Learning networking by reproducing research results Yan & McKeown et al., SIGCOMM’17

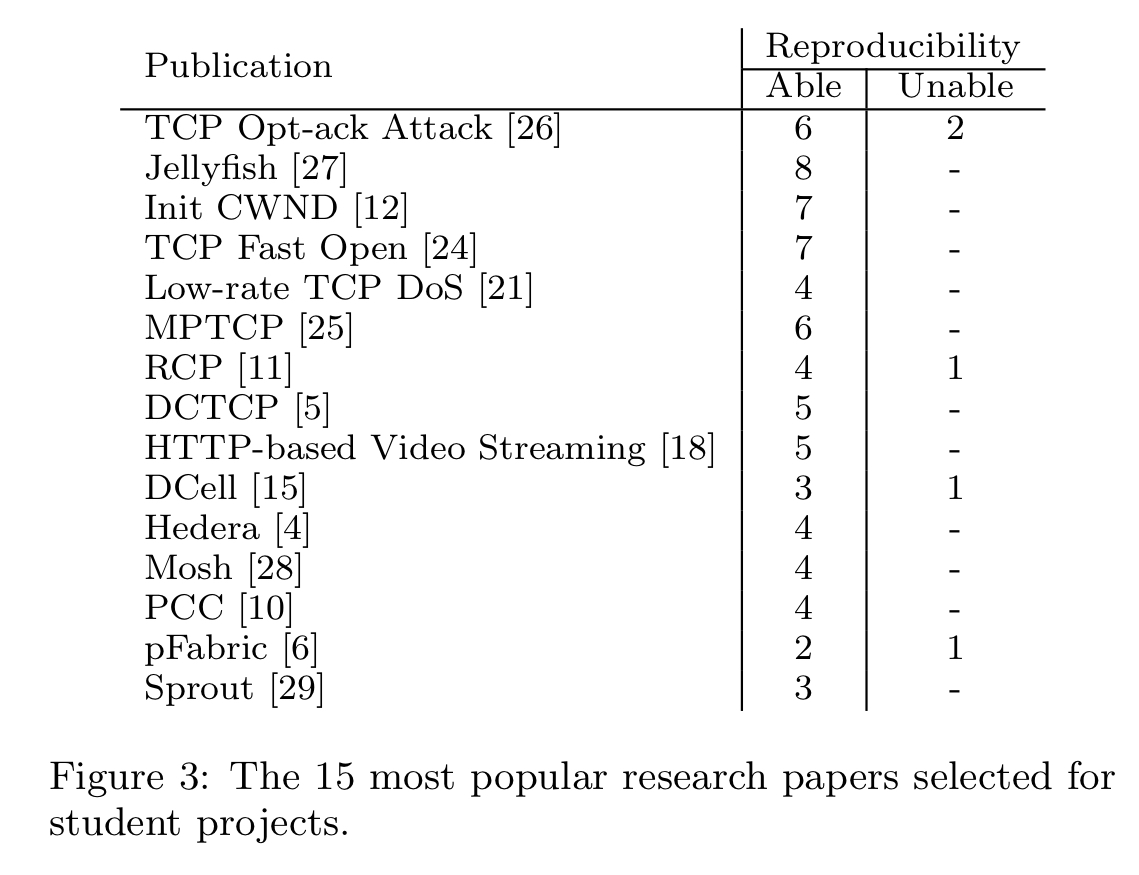

Students taking Stanford’s Advanced Topics in Networking class have to select a networking research paper and reproduce a result from it as part of a three-week pair project. At the end of the process, they publish their findings on the course’s public Reproducing Network Research blog. It’s well worth having a look around the blog: the students manage to achieve a lot in only three weeks! In the last five years, 200 students have reproduced results from 40 papers.

In ‘Learning networking by reproducing research results’ the authors explain how this reproduction project came to be part of the course, what happens when students try to reproduce research, and the many benefits the students get from the experience. It’s a wonderful and inspiring idea that I’m sure could be applied more broadly too.

We began the project as a means of teaching both engineering rigor and critical thinking, qualities that are necessary for careers in networking research and industry. We have observed that reproducing research can simultaneously be a tool for education and a means for students to contribute to the networking community.

Why a reproducibility project?

In high-school science students repeat well-known experiments in the lab, and it is widely agreed that this gives them a much deeper understanding of the underlying concepts.

Our main goal for adapting this scientific approach to our networking class is for students to obtain a detailed, in-depth understanding of a significant paper, its key ideas, and its key results.

Over and above just getting to the results, the act of recreation itself proves to be valuable and rewarding – perhaps more so even than whether or not identical results are actually achieved in the end.

In fact, we find that students learn a huge amount when their experiments yield different results from the original research: they must figure out where the discrepancies lie and discern if there are unstated assumptions or inaccuracies in their own results or the published results. This is a fascinating and educational experience, and often a good lesson in diplomacy.

Studying a paper in order to reproduce it leads to much deeper reflection on, and understanding of the paper. You could think of it as the logical fourth pass of Keshav’s three-pass approach in ‘How to Read a Paper.’ It also helps to instil in future researchers the principle that their results should be reproducible by others whenever possible. Publishing their own reproducible results on the course blog encourages the whole community to do likewise.

How the projects are run

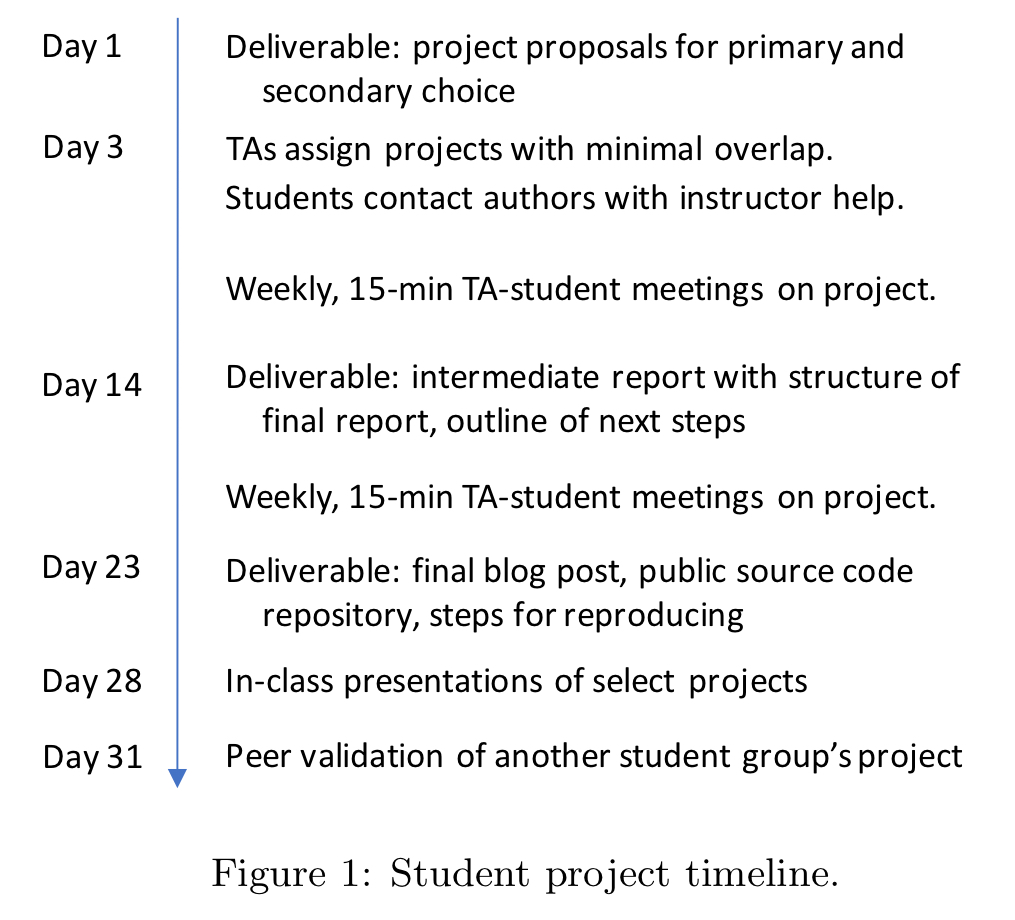

Students work in pairs and have three weeks out of a ten-week course to complete the assignment.

ONE: The first step is to choose a central figure or table from a research paper of interest.

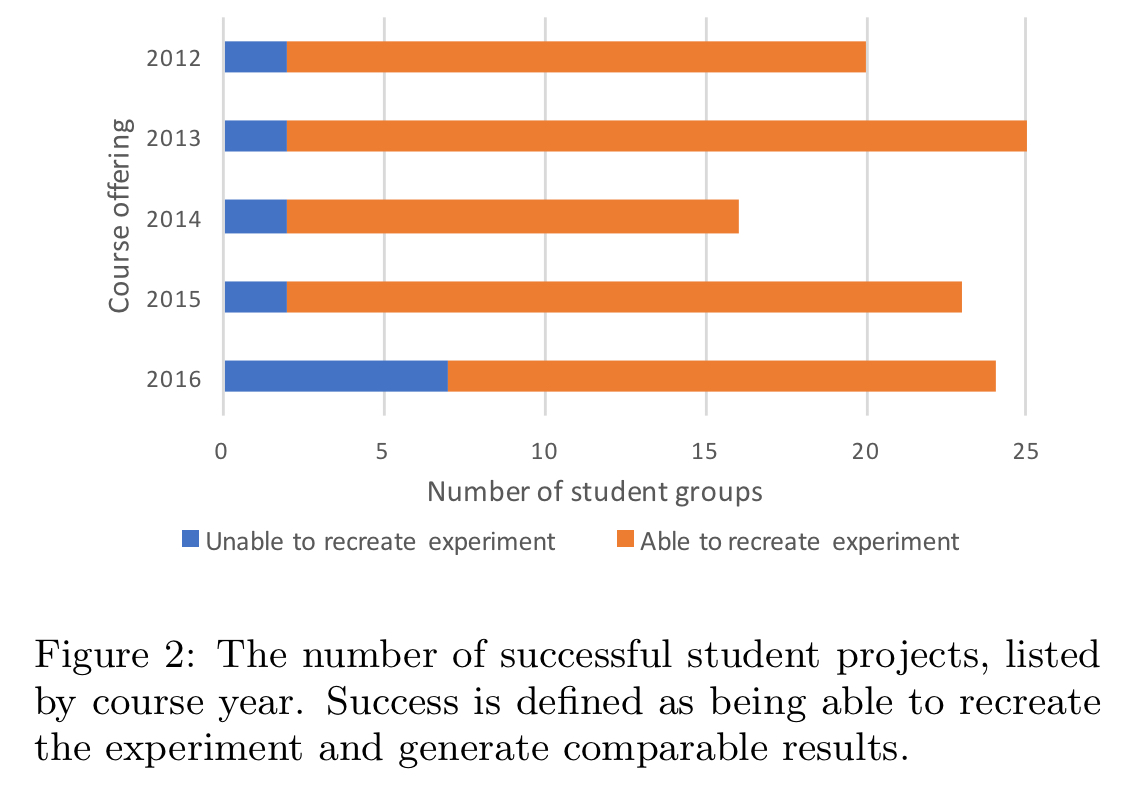

To get the students started, we provide a list of suggested conferences and research publications that we think make good examples, and we encourage students to choose more recent works, or ones that have not yet been attempted by students in previous course offerings. At Stanford, we have had students successfully reproduce results ranging from widely cited papers such as Hedera and DCTCP to traditional papers like RED, to cutting-edge, as-yet unpublished work like SPDY.

Here are the most popular chosen papers:

TWO: The students then need to figure out their strategy for trying to reproduce the results, with use of either the Mininet or Mahimahi emulators encouraged.

THREE: The next step, which I’m sure is where part of the magic happens, is that the students are helped to contact the paper authors.

Opening up this communication channel between students and researchers has two main benefits: the first is for the student, who now has a primary source to contact regarding the tools, setup, workload and use-cases of the given experiment or research tool. The second is for the researcher, who is now aware that his or her work is being analyzed critically… the researcher will have additional feedback on the benefits, caveats, and persistence of his or her findings.

FOUR: Then of course the students work with the instructors, peers, and teaching assistants to recreate the research.

FIVE: A public blog is posted, which must contain all the code and workload in order for someone else to easily repeat experiments too. (And many do come to the blog for that purpose).

SIX: The results in every blog post are verified using peer validation – every student group is required to replicate the results of another student group. “This reproduction effort is required to be an easy two-step process: (1) download and install any code, and (2) click ‘run.’ All code must be available in public code repositories.”

Most projects are successful, although a few are not.

Sometimes students can recreate the original work almost perfectly (subject to scaling or computational resource limits). Other times students find discrepancies between their own results and those in the paper, and investigate why. For example, one group found that the settings used for ECMP had a material impact on results, but the configuration used in the original testbed was not available. Sometimes other changes in the environment (such as TCP implementations moving on since the original date of publication of the paper) hamper recreation, and other times of course the students end up being a little bit too ambitious in their undertakings! The teaching staff try to coach the students to help them avoid this latter mistake.

Benefits for participants and the research community

My favourite piece of the whole process is the way that it tears down a mental barrier that might otherwise hold back students from full engagement in the research community:

An unexpected outcome of this project is an increased role of students in the networking research community. While designing and running the experiments, students had to interact with the original authors, new researchers who came across our course blog, and even developers of the emulators or simulators. We believe the benefits of these interactions go both ways; the networking community at large can also benefit from these student research reproduction projects.

Students themselves found multiple benefits from the course:

- “I specifically like the level of familiarity I got with the paper. There’s a level you can only get by reproducing or implementing it.”

- It introduced them to cutting-edge research. For example, one pair were inspired to reproduce QJump.

- It gave them confidence to use research results in their own work. For example, one of the students working on the QJump project went on to implement a similar scheduler in her own research, “which is something that I wouldn’t have done if [I had just read] the paper.”

- It made them realise that papers could be understood, “even by students who have taken only two courses in networking, and results can be reproduced in part.”

- They felt good about publishing the blog posts as a contribution in their own right. “[From an educational standpoint,] blog posts are easier to read than papers. If there is one cool idea from a paper that you can reproduce and put into a blog post, I think that could be very valuable.”

- The practical skills gained from the reproduction experiments proved useful when students went on to work in industry.

The last word

We have found that the experience is rewarding and interesting for the students, and it gives them a chance to interact with researchers. In addition, we have learned that documenting the results of these reproduction studies is an essential resource for both future students and the research community at large. We hope that the materials presented in this editorial inspire you to consider offering similar projects in your graduate networking courses too.

I wonder where else this approach might be applied. For example, in distributed systems students might try to model an algorithm using TLA+ (as Murat Demirbas teaches them to do in his course: see ‘My experience with using TLA+ in distributed systems classes’), and in programming languages papers critical proofs could be reconstructed in Coq.

On a similar note, the Student Cluster Competition at SC’17 makes use of a reproducibility challenge, where teams are expected to reproduce the results of a selected paper [0]. This year it’s the Vectorization of the Tersoff Multi-body Potential [1]. Overall, teams are expected to read the paper, figure out what the claims are, try to reproduce the results on a cluster your team built, and then analyze the final results.

As a student participating in this challenge, I can say that the challenge has been a really fun and illuminating experience. It’s given me the chance to deep dive into some computer architecture (vectorization, intrinsics, etc), and also get some basic exposure in molecular body simulations.

> An unexpected outcome of this project is an increased role of students in the networking research community.

This is in line with my experiences, as well. One challenge we faced was that the specific paper experimented exclusively on Intel clusters, whereas we were running a Power machine. Since they hosted their optimizations on Github, we were able to create issues when we had challenges porting to our machine (which we quickly resolved).

All in, a really fun experience. I think this “reproducing canonical papers” would be a fun and hands on way to learn about a new field.

That said, I do question the feasibility of this as a pedagogical approach. We were able to “luck” out because (1) the paper’s author, Markus, had to compete to have his paper published, and (2) he was very helpful, (porting the code to Power, answering followup questions, etc.) In a sense, this was “easy” mode. However, there are a number of cases where it’s simply building a paper’s code is nontrivial. For example, a few researchers at Arizona tried to simply obtain and build the code of 613 papers from ASPLOS’12, CCS’12, OOPSLA’12, OSDI’12, PLDI’12, SIGMOD’12, SOSP’11, VLDB’12, TACO’9, TISSEC’15, TOCS’30, TODS’37, TOPLAS’34 [2]. Of these 613 papers, they had a ~25% success rate, where success means they were able to build and get a basic run.

[0]http://www.studentclustercompetition.us/2017/applications.html

[1]https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3014914

[2]http://reproducibility.cs.arizona.edu/tr.pdf

This sounds like a great idea. I am tempted to try it in a course of my own in the spring.

Might I also suggest considering to encourage your students to submit their replications to ReScience: http://rescience.github.io/? This is a web-only (in fact, GitHub-based) journal that publishes replications of computational science results (disclaimer: I am associate editor of this journal).