PharmaLeaks: Understanding the business of online pharmaceutical affiliate programs – McCoy et al., USENIX Security, 2012

Yesterday we looked at the technology infrastructure supporting spam-based advertising businesses. Today’s paper gives a fascinating look at the business model. How this is possible is itself a very interesting story which we’ll get to shortly. The authors gained access to four years of transaction logs for three pharmaceutical affiliate programs, covering over $185 million in sales. What’s the Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) for internet-advertised online pharmaceuticals? What about the Lifetime Value (LTV) of a customer – do people really buy more than once??? What kinds of transaction volumes, revenues, and gross margins are we talking about?

This is an unusual research paper. We introduce no new artifact, we develop no new inference technique, we deploy no new measurement infrastructure. We do none of these things because we don’t need to; we have the actual data sets that we would otherwise try to measure, infer, or estimate…

GlavMed and RX-Promotion are long-operating pharmaceutical affiliate programs based in Russia. They fell out, and ultimately resorted to DDoSing and hacking each other. “Perhaps inspired by the ‘online leak’ meme popularized by Wikileaks and others,” they made information about each others operations (obtained via hacking) available online. GlavMed and SpamIt are sister programs run by the same organization, and both use the same database schema. SpamIt was ‘forked’ from the GlavMed database on June 19, 2007. “Leaked chat logs of the program operators suggest that this split was related to the owner’s contemporaneous acquisition of spamdot.biz, a popular closed spammer forum of that period.”

GlavMed and RX-Promotion are open affiliate programs, and as such they actively advertise and recruit new affiliates to join their programs (with the public advertising focused on SEO-based advertising vectors). SpamIt, on the other hand, is a closed program – focused specifically on email spam – where affiliates join by invitation.

Table 1 below summarises the affiliate program data that was leaked and used in the paper analysis:

Industry background

The rise of the affiliate program, or “partnerka” model has separated advertisers, who are paid on commission to attract customer traffic, from sponsors who handle the back-end.

This evolution is not unique to abusive advertising; indeed, large legitimate merchants such as Amazon also sponsor affiliate programs as a means of advertising. However, it has been deeply internalized within the underground ecosystem including the pay-per-install, FakeAV, pornography, pharmaceuticals, herbal supplements, replica, and counterfeit software markets, among others.

Commissions for advertisers are on the order of 30-40% of gross revenue, typically paid via a quasi-anonymous online money transfer service such as WebMoney or LibertyReserve.

Advertisers benefit from focus and mobility – they don’t need to worry about the back end and can focus all their energies on driving customer traffic. “Indeed, this functional specialization has supported the creation of ever more sophisticated botnets for email delivery or ‘black hat’ search engine optimization, and many of the largest botnets are directly involved in advertising the programs in this paper.” The mobility advantage is that advertisers can easily switch back-end programs at will, which gives them strong bargaining power with the affiliate programs.

The sponsoring affiliates free themselves from direct exposure to the criminal risks associated with large-scale advertising enterprises via mass compromise of computers and on-line accounts. By paying on a commission basis, they also outsource “innovation risk.”

The online pharmaceutical market supports tens of affiliate programs, thousands of affiliates (independent advertisers), and hundreds of thousands of customers.

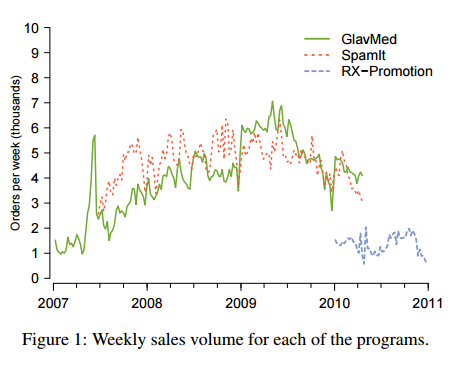

Order volumes and average order size

During the measurement period, 584,199 unique customers placed orders via GlavMed, 535,365 via SpamIt, and 59,769-69,446 distinct customers placed orders via RX-Promotion (the data for RX-Promotion covers a shorter time period).

The average successful order size is between $115 and $135.

Who are the customers?

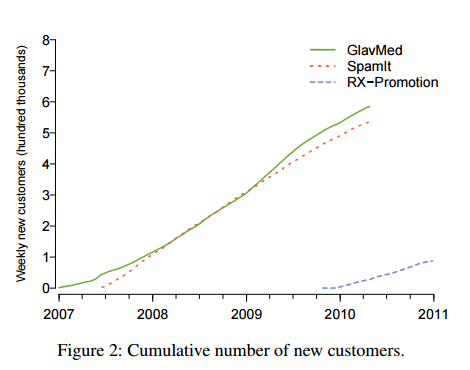

The affiliate programs have a steady flow of both new and repeat business. The authors plotted the cumulative number of unique customers seen in each program per week over the measurement period. Changes in slope therefore indicate changes in the rate of new customer acquisition.

From these trends it is clear that the affiliate programs are attracting new customers at a steady rate over time, and that the market does not appear to be saturating.

Repeat orders are are important part of the business, constituting 27% and 38% of the business for GlavMed and SpamIt respectively. RX-Promotion repeat order revenue is between 9 and 23% of overall revenue.

This data highlights a counterpoint to the conventional wisdom that online pharmacies are pure scams: simply taking credit cards and either never providing goods or providing goods of no quality. Were this hypothesis true, we would not expect to see repeat purchases—clear signs of customer satisfaction—in such numbers. Anecdotally, we have placed several hundred such orders ourselves and, while we cannot speak to the quality of the products we received, we have almost always received a product in return for our payment.

What do they buy and why?

What do customers buy?

For GlavMed and SpamIt, the jokes about spam are spot on: “erectile dysfunction” (ED) purchases dominate their revenue. Customers do purchase other notable drugs, but they represent a small fraction of revenue over time for these programs.

Order volume and program revenue for different groups of drugs are summarized below.

The hypothesis is that lifestyle drugs in the ED and related category, which are relatively easy to obtain under prescription, are bought online for reasons of embarrassment or price. Drugs with abuse potential includes addictive drugs, and this addiction is presumed to drive purchases. These drugs are over-represented in repeat orders. The final group of drugs, those for treating chronic conditions, neither carry an abuse risk nor represent a clear cause for social discomfort – here the authors presume the purchase is motivated by economics; lower direct drug costs and the absence of indirect costs, e.g. a doctor’s visit.

Men by the way have a peak purchase of male baldness products between ages 20-30, and male enhancement products between 45-50.

How much money are the affiliates making?

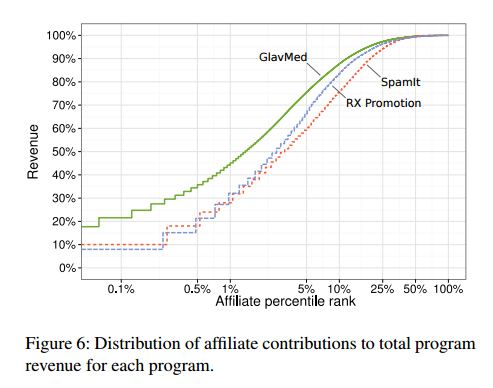

Affiliates seem to follow a power law. The CDF of affiliate contributions to total program revenue for the three programs is shown below:

This graph shows that just 10% of the highest-revenue affiliates account for 75-90% of total program revenue across the three affiliate programs; for GlavMed and RX-Promotion in particular, the remaining 90% of affiliates bring in just 10-15% of total revenue… Moreover, there is evidence that these high-revenue affiliates are not simply lucky, but represent the best-established and experienced advertisers.

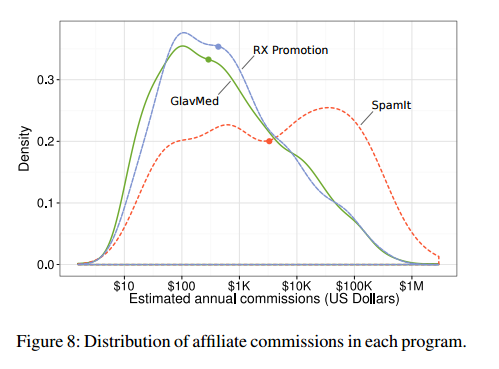

Because of this structure, many affiliates earn small commissions. The median annualized affiliate commissions for GlavMed, SpamIt, and RX-Promotion are $292, $3,320, and $428 respectively. The top five affiliates meanwhile, were each able to earn over $1M in a twelve-month period.

Figure 8 below shows the distribution of annualized commissions across all affiliates.

The affiliate programs themselves make an average weekly revenue per affiliate of between $2000-$7000. The closed SpamIt program is much more effective at attracting productive affiliates and avoiding unproductive ones.

Focusing only on these most productive affiliates, we would intuitively expect them to also be the operators of the largest spamming botnets. However, even a cursory examination of the data shows that there is considerable more complexity at work. For example, while the operators of the prodigious Rustock botnet (cosma2k, bird, and adv1) indeed receive large commission payments (over $1.9M), botnet operators do not appear to dominate the top earners. Indeed, two of the largest botnet operators, docent (operator of MegaD) and severa (operator of Storm and Waledac) only received modest payments of $308K and $169K, respectively, for directly advertising SpamIt sites.

The second most profitable affiliate, scorrp2, earned close to $3M while advertising domains emerging from a range of botnets.

Gross margins in the affiliate program business seem to be pretty low, between 22.9% and 36.9%.

After commissions, supply costs for the programs are one of the largest expenses. Using the categories from Figure 2, ED contains by far the most popular products purchased, and also has the highest markups of more than

15 to 20 times the supply cost. The average markup of Viagra in GlavMed and SpamIt, for instance, translates to a customer price 25 times cost. Markups in the Abuse and Chronic categories are considerably smaller, ranging between 5–8 times supply cost.

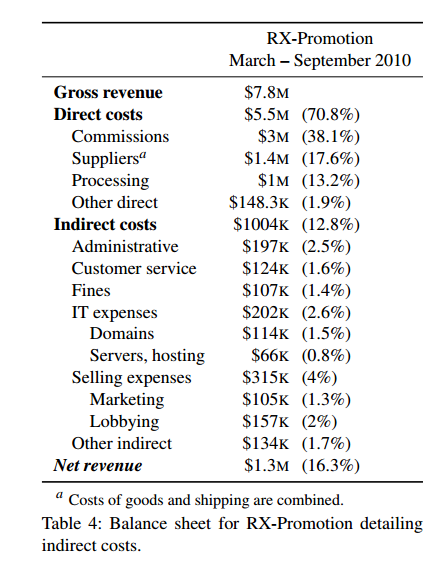

Factoring in indirect costs (i.e. those costs not generally attributable to individual sales) we see that the on gross revenue of $7.8M between March and September 2010, RX-Promotion made a net profit of $1.3M.

We believe that 10-20% is likely to reflect a typical net revenue for successful pharmaceutical programs.

A note on payment processing…

Previously, our group identified that a small number of banks were critical to virtually all online pharmaceutical sales. However, the means by which those

banks were accessed has never been well documented. In fact, in the “high-risk” payment market, merchant processing is frequently handled by independent Payment Service Providers (PSPs) who manage the relationships with acquiring banks and provide Web-based payment gateway services to clients.

Amongst these payment service providers, the data shows a clear dominance of Visa processing.

Visa transactions represent almost 67% of all revenue, followed by MasterCard with 23% and American Express with 6% (with the remainder concentrated in eCheck transactions through the ACH system). While part of this discrepancy is likely due to demand—Visa is the most popular payment card brand—this difference also reflects a supply issue as well. For reasons not entirely clear, it has traditionally been far easier for online pharmaceutical programs to obtain payment processing services for Visa than for MasterCard or Amex.