al., HotOS’19

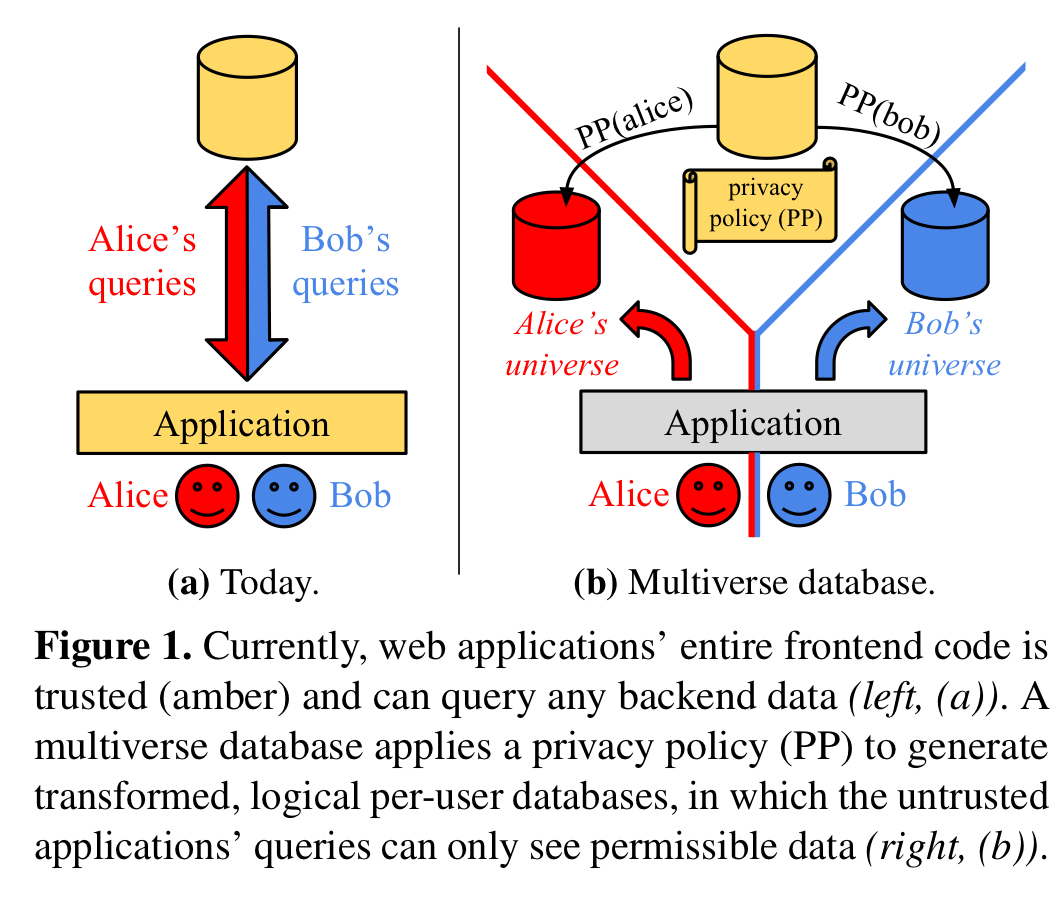

A typical backing store for a web application contains data for many users. The application makes queries on behalf of an authenticated user, but it is up to the application itself to make sure that the user only sees data they are entitled to see.

Any frontend can access the whole store, regardless of the application user consuming the results. Therefore, frontend code is responsible for permission checks and privacy-preserving transformations that protect user’s data. This is dangerous and error-prone, and has caused many real-world bugs… the trusted computing base (TCB) effectively includes the entire application.

The central idea behind multiverse databases is to push the data access and privacy rules into the database itself. The database takes on responsibility for authorization and transformation, and the application retains responsibility only for authentication and correct delegation of the authenticated principal on a database call. Such a design rules out an entire class of application errors, protecting private data from accidentally leaking.

It would be safer and easier to specify and transparently enforce access policies once, at the shared backend store interface. Although state-of-the-are databases have security features designed for exactly this purpose, such as row-level access policies and grants of views, these features are too limiting for many web applications.

In particular, data-dependent privacy policies may not fit neatly into row- or column-level access controls, and it may be permissible to expose aggregate or transformed information that traditional access control would prevent.

With multiverse databases, each user sees a consistent “parallel universe” database containing only the data that user is allowed to see. Thus an application can issue any query, and we can rest safe in the knowledge that it will only see permitted data.

The challenging thing of course, is efficiently maintaining all of these parallel universes. We’ll get to that, but first let’s look at some examples of privacy policies and how they can be expressed.

Expressing privacy policies

In the prototype implementation, policies are expressed in a language similar to Google Cloud Firestore security rules. A policy just needs to be a deterministic function of a given update’s record data and the database contents. Today the following are supported:

- Row suppression policies (e.g. exclude rows matching this pattern)

- Column rewrite policies (e.g. translate / mask values)

- Group policies, supporting role-based (i.e., data-dependent access controls)

- Aggregation policies, which restrict a universe to see certain tables or columns only in aggregated or differentially private form.

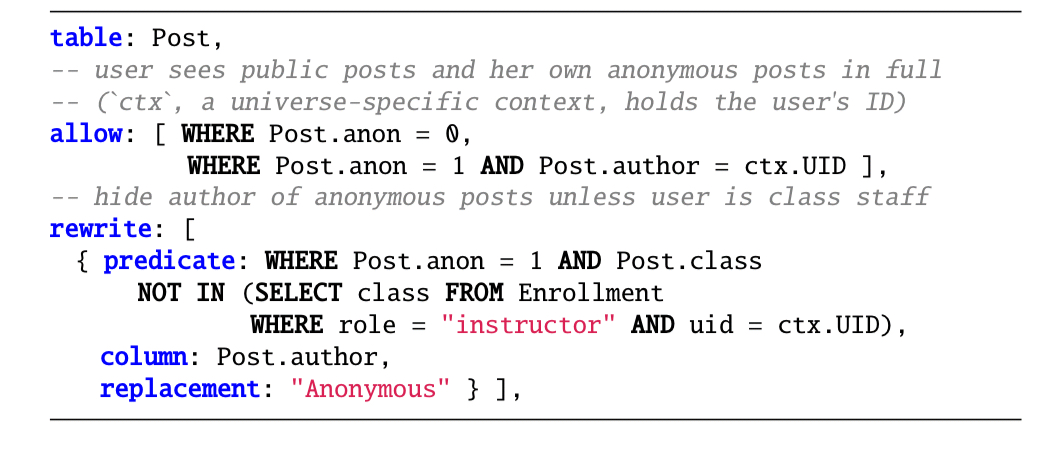

Consider a class discussion forum application (e.g. Piazza) in which students can post questions that are anonymous to other students, but not anonymous to instructors. We can express this policy with a combination of row suppression and column rewriting:

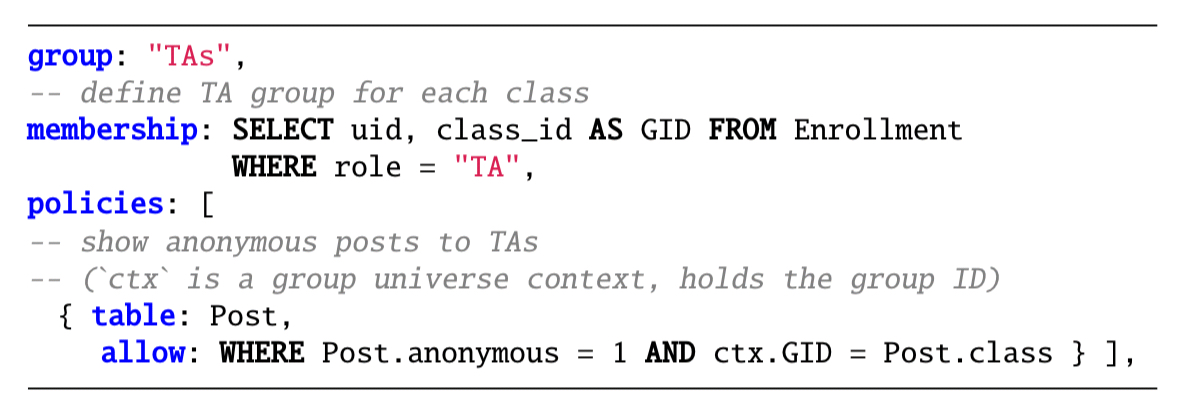

Maybe we want to allow teaching assistants (TAs) to see anonymous posts in the classes they teach. We can define a group via a membership condition and then attach policies to that group:

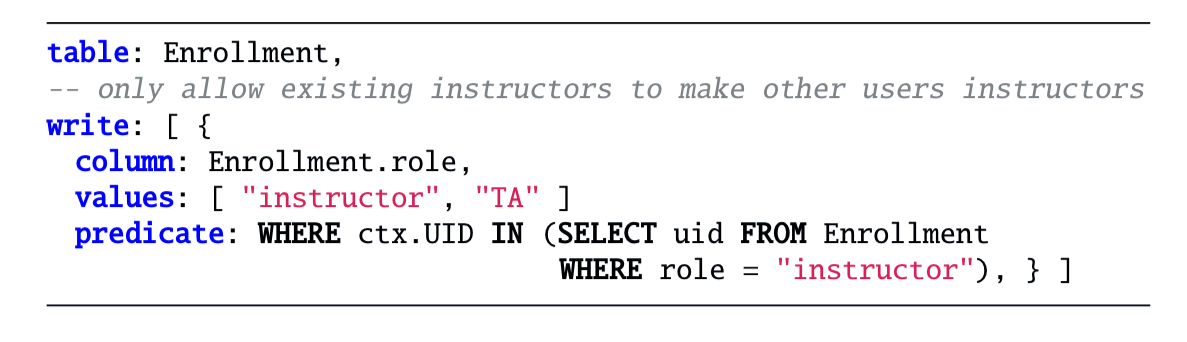

Write policies (not supported in the current implementation) permit specification of allowed updates. For example:

An aggregation policy could be used to rewrite any matching aggregation into a differentially-private version. The basis for this could be e.g. Chan et al.’s ‘Private and continual release of statistics’. Composing such policies with other policies remains an open research question.

Managing universes

A multiverse database consists of a base universe, which represents the database without any read-side privacy policies applied, and many user universes, which are transformed copies of the database.

For good query performance we’d like to pre-compute these per-user universes. If we do that naively though, we’re going to end up with a lot of universes to store and maintain and the storage requirements alone will be prohibitive.

A space- and compute-efficient multiverse database clearly cannot materialize all user universes in their entirety, and must support high-performance incremental updates to the user universes. It therefore requires partially-materialized views that support high-performance updates. Recent research has provided this missing key primitive. Specifically, scalable, parallel streaming dataflow computing systems now support partially-stateful and dynamically-changing dataflows. These ideas make an efficient multiverse database possible.

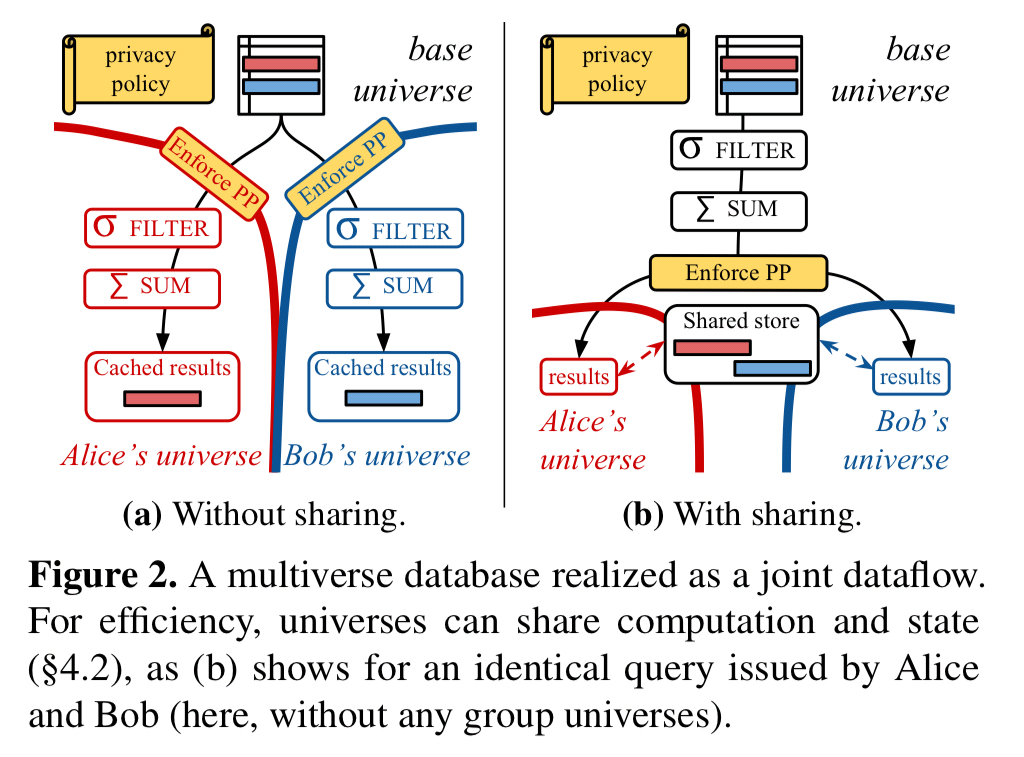

So, we make the database tables in the base universe be the root vertices of a dataflow, and as the base universe is updated records move through the flow into user universes. Where an edge in the dataflow graph crosses a universe boundary, any necessary dataflow operators to enforce the required privacy policies are inserted. All applicable policies are applied on every edge that transitions into a given user universe, so whichever path data takes to get there we know the policies will have been enforced.

We can build the dataflow graph up dynamically, extending the flow’s for a user’s universe the first time a query is executed. The amount of computation required on a base update can be reduced by sharing computation and cached data between universes. Implementing this as a joint partially-stateful dataflow is the key to doing this safely.

By reasoning about all users’ queries as a joint dataflow, the system can detect such sharing: when identical dataflow paths exist, they can be merged.

Logically distinct, but functionally equivalent dataflow vertices can also share a common backing store. Any record reaching such a vertex in a given universe implies that universe has access to it, so the system can safely expose the shared copy.

Just as user universes can be created on demand, so inactive universes can be destroyed on demand as well. Under the covers, these are all manipulations of the dataflow graph, which partially-stateful dataflow can support without downtime.

Prototype evaluation

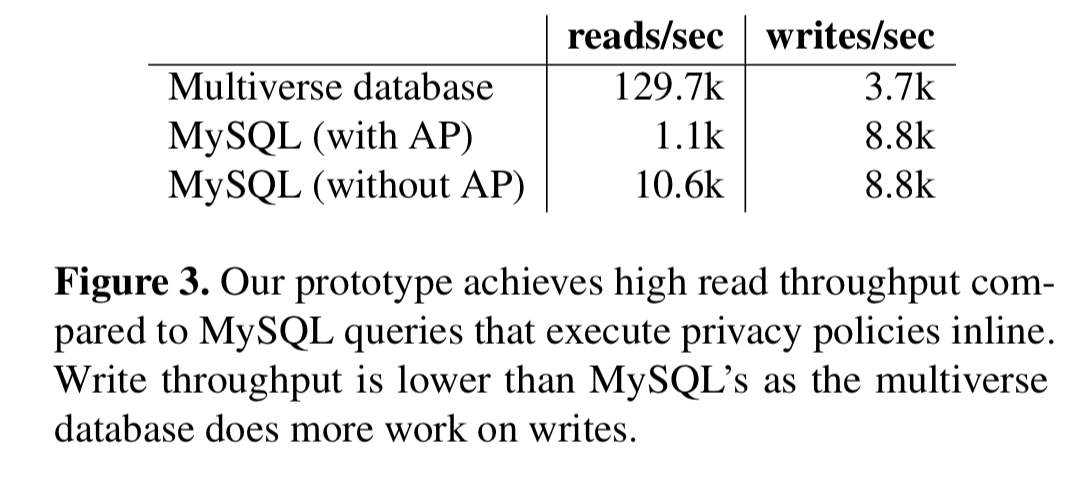

The authors have built a prototype implementation of these ideas based on the Noria dataflow engine. It runs to about 2,000 lines of Rust. A Piazza-style class forum discussion application with 1M posts, 1,000 classes, and a privacy policy allowing TAs to see anonymous posts is used as the basis for benchmarking.

The team compare the prototype with 5,000 active user universes, a MySQL implementation with inlined privacy policies (‘with AP’) and a MySQL implementation that does not enforce the privacy policy (‘without AP’):

Since the prototype is serving reads from a pre-computed universe stored in memory cached results are fast and make for a very favourable comparison against MySQL. Writes are significantly slower though (about 2x) – much of this overhead is in the implementation rather than essential. Memory footprint is 0.5GB with one universe, and 1.1GB with 5,000 universes, introduces a shared record store for identical queries reduces their space footprint by 94%.

These results are encouraging, but a realistic multiverse database must further reduce memory overhead and efficiently run millions of user universes across machines. Neither Noria nor any other current dataflow system support execution of the huge dataflows that such a deployment requires. In particular, changes to the dataflow must avoid full traversals of the dataflow graph for faster universe creation.

Support for write authorization policies (with some tricky consistency considerations for data-dependent policies) is future work, as is the development of a policy-checker (perhaps similar to Amazon’s SMT-based policy checker for AWS) to help ensure policies themselves are consistent and complete.

Our initial results indicate that a large, dynamic, and partially-stateful dataflow can support practical multiverse databases that are easy to use and achieve good performance and acceptable overheads. We are excited to further explore the multiverse database paradigm and associated research directions.