FarmBeats: An IoT platform for data-driven agriculture Vasisht et al., NSDI ’17

Today we have another pragmatic, low cost, IoT system case study. And it’s addressing a problem almost as important as cricket: how can we help to meet the burgeoning demand for food across the globe by increasing farm productivity? [Just in case British humour doesn’t translate to all cultures reading this post, yes, that’s a joke!].

… field trials have shown that techniques that use sensor measurements to vary water input across the farm at a fine granularity (precision irrigation) can increase farm productivity by as much as 45% while reducing the water intake by 35%. Similar techniques to vary other farm inputs like seeds, soil nutrients, etc. have proven to be beneficial.

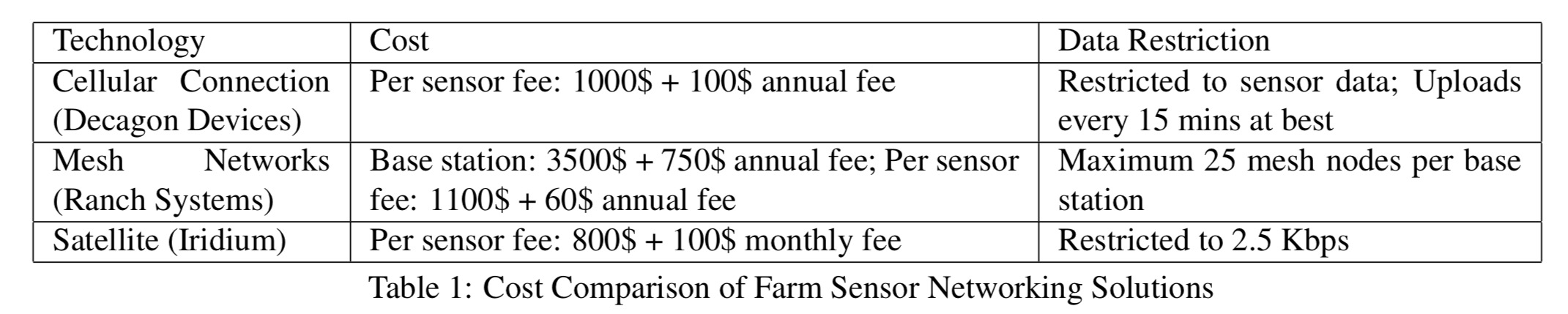

Given that, why isn’t everyone doing it? Manual sensor data collection is expensive and time-consuming, but automated sensor data collection typically requires expensive cellular data loggers and accompanying subscriptions – and even then the limited data rates don’t let you upload all the data you’d really like to. Cellular coverage can also be poor on farms, and prone to weather-based outages.

What if we could use wifi out on the farm?

Ingredients for a smart farm

- A collection of sensors for e.g., soil temperature, pH, and moisture. Also, some IP cameras may be useful to keep a remote eye on things.

- For sensors without wifi support, some Arduinos, Particle Photons ($20 each), or NodeMCUs to add wifi capability.

- Some weatherproof boxes to enclose the sensors

- Some IoT base stations providing wifi across the farm – these are connected to the farmer’s home internet connection using an unlicensed TV White Spaces (TVWS) network using FCC certified Adaptrum ACRS 2 radios ($200 each).

- A solar charging system to power the base station, comprising two 60 Watt solar panels connected to a solar charge controller and backed by four batteries.

- An 8-port digital logger PoE switch through which the solar power is routed, giving the ability to turn individual base station components on or off.

- A Raspberry Pi with a 64GB SD card to serve as the base station controller

- An IoT gateway device in the farmer’s home – basically a laptop.

- A drone for capturing imagery (e.g., DJI Phantom 2, Phantom 3, or Inspire 1).

- A cloud platform for long-term storage and analytics – in this instance the Azure IoT suite was used.

The cost per sensor using this network approach is an order of magnitude less than existing systems.

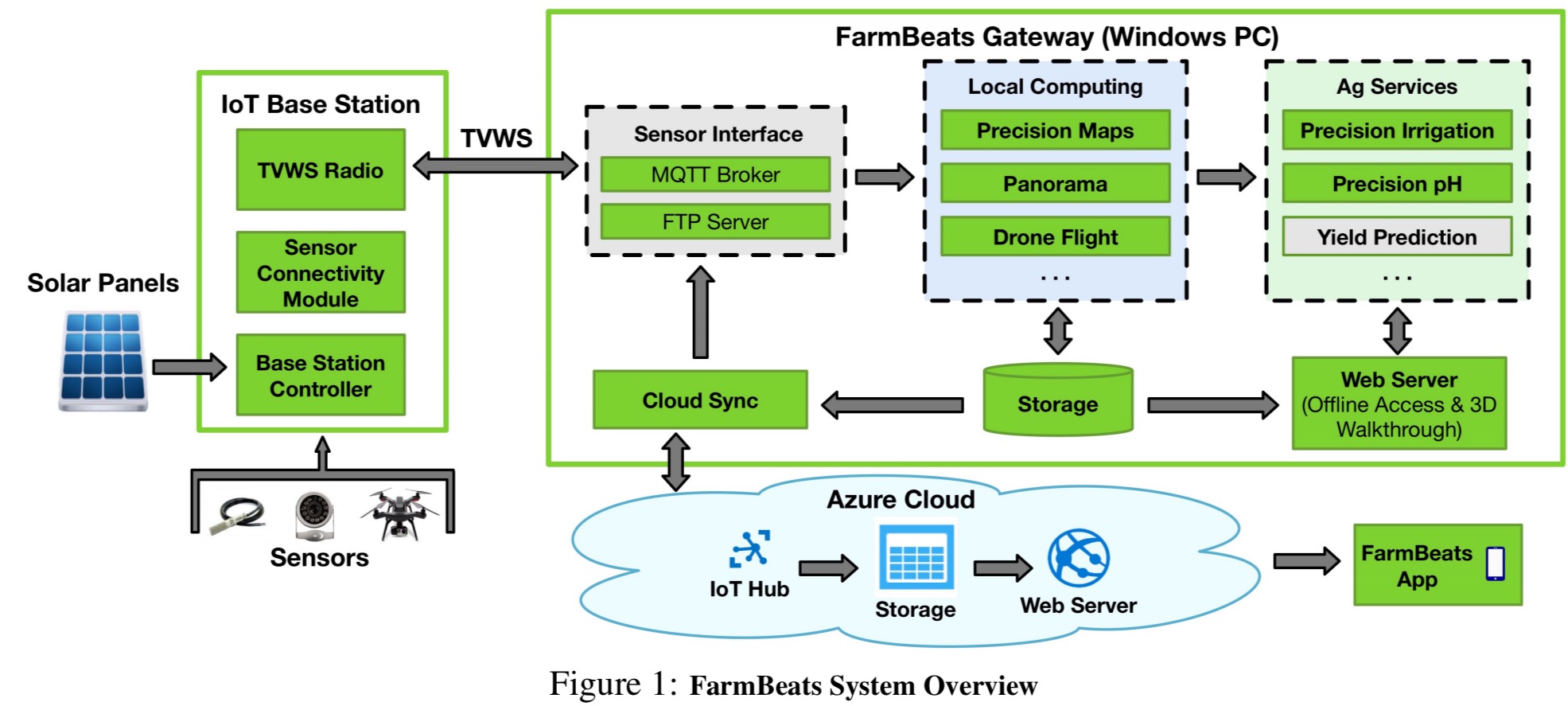

Having assembled all of the ingredients, connect them together like this:

Connectivity

FarmBeats leverages recent work in unlicensed TV White Spaces (TVWS) to setup a high bandwidth link from the farmer’s home Internet connection to an IoT base station on the farm. Sensors, cameras, and drones can connect to this base station over a Wi-Fi front-end. This ensures high bandwidth connectivity within the farm.

The farm itself may not have great Internet connectivity though. Even at the best of times uploading high bandwidth drone videos may be challenging, on top of which farms are prone to weather-related network outages that may last for weeks. The solution to both challenges is a gateway device installed at the farmer’s home which can provide continuous operation for the farm network even when the uplink to the Internet is down. The gateway also performs significant local computation on raw farm data before uploading it to the cloud. The farmer can access detailed data about the farm via the gateway whenever he or she is on the farm network.

Power

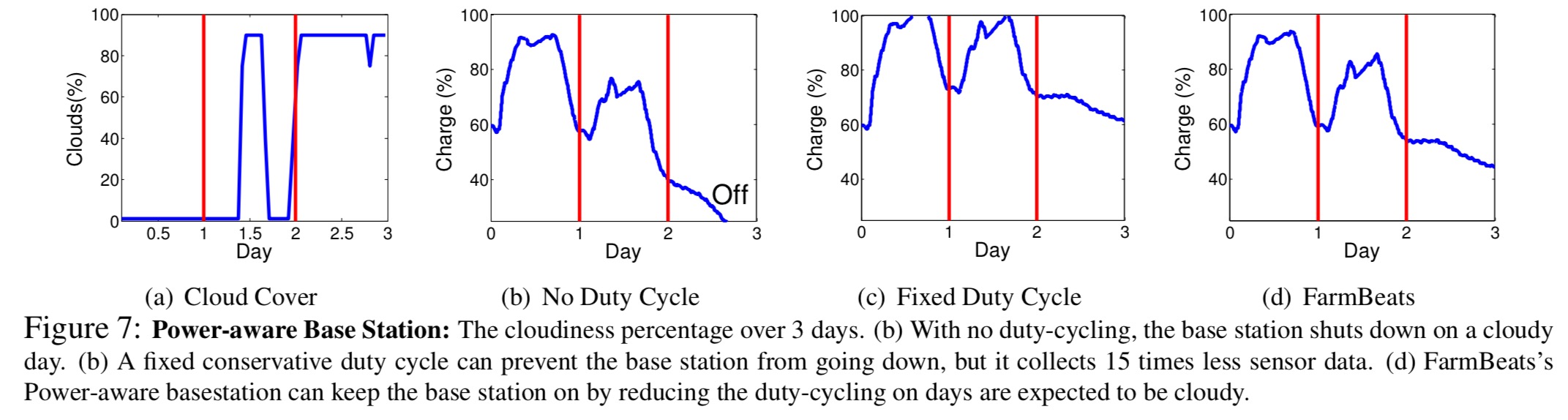

The IoT base station on the farm is powered by solar panels with battery back-up. The base station controller caches sensor data collected from the sensors and syncs it with with IoT gateway when the TVWS device is switched on. It also plans and enforces duty cycle rates depending on the current battery status and weather conditions.

The solar power output varies with the time of day and weather conditions, and the goal within a given planning period (1 day) is to consume at most the amount of power that can be harvested from the solar panels. This is not enough to power the TVWS device continually (it uses 5x the power of the base station). Duty cycle planning figures out a power budget based on estimates of the solar panel output given the weather conditions (forecasts from the OpenWeather API). This power has to be used to collect data from sensors, upload the data to the gateway over the TVWS link, and support farmers using the base station for internet connectivity via their smart phones while on the farm (this is a variable component of the power budget).

FarmBeat’s duty cycling algorithm aims to minimise the length of the largest data gaps, under the constraints of energy neutrality and variable access.

A greedy algorithm is used to determine which data to upload to the gateway when the TVWS device is powered on, and the schedule is set such that the TVWS device is not powered on when there is no data to be uploaded. The base station is also duty cycled so that it can connect to the sensors frequently enough to capture their data. The sensors themselves consume very little power compared to the base station, and are set with a duty cycle off time less than the base station transfer windows.

The following charts show the impact of power-aware duty cycling:

Imaging and bandwidth management

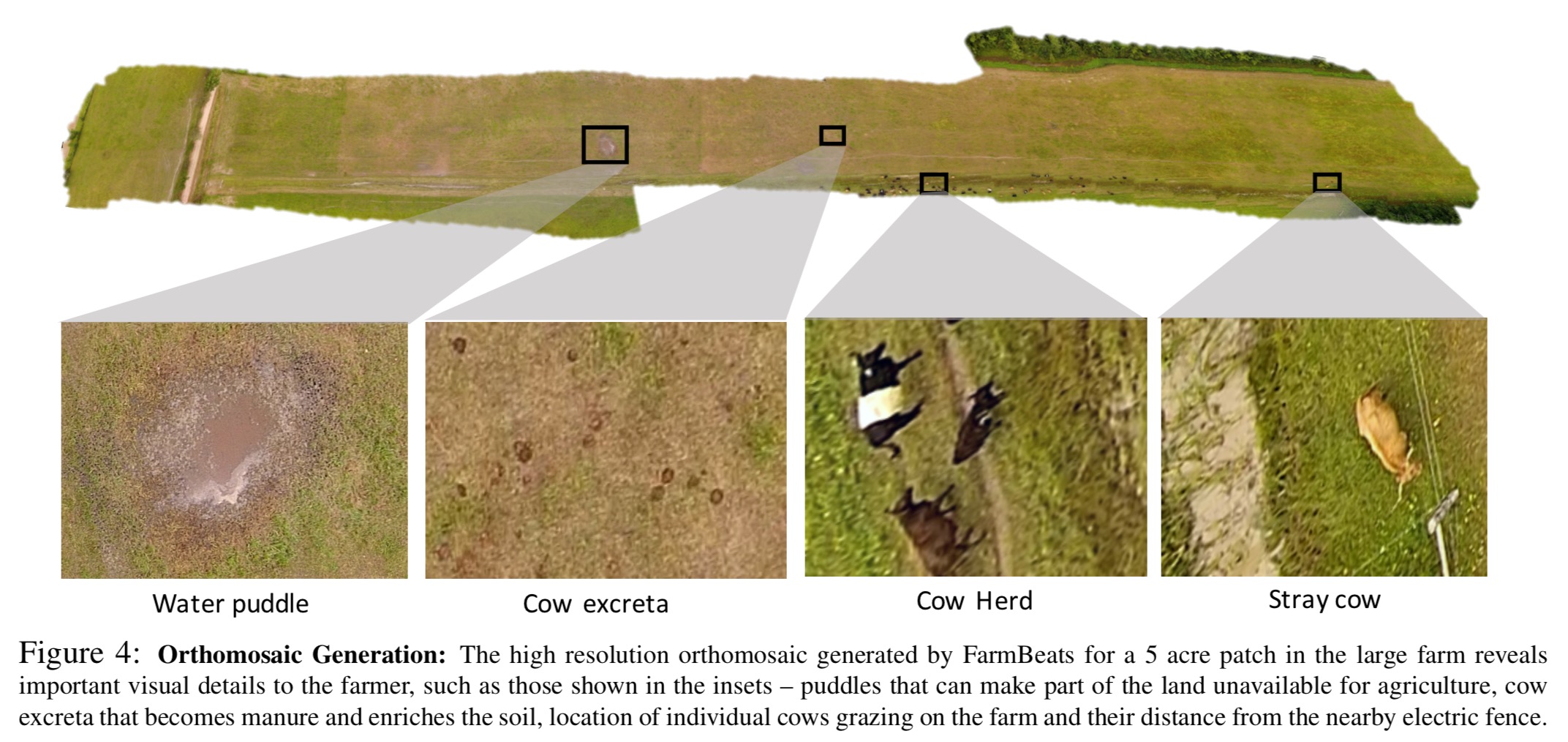

Aerial photography from drones is an important part of data gathering. A flight path must be planned for a drone to cover the farm in as efficient a manner as possible, and then the resulting photos must be stitched together into an orthomosaic.

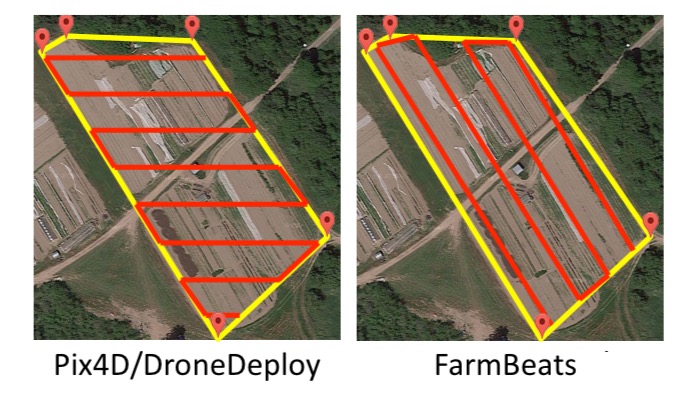

To cover as much of the farm as possible in as little time as possible, the most efficient plan is to minimise the number of waypoints in the flight path since at each waypoint the drone decelerates and comes to a halt before accelerating again. Most existing commercial flight planning systems use an east-west flight path. FarmBeats instead calculates the convex hull of the area to be covered and creates a flight path that minimises waypoints. This reduced the time taken to cover an area by 26% in the FarmBeats trial deployments.

FarmBeats further saves on flight time (and hence power requirements) by taking advantage of the wind.

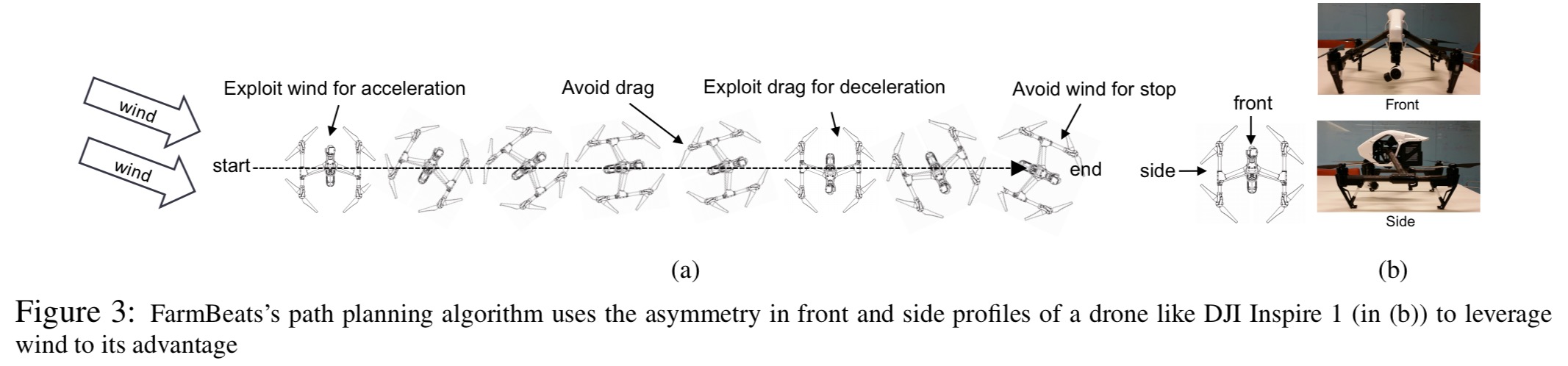

Since farms are large open spaces and typically very windy, we observed that quadrotors that have an asymmetric physical profile can exploit the wind either for more efficient propulsion of deceleration. Figure 3 (below) shows an example of a quad rotor (DJI Inspire 1) that has an asymmetrical profile, where its front and side are considerably different; thus, it can exploit the wind similar to sailboats.

The angle of the quadrotor with respect to the vertical axis is called yaw. During acceleration with a favourable wind behind, the longer side is turned to face the wind to benefit from wind assistance. Once at speed, the narrower side is turned to the wind to reduce air drag. Deceleration into can once again exploit air drag (and/or a headwind). Depending on wind velocity, this adaptive wind-assisted yaw control algorithm reduced flight time by up to 5%.

A 4-minute flight capturing 1080p video at 30 frames per second is almost a gigabyte of video data. Existing solutions ship the video to the cloud and create an orthomosaic there, but FarmBeats incorporates the orthomosaic video processing pipeline into the gateway to do as much processing locally as possible. This is challenging since the computation of high-resolution surface maps is both compute and memory intensive and not suitable for the farm gateway device.

We have developed a hybrid technique which combines key components from both 3D mapping and image stitching methods. On a high level, we use techniques from the aerial 3D mapping systems, just to estimate the relative position of different video frames; without computing the expensive high resolution digital surface maps. Since this process can be performed at a much lower resolution, this allows us to get rid of the harsh compute and memory requirements, while removing the inaccuracies due to non- planar nature of the farm. Once these relative positions have been computed, we can then use standard stitching software (like Microsoft ICE) to stitch together these images.

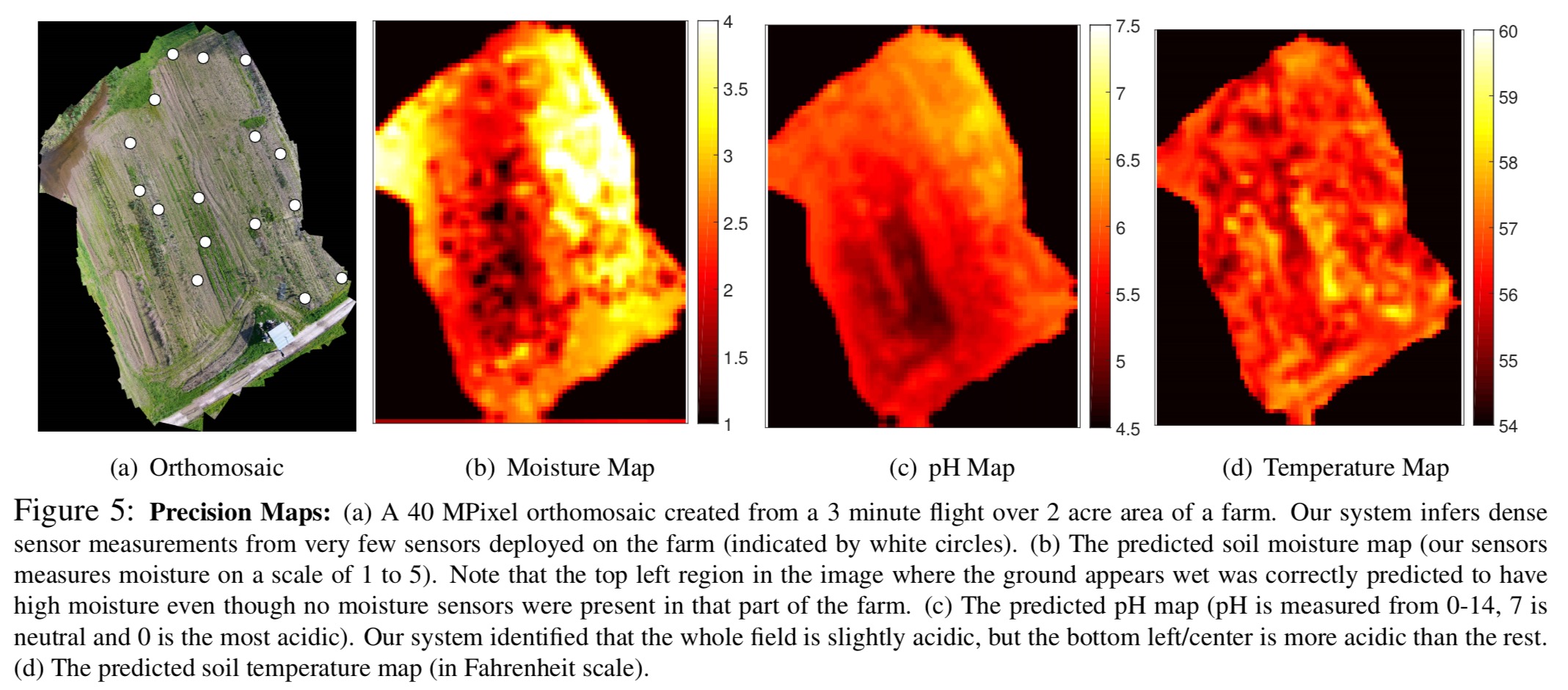

Given the orthomosaic and the sensor readings, the final challenge is to create a precision agriculture maps for the whole farm. For example, moisture maps, pH maps, and temperature maps.

A machine learning model based on probabilistic graphical models that embed Guassian processes is used to extrapolate from the sensor data points to the full territory. This model seeks to balance spatial and visual smoothness:

- Since we are measuring physical properties of the soil and the environment, the sensor readings for locations that are nearby should be similar (spatial smoothness).

- Areas that look similar should have similar sensor values. For example, a recently irrigated area has more moisture and hence looks darker (visual smoothness).

FarmBeats deployments have been running at two different farms for over six months, connecting to around 10 different sensor types, three different camera types, three different drone versions, and the farmers’ phones. The farmers use it for precision agriculture, animal monitoring, and storage monitoring.