Data on the Outside vs Data on the Inside Pat Helland, CIDR 2005

Another (modern) classic today, Pat Helland’s wonderful 2005 paper on thinking about data in service oriented architectures. Sticking with the contemporary feel I’m going to write SOA as ‘microservices’ for the rest of this post. Helland shows us that we need to think very differently about the data encapsulated inside of a service, and the data that is exchanged between services. The move from a monolith to microservices does something much deeper than just refactor the code into convenient independently deployable modules:

Going to microservices is like going from Newton’s physics to Einstein’s physics. Newton’s time marched forward uniformly with instant knowledge at a distance. Before microservices, distributed computing strove to make many systems look like one with RPC, 2PC etc.. In Einstein’s universe, everything is relative to one’s perspective. Microservices has “now” inside (a service) and the “past” arriving in messages.

Perhaps we should rename the “extract microservice” refactoring operation to “change model of time and space” ;).

Recently, a lot of interest has been shown in microservices. In these systems, there are multiple services each with its own code and data, and ability to operate independently of its partners… This paper proposes there are a number of seminal differences between data inside a service and data sent into the space outside of the service boundary.

Let’s dive in…

Services encapsulate the data that they own. Any changes to this data, and all reads of the data, go through a well-defined service interface. Only the trusted application logic of the service can perform changes. There are no ACID transactions across service boundaries:

To participate in an ACID transaction requires a willingness to hold database locks until the transaction coordinator decides to commit or abort the transaction. For the non-coordinator, this a serious ceding of independence…

“Data on the inside” refers to the encapsulated private data contained within a service, and “data on the outside” refers to the information that flows between independent services.

Past, Present, Future, and “then”

Inside a service we can use transactional access to data, with transaction isolation giving the illusion that each transaction executes at a well-defined moment in time…

ACID transactions live in the “now”. As time marches forward and transactions commit, each new transaction perceives the input of the transactions that preceded it. The executing logic of the service lives with a clear and crisp sense of “now”.

Messages sent by a service may frequently contain service data – no locks on this data will be held by the sending service as the outgoing message is sent. Therefore, by the time a recipient processes the message, the original data in the sending service may have changed.

The contents of a message are always from the past! They are never “now.”

Every service has its own perspective with inside data providing a view of now, its outside data providing a view of the past. Command messages requesting that some other service do work are “hopeful for the future.”

Thus we have an inter-mingling of past, present, and future:

Operands may live either in the past or the future depending on their usage pattern. They live in the past if they have copies of unlocked information from a distant service. They live in the future if they contain proposed values that hopefully will be used if the operator is successfully completed. Between the services, life is in the world of “then”… This means that data on the outside lives in the world of “then”. It is past or future but it is not now.

With each service living in its own now, it is up to the service logic to reconcile that now with incoming and outgoing notions of “then”.

Implications for outside data

Data on the outside must be immutable and identifiable so that it is the same no matter when or where it is referenced. Within a service, you can refer to “The New York Times” and always mean the current version. “The New York Times” here serves as a version independent identifier. But when data goes on the outside just saying “The New York Times” is no longer enough, the version independent identifier needs to be converted to a version dependent identifier. For example, “The New York Times on Jan 4th 2005, California Edition.”

Immutability isn’t enough to ensure a lack of confusion. The interpretation of the contents of the data must be unambiguous. Stable data has an unambiguous and unchanging interpretation across space and time… One excellent technique for the creation of stable data is the use of time-stamping and/or versioning. Another important technique is to ensure that important identifiers are never reused.

Messages themselves must also be immutable (e.g. their content should never change across retries). Not only that, but the schema for the message must be immutable.

For this reason, it is recommended that all message schemas be versioned and each message use the version dependent identifier of the precise definition of the message format.

(Later on in the paper, Helland discusses schema that allow for extensibility).

When referencing other data, it is also essential that the identifier used for the reference specifies data that is also immutable.

Inside data

Inside data is the realm of SQL and SQL’s DDL. SQL and DDL live in the “now”…

Like other operations in SQL, updates to the schema via DDL occur under the protection of a transaction and are atomically applied. These schema changes may make significant difference in the ways that data stored within the database is interpreted. It is an essential quality of DDL that transactions that precede a DDL operation are based on the schema that existed before and transactions that follow the DDL operation are based on the schema as changed by the operation. In other words, changes to the schema participate in the serializable semantics of the database.

Data arriving from the outside may be processed into a form easier for the a service to use. One option is to keep this external data in some kind of document form. The example in the paper is XML, the language of choice circa 2005. Importantly this supports extensibility whereby information can be added that was not declared in the original schema for the message.

Extensibility is in many ways like scribbling on the margins of a paper form. It frequently gets the desired results, but there are no guarantees.

Another option is to “shred” the data – converting it into a relational representation.

It is interesting that extensibility fights shredding. It is had to map unplanned extensions to planned tables.

Choosing an appropriate data representation

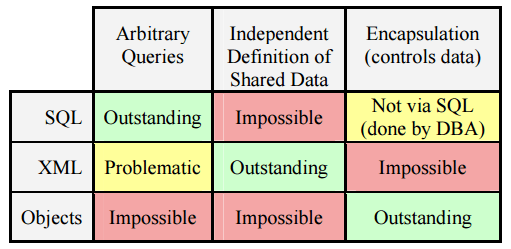

The paper closes by examining three different representations of data – XML, SQL, and object encapsulation. (We could add / substitute json today). SQL and XML/json are essentially anti-encapsulation making data fully accessible. Components and objects emphasize encapsulation.

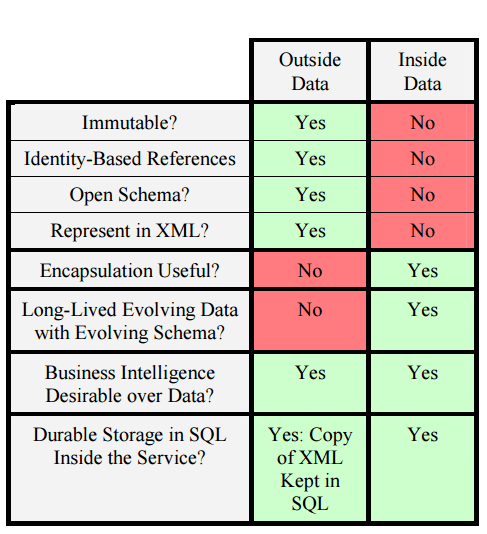

Taking what we’ve learned so far, Helland shares the following table of requirements for inside data and outside data:

… We consider encapsulation and realize that outside data is not protected by code. There is no formalized notion of ensuring that access to the data is mediated by a body of code. Rather, there is a design point that if you have access to the raw contents of a message, you should be able to understand it. Inside data is always encapsulated by the service and its application logic.

Each of the three representations has different strengths and weaknesses, that make them better or worse suited to the inside and outside roles:

Each model’s strength is simultaneously its weakness! What makes SQL exceptional for querying makes it dreadful for independent definition of shared data. XML is wonderful for the independent definition and creation of data but is anti-encapsulated. Encapsulation is the key to the success of object systems and yet it prevents querying. You cannot try harder to add features to one of these models to address the weaknesses without undermining its strengths!

Thus we conclude that there is a role (and a need) for all three:

This conclusion should not surprise us when we realize that most application developers are pretty smart. It is common practice today to use XML to represent data on the outside, objects to implement the business logic of the services, and SQL to store the data on the inside. We simply need all three of these representations and we need to use them in a fashion that plays to their respective strengths!

Excellent article!