Application crash consistency and performance with CCFS Pillai et al., FAST 2017

I know I tend to get over-excited about some of the research I cover, but this is truly a fabulous piece of work. We looked “All file systems are not created equal” in a previous edition of The Morning Paper, which showed that the re-ordering and weak atomicity guarantees of modern filesystems cause havoc with crash recovery in applications. For anyone building an application on top of a file system, “All file systems are not created equal” is on my required reading list. Today’s paper is the follow-up, which looks at what we can do about the problem. CCFS (the Crash-Consistent File System) is an extension to ext4 that restores ordering and weak atomicity guarantees for applications, while at the same time delivering much improved performance. That’s not supposed to happen! Normally when we give stronger consistency guarantees performance degrades. The short version of the story is that ccfs introduces a form of causal consistency in which file system operations are grouped into streams. Within a stream ordering is preserved, across streams by default it is not (some important details here we’ll cover later on). In the simplest mapping, each application is given its own stream.

I’m going to reverse the normal order of things and start with some of the evaluation results, then we’ll take a step back and see how ccfs pulls them off. Before we do that, just one other small observation – ccfs ends up being just 4,500 lines of changed/added code in the 50Kloc ext4 codebase. Which just goes to reinforce the point that it’s not the amount of code you can churn out that counts, it’s the careful design and analysis that goes into figuring out what code to write in the first place (and that often leads to there being less of it as well).

The situation addressed by ccfs is related to, but different from, the corruption and file system crash problems that we looked at last week. Here we assume a system crash, and the file system is behaving ‘correctly’ – just not as the application designer expected. On the former front, many thanks to @drsm79 and @danfairs who pointed me to some fabulous data from CERN on the prevalence of file system corruptions in the wild (about 6/day on average that are observed!). Steve Loughran’s talk on “Do you really want that data?” might also be of interest.

CCFS results

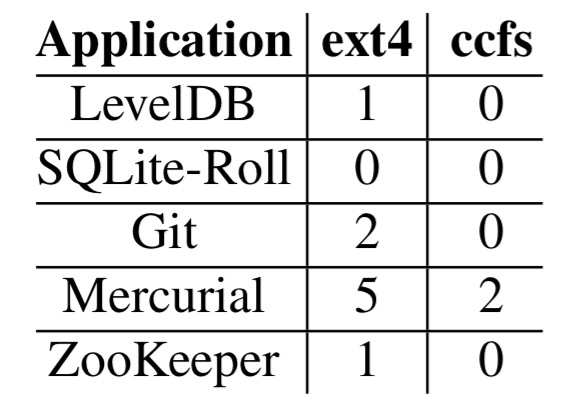

So let’s start out with a reminder of the current situation, and then compare it against ccfs. Using Alice and BoB (the testing tools from “All file systems are not created equal”), the authors test LevelDB, SQLite, Git, Mercurial, and ZooKeeper. Alice records the system call trace for an application workload, and then reproduces the possible set of file system states that can occur if there is a system crash.

Here are the Alice results:

Ext4 results in multiple inconsistencies: LevelDB fails to maintain the order in which key-value pairs are inserted, Git and Mercurial can result in repository corruption, and ZooKeeper may become unavailable. With ccfs, the only inconsistencies were with Mercurial. These inconsistencies are exposed on a process crash with any file system, and therefore also occur during system crashes in ccfs.

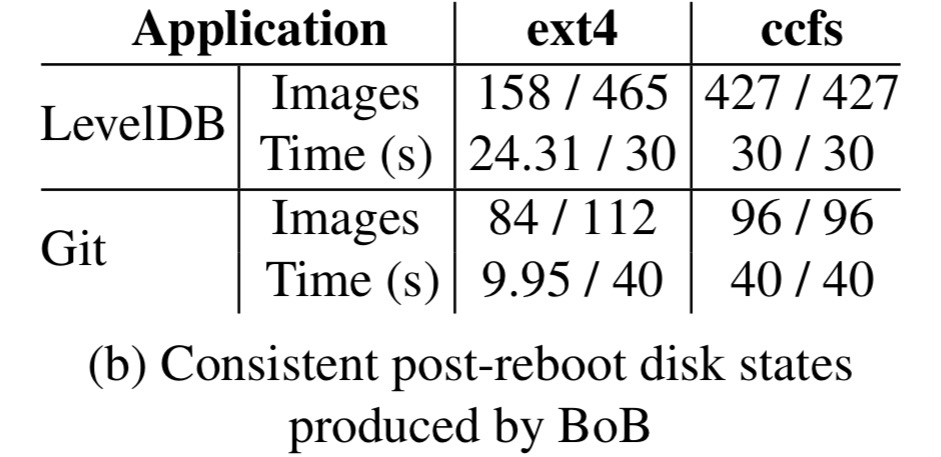

BoB is the ‘block order breaker’ – it records the block-level trace for an application workload and reproduces the set of disk images possible if a crash occurs.

We used Git and LevelDB to test our implementation and compare it with ext4; both have crash vulnerabilities exposed easily on a re-ordering file system… LevelDB on ext4 is consistent on only 158 of the 465 images reproduced; a system crash can result in being unable to open the datastore after reboot, or violate the order in which users inserted key-value pairs. Git will not recover properly on ext4 if a crash happens during 30.05 seconds of the 40 second runtime of the workload. With ccfs, we were unable to reproduce any disk state in which LevelDB or Git are inconsistent.

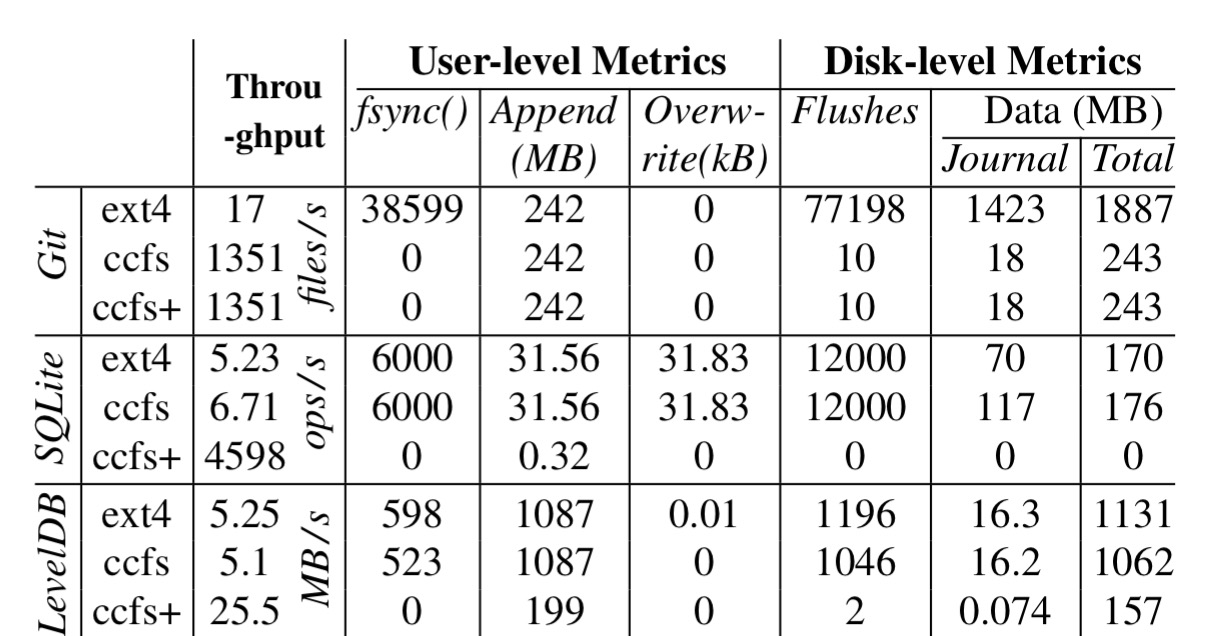

So ccfs clearly improves application consistency – but does it harm performance to do so? The evaluation first studies each of Git, LevelDB, andSQLite in isolation, then later on looks at mixed workload results. Single application results are shown below. The ccfs rows show what happens when the application is run as is on ccfs, ccfs+ represents a minimal change to the application to remove fsync calls not needed with ccfs.

For the Git workload, ccfs is 80x faster, for the SQLite workload it is 685x faster, and for LevelDB it is 5x faster. Not bad eh?

Achieving correctness atop ccfs (while maintaining performance) required negligible developer overhead: we added one

setstream()call to the beginning of each application, without examining the applications any further.

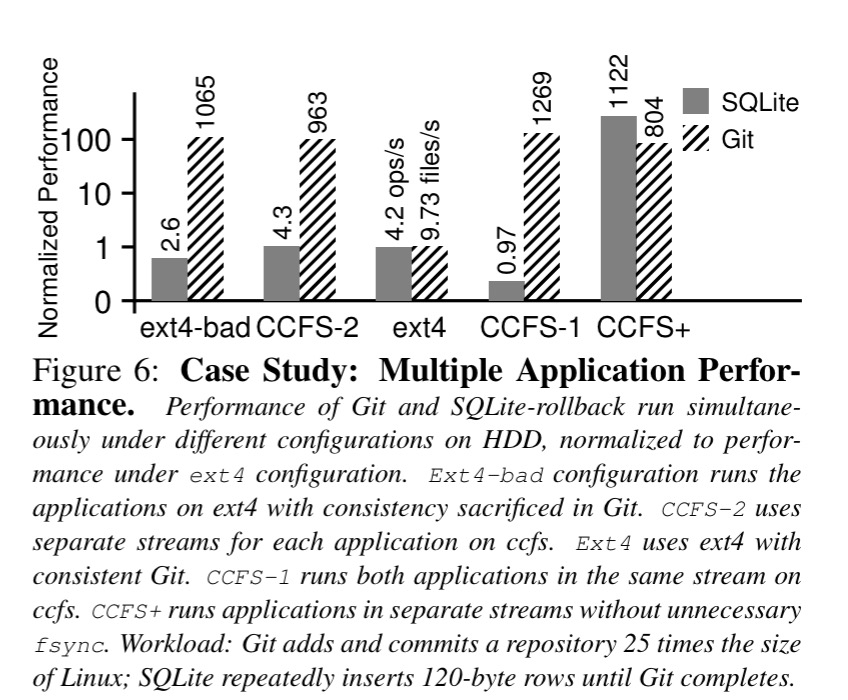

Here’s what happens when you run a multiple application workload (each application with its own stream).

.

.

Once more, in the ccfs+ case, we’re looking at almost 100x!

Now that you’re sufficiently motivated to dive into the details of how this feat is possible, let’s take a step back and look at the root causes of crash inconsistencies and poor performance to set the scene.

The problem

Many applications use a specialized write protocol to maintain crash consistency of their persistent data structures. The protocols, by design or accident, frequently require all writes to commit in their issued order.

The problem is, with modern file systems, they don’t. Constraining ordering leads to performance costs, and so ‘many file systems (including ext4, xfs, btrfs and the 4.4 BSD fast file system) re-order application writes, and some file systems commit directory operations out of order (e.g., btrfs). Lower levels of the storage stack also re-order aggressively, to reduce seeks and obtain grouping benefits.”

The hypothesis leading to ccfs (and that seems to be borne out by the results) is that application code is depending on two specific file system guarantees that aren’t actually guaranteed:

- The effect of system calls should be persisted on disk in the order they were issued by applications, and a system crash should not produce a state where system calls appear re-ordered.

- Weak atomicity guarantees when operating on directories, and when extending the size of file during appends. (I.e., both things happen or neither of them happen).

Among 60 vulnerabilities found in “All file systems are not created equal,” 50 are addressed by maintaining order and weak atomicity, and the remaining 10 have minor consequences that are readily masked or fixed. The amount of re-ordering done in modern file systems seems to increase with every release, so the problem in the wild is only getting worse.

Ordering is bad for file system performance because it requires coordination, and because it prevents write avoidance optimisations (writes that actually never need to be written to disk because of future truncates or overwrites). Conversely, when fsync calls or cache eviction force writes, it is called write dependence.

Apart from removing the chance for write avoidance, write dependence also worsens application performance in surprising ways. For example, the

fsync(f2)call becomes a high-latency operation, as it must wait for all previous writes to commit, not just the writes to f2. The overheads associated with write dependence can be further exacerbated by various optimizations found in modern file systems. For example, the ext4 file system uses a technique known as delayed allocation, wherein it batches together multiple file writes and then subsequently allocates blocks to files. This important optimization is defeated by forced write ordering.

Streams in CCFS

Ccfs says that with proper care in the design and implementation, an ordered and weakly atomic file system can be as efficient (or better, as we saw!) as a file system that does not provide these properties.

The key idea in ccfs is to separate each application into a stream, and maintain order only within each stream; writes from different streams are re-ordered for performance. This idea has two challenges: metadata structures and the journaling mechanism need to be separated between streams, and order needs to be maintained within each stream efficiently.

There is a simple setstream API which allows an application developer to further subdivide applications writes into multiple streams should they so wish.

Ccfs is based on ext4, which maintains an in-memory data structure for the running transaction. Periodically this transaction is committed, and when the committing process starts a new running transaction is created. Ext4 therefore always has one running transaction, and at most one committing transaction. In contrast, ccfs has one running transaction per stream. When a synchronization system call (e.g. fsync) is made, only the the corresponding stream’s transaction is committed. This is part of the secret to ccfs’ performance gains.

So far then we’ve talked about a model whereby causality is assumed for writes from a single application (stream), and these writes are preserved in order. There are no ordering guarantees for writes across streams though. But this isn’t quite right… suppose application A downloads a file, then application B updates it – this is an example where causality matters across streams.

The current version of ccfs considers the following operations as logically related: modifying the same regular file, explicitly modifying the same inode attributes (such as the owner attribute), updating (creating, deleting or modifying) directory entries of the same name within a directory, and creating a directory and any directory entries within that directory.

These logically related operations across streams are tracked. If the stream that performed the first operation commits before the second operation happens, all is well. Otherwise when a cross-stream dependency on an uncommitted updated is detected ccfs temporarily merges the streams together and treats them as one until commit.

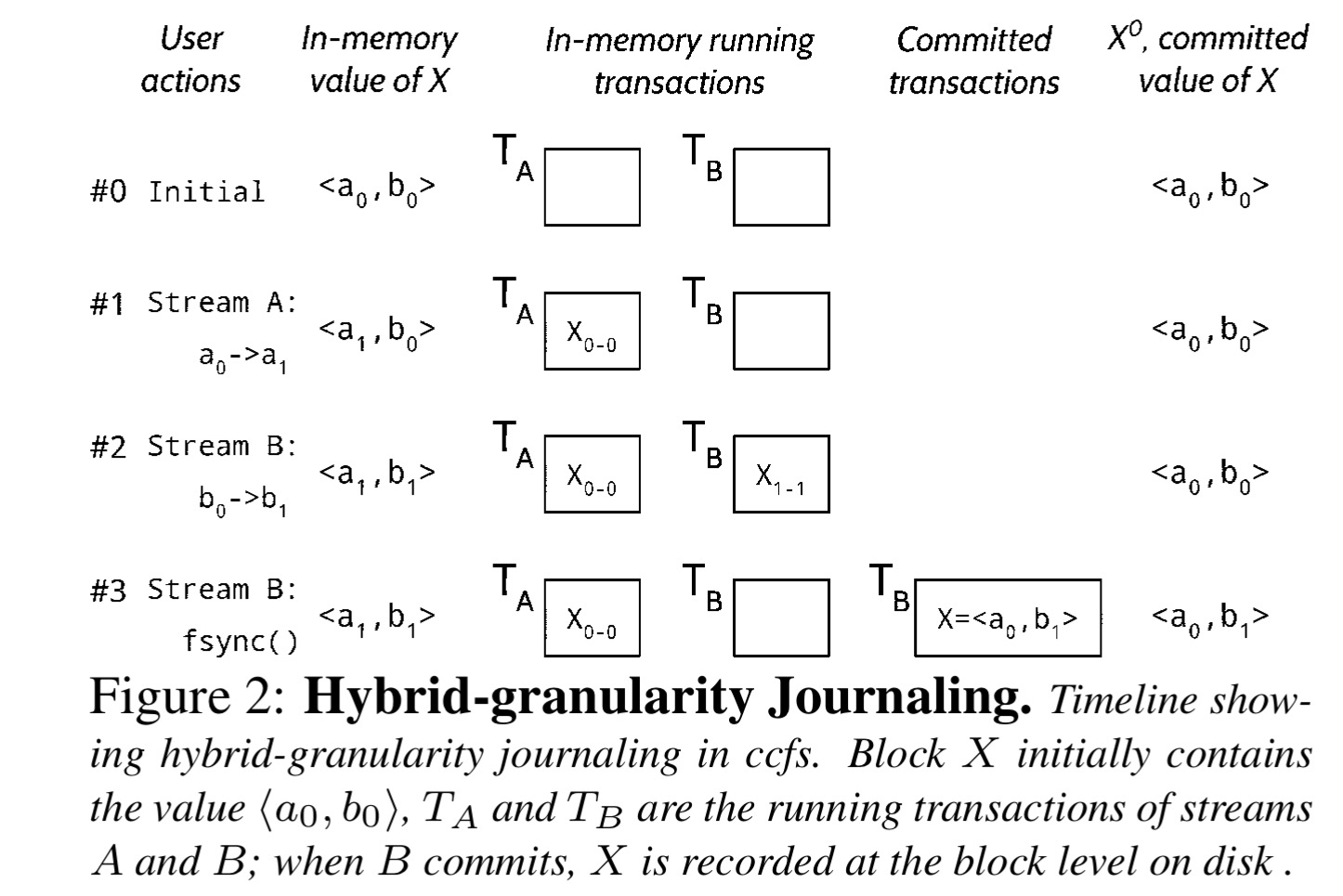

To support these stream-based operations, ccfs extends ext4’s block-granularity journaling of file system metadata with an additional level of byte granularity journaling (since different streams might exist in the same block). The result is described as hybrid-granularity journaling. By allowing streams to be separated in this way the delayed-logging optimisation of ext4 is unaffected. Commits and checkpoints are block-granular which preserves delayed checkpointing. Say streams A and B are both active in a block, and B wants to commit while A is still running – what will be written to the disk is just the initial content of the block, with B’s changes super-imposed.

Hybrid-granularity journaling works for independent metadata changes within the same block, but also need to consider the case of multiple concurrent updates to the same file system metadata structure. For this ccfs using delta journaling which works by storing command logs (add 1, subtract 5 etc.) instead of changed values. So long as the operations are commutative this gives the needed flexibility.

To finish up, we still have the question of how ccfs maintains order within a stream. Ext4 uses metadata-only journaling and can re-order file appends and overwrites. Added data journaling in addition preserves application order for both metadata and file data – but it is slow because data is often written twice. To address this ccfs using a technique called selective data journaling that preserves the order of both data and metadata by journalling only overwritten file data.

Since modern workloads are mostly composed of appends, SDJ is significantly more efficient than journaling all updates.

On its own, SDJ would disable a meaningful optimisation called delayed allocation (see section 3.4), ccfs restores this ability using an order-preserving delayed allocation scheme.